By SUSAN HARLAN

Brooklyn, New York, US

This July and August, I stayed at my friend Sarah’s apartment in Brooklyn while she and her family were in Vermont. The original plan was that I would cat-sit their black cat Buster, but they had a mouse problem at their Vermont place, so after ten days or so, they drove back into the city to reclaim Buster and put him to work.

The apartment was on 56th Street between 4th and 5th Avenues, not far from Green-Wood Cemetery, where I liked to take walks. Most days, I went to the Sunset Park pool in the late morning and then to the New York Public Library. The N train runs across the Manhattan Bridge, offering a view of the Brooklyn Bridge and, further off in the distance, the Statue of Liberty.

But I could also see the Statue of Liberty from another vantage point. In the evenings, when it wasn’t too hot, I took my dog Millie for walks out to the Brooklyn Army Terminal. We walked under the BQE, past laundromats, auto body shops, and NYU Lutheran Medical Center, past stone and furniture warehouses, and around a brick smoke stack, out to the water.

I knew of the Army Terminal, but I had never seen it before. It is a utilitarian castle. Completed in 1919, this four million square-foot structure was the largest military supply base in the U.S. through World War II, with over 20,000 military and civilian personnel. The terminal was constructed of girder-less, steel reinforced concrete slabs, and three bridges link the two main buildings, like Roman aqueducts. It was the headquarters of the New York Port of Embarkation, an operation that moved millions of troops and millions of tons of military supplies across the globe, and it remained active through the 1970s. Elvis deployed from the Brooklyn Army Terminal.

Now the structure is home to a number of corporations and industries, including electronics, textiles, and lighting. Old train tracks still run up 1st Avenue to the main entrance and then disappear into concrete, right in front of the security gate. Military buildings can be repurposed, but they can’t really be turned into something else. Several years ago, I walked through the former artillery sheds in Marfa, Texas that house Donald Judd’s 100 untitled works in mill aluminum. Before these structures became part of the Chinati Foundation, they housed German prisoners during the war, and there are still German words on the walls. These buildings have a past—a past that has something to say about the machinations of history—and this past remains, maybe as text, as at Marfa, or maybe as something that feels a little like haunting.

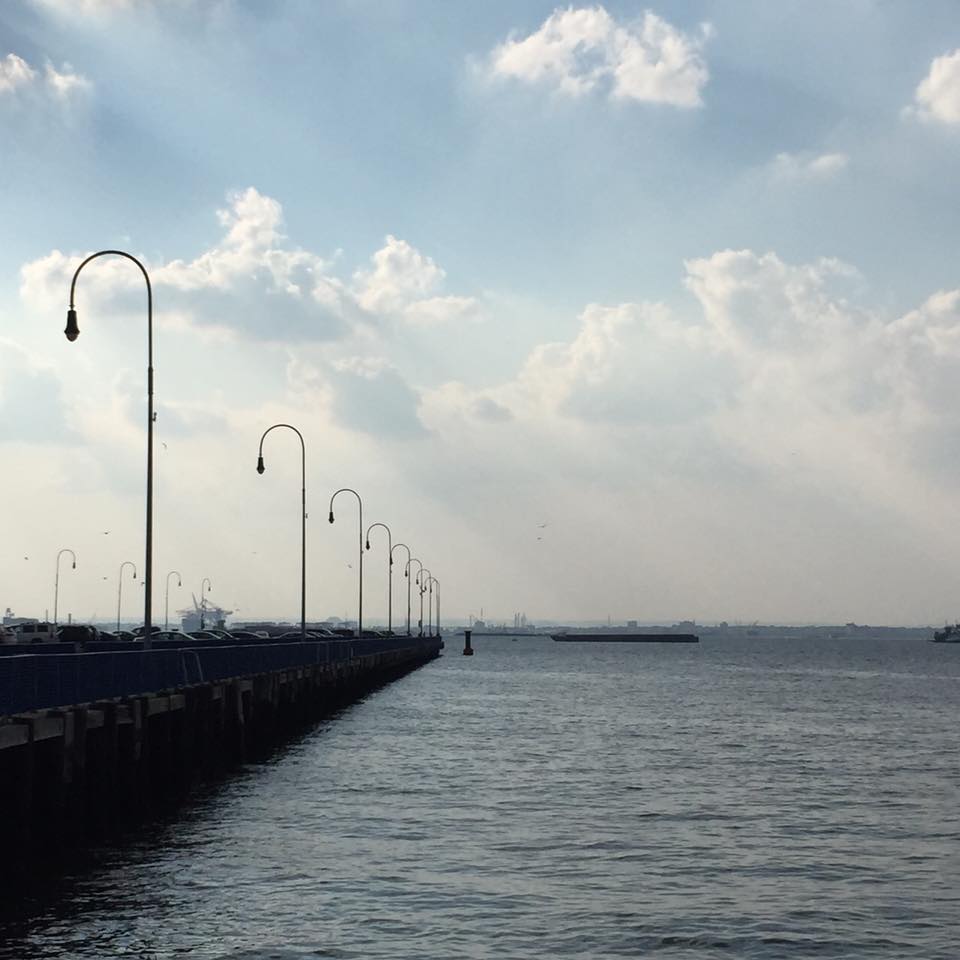

The army terminal felt haunted, if only because it was hard to imagine what went on inside it now. I sat on one of the red benches by the pier, with the building behind me, and looked across the water to the city’s skyline, hazy behind the warehouses of BWMM Meat Market.

It was always cooler out by the water, and the air smelled of metal and algae. Millie would sit and look up at me for several minutes and then, having determined that we weren’t going anywhere, she would lie down. This wasn’t a waterfront in the sense of somewhere to appreciate a view. It was an industrial waterfront: a place of work. The terminal was located on the water for practical, not picturesque reasons, as numerous discarded pallets and plastic crates testified. But the view was appealing because it wasn’t supposed to be a view. It didn’t quite count as one. It wasn’t there for me.

Doctors and nurses from the medical center passed by in their scrubs, heading to the ferry to Manhattan that leaves from the pier. Shredded plastic caught in the barbed wire fence fluttered like birds’ wings, while real gulls circled above, their bodies black in the evening light.

A terminal is a place where things end. Sitting there on the water in the evenings, it felt like an end—not just of the land, but as August wore on, of an ending in time: the end of summer. For those of us whose lives unfold on the school year, the end of summer is the ultimate ending, and it can be far more melancholy than the fall, which generally lays claim to that state of mind.

Sometimes at the end of things, if you find you need an ending, you have to impose one. The army terminal, with its incidental loveliness, was an ending for me, or maybe it was just a place where one thing became another, where land and time gave way. I thought of all the things that had come and gone from there. A place where things are received, a place where things are sent forth, a place of setting forth.

Susan Harlan is an English professor and a writer. Her work has appeared in The Guardian US, Roads & Kingdoms, The Morning News, Public Books, Curbed, The Toast, Nowhere, The Awl, Avidly, and Atlas Obscura.