The night my colleagues and I sat around the bistro table and stockpiled our grief—I couldn’t get out of bed, said one; I cried to strangers, replied another—the night we compared the protests we’d attended and petitions we’d signed and officials we’d called; the night we declared we were going broke from our impulsive, panicked donations; the night we marveled at how many specials our waiter had memorized—scores of sauces and sides; the night we failed to retain a single one; the night I showed pictures of my son scrawling “Love Wins” on pink paper; the night we traded stats like playing cards—how many women, how many stayed home—even though stats were the thing that sparked our grief in the first place; the night we realized, with fright, that we didn’t know what or whom to trust: this, my friend, is the night you learned I’d betrayed you.

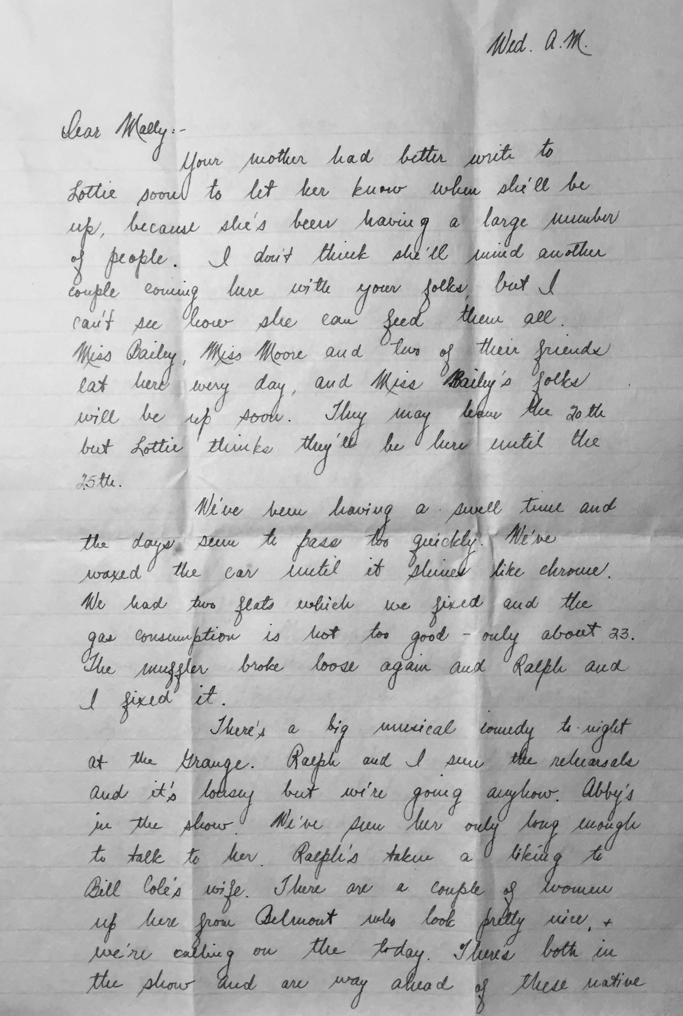

Mostly, Les gossips and writes about girls. One’s “a real peach” and another “darn nice.” Poor Esther has legs like parentheses—she “must have been born with a barrel between her legs.” Then there’s Mildred, who’s darn good-looking but too biting: “Sarcastic is no word. That’s complimenting her.” Les gets a little revenge when he sees her at a dance with “an awful dopey looking hobo.” He has a good time, even though “nearly every girl there was a pot.”

Mostly, Les gossips and writes about girls. One’s “a real peach” and another “darn nice.” Poor Esther has legs like parentheses—she “must have been born with a barrel between her legs.” Then there’s Mildred, who’s darn good-looking but too biting: “Sarcastic is no word. That’s complimenting her.” Les gets a little revenge when he sees her at a dance with “an awful dopey looking hobo.” He has a good time, even though “nearly every girl there was a pot.”