Speaking of Southern Illinois and fishing and smoking cigars and praying when you don’t believe in anything, I got a call last week from my neighbor Larry who was having a porn barbecue. “Every year is a gift,” he told me, when he turned thirty-four. That was forty years ago. He was always convinced he’d die young, or die middle-aged, or die a few weeks after he retired. He’d more or less been planning on it forever. In the past five years he’d sold his books. He’d sold his collection of toy figures. He’d burned most of his poems. “Nothing I can do about the published ones,” he’d said. “That’s my own little punishment from God.”

Essays

Driving Lessons

My old man taught me to drive on Sundays, usually when he was drunk. I was fifteen and he was a big shot on the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard, the head engineer of combat systems on nuclear submarines and surface ships. During the work week he was a sober, respectable member of the community, but on weekends he lived an entirely different life, which included bouts of sullen, angry drunkenness and unpredictable fights with my mother. He often gave me a driving lesson after one of their battles, when he was still brooding and slugging off a bottle of Wild Turkey. He’d insist we drive over to a small strip of land just off Honolulu, a place the locals called Rabbit Island, even though there wasn’t a wild rabbit anywhere in the Hawaiian Islands that I knew of.

Swimming, In Two Parts

Pools

1.

Washington, D.C., summers have been hot since forever, so a place to swim is a necessity, not a luxury. In the 1950s and 1960s, no one had air conditioning at home, and the Potomac River was so polluted that a tetanus shot was advised if you fell in. We lived in Southeast when I was little, and my parents would drive across town to Georgetown, the rich part of the city, to the public pool. My mother says I would throw myself in if she took her hand off me; she was constantly thanking people for rescuing the baby.

Summer Love: Ice Cream and Its Many Contents

In a country so hot, and with such sugar hunger, you’d think the frozen dairy dessert field in Abu Dhabi would be crowded. But the United Arab Emirates is a relatively new country, with few home-grown stores, so imported chocolates and native dates dominate the sweet shops. When it comes to ice cream, a dozen kinds of Baskin Robbins is all there is. In grocery stores, there’s Häagen–Dazs too, but it’s the jagged, sickly pink BR that dominates each and every city superblock, including one on the ground floor of our Abu Dhabi apartment building—right next to the ATM.

21st Century Oregon Trail

There are countless books written on what to do after an extra-marital affair, advice custom built for the betrayed and the betrayer. I’m not sure if any of them suggest quitting jobs, selling the house, and moving 2500 miles west to Oregon. But that’s what we did. A friend who lived there said, “There’s something to be said about traveling across the entire continent, coming to the point where there is no more land, and throwing all of your problems into the Pacific Ocean. There’s no choice but to start over.”

Neither of our families were supportive. We did all the packing ourselves and hired a truck to drive our things across country. When the unmarked semi pulled onto our narrow street, three Hispanic men jumped out ready to load everything inside. Our neighbor, an old woman whose husband—a crusty old fellow named Peck—had died a few months previous, came over and said, “I guess you all are moving then?”

Jordan Rift Valley

We came to the Dead Sea as an afterthought, five of us wedged into one taxi on our way to the airport. So far we had spent our Jordanian daylight inside a conference room, listening to other Fulbright scholars present research about the Middle East and North Africa, and our evenings in large group dinners comparing notes. Within hours, my new friends would scatter back to Morocco, Oman, and Israel, and I would return to my temporary home in the city of Al Ain in the United Arab Emirates. The conference had been delicious and heady claustrophobia, like interval training for academics. We acquired and processed new information, alternating between externalized and internalized thought, acquisition and analysis, as if variety could substitute for rest. What I’m saying is that we were a certain kind of tired. When we unhooked ourselves from the backseat of the taxi, language was beginning to hurt.

Candyland After a Neutron Bomb

“Life has gotten real complicated, and when you think of Enchanted Forest, it’s not.” –Paul Kennedy, documentary photographer of Enchanted Forest

On August 15th, 1955, a month after Disneyland Park opened its gates, the second theme park to be built in the US lowered its drawbridge for the first time to a humbler fanfare.

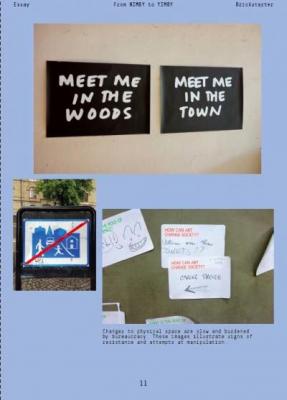

Just Say YIMBY: Design Fictions and Crowd Funding

By SCOTT GEIGER

“We talk about Brickstarter as if it already exists because we are sure it will in a few years time.”

I was excited to see +Pool return this month for a second session of crowdfunding on Kickstarter.

3 Movies: In Conversation

These were not snapshots, but motion pictures – hence, “movies.” Or rather, they were “talkies” – sound happened too. And through editing there were unions and disunions of movement and sound, the building of story, of character. In the span of seven weeks I watched three.

Things we experience in close proximity in time come to bear on each other, bridge the gaps between them. Persons in close proximity attempt a similar bridging.

The first movie was a drama, imagined from the ground up. The other two were documentaries crafted from ongoing lives. Each brought a unique document of a couple-at-home to the screen in my home.

Vanishing Chinatown

I know the Chinatown, New York, of long ago from my parents. My grandfather, like a grand impresario, hosted their wedding reception there. They were married on September 19, 1959, and he personally invited everyone to the reception, stopping by at the Gee, Lai, and Gong family association buildings, which was where men gathered to consolidate finances and dictate business decisions, and where women met to socialize. Once invited to the reception, you could bring any number of family, but it was a matter of honor not to overstep the generosity of the invitation. I should add that the reception lasted for three consecutive nights.