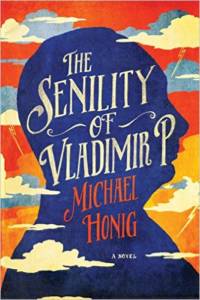

By MICHAEL HONIG

Reviewed by OLGA ZILBERBOURG

Nikolai Sheremetev, the protagonist of British novelist’s Michael Honig’s second book, is a Moscow nurse. For six years, he’s been looking after a private patient suffering from dementia. The patient’s condition is deteriorating. Prior to his illness, Vladimir P. had been a president of Russia. After his confusion grew and he could no longer hold his own in public, he was quietly replaced by a member of his team and sent into retirement to a private estate near Moscow. As Vladimir’s mental acuity deteriorated, Sheremetev became the single point of contact between him and the outside world. Sheremetev manages his daily schedule, his medications, his rare outings.

“One late afternoon in June of 1880, a rather famous woman sat in a railroad carriage traveling toward Venice with her new husband, a handsome young man twenty years her junior.” Thus begins this accomplished tale, in which the honeymoon of a sixty-year-old bride is the frame for the life story of a woman who defied convention but had no wish to.

“One late afternoon in June of 1880, a rather famous woman sat in a railroad carriage traveling toward Venice with her new husband, a handsome young man twenty years her junior.” Thus begins this accomplished tale, in which the honeymoon of a sixty-year-old bride is the frame for the life story of a woman who defied convention but had no wish to.