“My way is so long, so long, but my road is foggy, foggy,” reggae legend Winston Rodney, aka Burning Spear, chants on his 1980 song “Road Foggy.” The beat sways underneath him like a horse plodding on a mountain track, and the horns sound muted and distant through the mist. It’s a song about the song as journey, a track that feels like it’s never meant to end. You travel not to get to get to the end of sound, but to luxuriate in it. As Spear said in an interview, “If I walk away from music, I walk away from myself.”

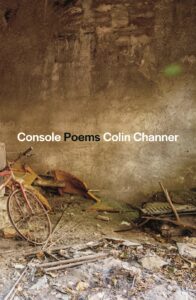

Colin Channer includes that quote and the line from “Road Foggy” in several poems in his recently released second collection Console (FSG). The volume is suffused in dub and reggae recordings he loves from his homeland. Dub is not just something left behind, though. It’s also a metaphor for the way that Channer’s own experience and existence makes Jamaica live in his new home of New England, and vice versa. Music creates an imagined space in which disconnection is its own coherent landscape. The consolation is that the places you go are both where you’ve been and who you are.

Channer’s poetry in Console builds on the innate contradiction of popular recorded music, which is rooted in a specific location and community, but can, via the magic of technology, travel anywhere. Or as Agnés Gayraud explains in The Dialectic of Pop, roots music “sings intransigently of its place of origin, the local and communal forms of life from which it was born, but which are now behind it, lost forever.” These contradictions are heightened in Jamaican dub, a music which relies on the recording studio—the “console”—to manipulate, stretch, reverberate and estrange Jamaica’s communal sound. As Channer says in “Picturebook Brockton,” “Roots, dub is a republic. Here we mass/and nourish on bass made glutinous, hallucinate by will.”

For Channer, that hallucination is the vision of a community that has the contours of diaspora carved into its native soil, or (more precisely) into its native sound. Jamaica can’t be contained, and was never meant to be contained in Jamaica. And so the farther from home he goes, the more he finds himself in, and as, a homeland. “The Elizabethans rode riddim, bedazzled,” he declares, banging a “scansion drum” that rolls Donne and Walcott and Toots into one languid, taffy-elastic, deep-bottomed beat. The last poem in the collection, “In Fuguing Wake,” dedicated to New York poet Amy Clampitt, is set in Tanglewood, where “mosquitoes will chorus/picknickers will gnat and I will camp.” The humid summer of Massachusetts is a palimpsest over the humid summer of the Caribbean as Channer listens to Liszt with “a shake at breastbone” that echoes dub’s deep throb.

Channer’s most explicit exploration of everywhere as Jamaican landscape may be in “Lent,” a poem which begins:

I mount a crest in coffee country and it’s Oregon.

In all directions, ridges saw the Caribbean out of view.

In these wet mountains, clichés of the tourist

board elapse, beach fables die famished…

Channer is walking through the highlands of Jamaica, and the view, to his eyes and imagination, is more stereotypically reminiscent of Oregon than of the Caribbean. The vision of Jamaica and Oregon switching places reminds Channer forcibly that he’s really home in neither. “I left this island early; never learned to love with value/my language,” he says, but at the same time, “I’ve never lived on/the West coast much less Oregon.” A New England transplant, he’s walking neither here nor there, strolling through a place that doesn’t look like his and isn’t his.

The lines in “Lent” are long, reflective, meandering. Channer is deliberately evoking a history of romantic landscape poetry parodied and distilled in John Ashbery’s “The Instruction Manual.” In that poem Ashbery’s narrator imagines Guadalajara— “City I wanted most to see, and most did not see, in Mexico!” The subaltern here doesn’t speak, and doesn’t exist; he is an entirely imagined other, a tourist’s dream to distract from the ho-hum boredom of bureaucratic office-work at the imperial center.

Channer acknowledges some kinship with the bureaucrats; he acknowledges that he may “share the dubious heritage of gaze, of making all before me/what I want, gating my imagined, seeing me in everything…” The poem also says, though, that he is “colonizing in reverse.” Where Ashbery starts in a nonspecific implicitly American office space and turns it into an imagined, vivid Guadalajara, Channer walks in a very particular part of Jamaica (“the forest, green is dense as smoke”) which transforms into (an imagined) Oregon. If colonizing is when those in power claim a land as theirs to imagine and control, colonizing in reverse might mean reasserting one’s own belonging in the face of imperial dreams that tend to erase the reality of colonized people in all spaces, here and there.

In “Lent,” the transformation of landscape isn’t creating an imagined imperial dream, as per Said’s Orientalism. Rather, the Oregon Channer sees in Jamaica is an extension of the landscape’s potential. Channer isn’t escaping or conquering; he’s turning up the soil to find another, buried aspect of Jamaica, one of his homes. “The remix is dub’s premise. Reggae conquers. Not maybe actual./But how it sees the world. There is more to say on this.” Channer highlights that he could say more because the nature of dub is that there is always more to say. A familiar track can be picked up by someone else who lives close by—Lee Perry, King Tubby, Scientist, Sly and Robbie—and twisted up, slowed down, spread out, till you can hear the Pacific Northwest rumbling in the Caribbean.

As with dub, so with poetry. Dub’s producers evoke touching grass in sweltering studios with no grass in sight (or not that kind of grass, in any case). Similarly, Channer isn’t actually walking through Jamaica any more than he’s walking through Oregon. Poetry is words for a place, not the place itself; as in records, the roots are uprooted.

“In some language somewhere there has to be/A word that means melancholicallybewildered,” Channer muses in “Unconsoled.” But there is no such place and no such language; meaning is always floating free of its source. He calls his neologism “[a]n anfractuous set of glottals, slipping vowels/Like a counterwailing helix of wet stone stairs.” The clotted mutli-syllabics roll around your tongue and throat, thick enough to taste, even as the imagery scuttles off into the abstract helix of metaphor, leaving Channer behind, melancholicallybewildered. In searching for a new place and a new meaning, though, you create that meaning. The word that means “melancholicallybewildered” is now “melancholicallybewildered,” and the language that it’s in is this one.

Channer quotes Marshall McLuhan—“We become what we behold”—in “Hurricane Suite,” a poem interspersed with photographs of flooding from the archives of The Providence Atheneum. The idea that we’re doomed to turn into the image or the place we craft for ourselves can be an ominous message if you see images as artificial projection. In creating a new language, a new image, or a new context, are we turning ourselves into empty, uncanny valley images?

But with a little tweaking and the turn of a few dials, “We become what we behold” can also be a consolation. Authenticity and community aren’t some sort of abandoned freight forever left behind. Your self is what you see (or hear) where you are right now—be it Tanglewood and Lizst or Oregon in Jamaica on Spear’s foggy road.

The first poem in Console is “Spumante.” Channer/the narrator is walking again, this time in a New England winter along the coast. He sees a dead, probably human-killed, whale, and identifies with it strongly:

There is slave in me, fat heritage

no fluke I’m invested with hurt,

echo of the hunted, located, natural

rights redacted, meagered to resource.

The whale, then, becomes a symbol of enslavement and exploitation; it has been displaced, as Channer’s ancestors were. To honor the dead, and to resettle himself, Channer turns to music when he gets back to his office, picking up his “Fender, ancient black thing”:

I hum, thumbing, fashion something of a home,

Some succor, pulse quick but steady as I deep dive

To dub. With it comes the baleen

Wheeze of mouth organs, plangent blue whoop.

I am dub and dub is water.

Water is where the whale lives, so becoming dub in the poem is becoming one with nature and with one’s natural place; it’s a lowering into where one belongs. But water also flows and changes shape; it’s a place that isn’t a place or that can be every place, a home living in some evanescent hum.

If you can put roots into water you can put roots into anywhere. It’s a matter of imagining yourself into the whale or the console or the New England shore. The dream of diaspora is that you can dream yourself into any place, and any place into you. “Seeing relations of what ought to be disparate/is my living, my burden, my habit, my gift,” Channer writes. And he quotes Peter Tosh, singing back as a kind of echo: “I am that I am I am I am I am.”

Noah Berlatsky (he/him) has a number of chapbooks forthcoming, including Send $19.99 for Supplements and Freedom (above/ground), No Devotions (LJMcD Communications) and It’s Fab (Origami Poems).