By ANNELL LÓPEZ

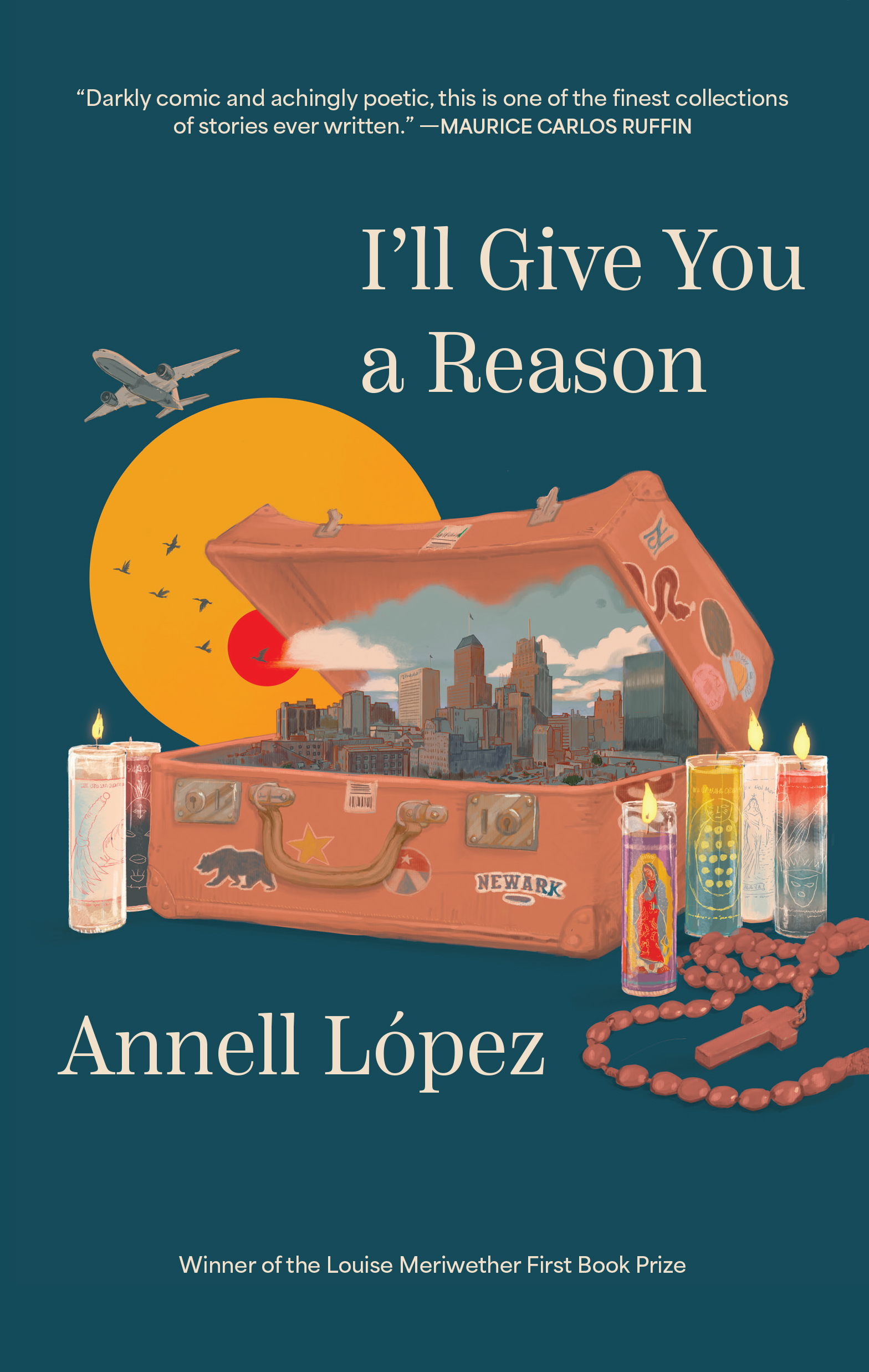

“Dark Vader” is excerpted from Annell López’s I’ll Give You a Reason, out now from Feminist Press.

I was registering for the GED when Junie stormed into the house, slamming the door behind her. Her heavy Princess and the Frog backpack fell off her shoulder; the drop made the hardwood floors of our walk-up tremble.

“That was a bit dramatic,” I said. But she didn’t laugh. I closed my computer even though I wanted to finish registering for the test. The way Junie came in made me feel like I needed to give her my attention.

She threw her bubble coat onto the couch, then removed her snow boots, socks and all.

“They keep calling me Dark Vader,” she said.

“What?”

“Dark Vader! Every time they see me, they giggle and say Dark Vader.”

She took a deep breath, then slowly released a lungful of air, the way our mother taught her. The way I couldn’t figure out how to when I was her age. She looked at me. “Who is Dark Vader?”

“You mean Darth Vader?”

“No. Dark with a k.”

I pinched my nose like I was trying to stifle a sneeze. But truthfully I was trying to stop myself from laughing at the fucked-up ways kids were inventive. Junie was eight, too young to know who Darth Vader was, or to own a smartphone to look him up on—not that it stopped her from begging for one. I opened a browser on the laptop. Junie stood behind me, puffs of her banana Laffy Taffy breath brushing my cheek.

“That’s Darth Vader,” I said.

I turned and watched her eyes shift from side to side. She was the spitting image of our mother, only much darker. I readied myself to hold her on my lap and explain the whole Darth Vader bullshit with as much empathy as possible. It wasn’t the first time kids had baptized her with some catchy nickname. Last year, when she joined the dojo on Niagara Street, an older kid referred to her as Blackie Chan. Our mother refused to explain to her what it meant and instead allowed Junie to believe Blackie Chan was not only real, but so strong he could karate-chop cinder blocks in half. Our mother embellished the idea of this fictional Blackie Chan so much that Junie thought his strength came from his Blackness. She assumed, naturally, that the color of his skin needed to resemble that of his karate belt.

On the computer screen Darth Vader stood defiantly, holding a lightsaber in front of a crew of stormtroopers. Junie folded her arms at the indignity of it all. “I get it,” she said. She shifted her gaze to the coffee table where my phone had started buzzing. “Your phone, Vanessa.”

“I hear it.”

“Who is ‘M’?” she asked. “Is that Mami?”

“No.”

It was Mateo. But he was my boss, fifteen years older, and still married. I couldn’t bring myself to save his number under his actual name. I flipped the phone over. Junie looked at me.

“I’m sorry they’re calling you names,” I said. “Kids are stupid.”

She shook her head. “Whatever. I don’t care.”

It was as if saying those words out loud made them true. Within seconds her expression softened. Then she smiled and lunged her arms at me. I embraced her. I was twenty-four and Junie was eight. Our sixteen-year age difference had warped our reality; I always felt like she was my daughter and not my little sister. It’s what everyone thought, anyway. I had dropped out of high school one winter, and Junie was born the following spring. I hadn’t even had a boyfriend at the time, but the variables were there, asking to be shaped into a narrative that made sense: Baby equals dropout. Dropout equals baby. If it walks like a duck, then it must be.

I’ve woken up from dreams where she is mine: dreams where I come out as a mother and all of a sudden I have an external reason for bettering myself—a human being whose needs wipe away my feelings of inadequacy, and the crippling anxiety that keeps me from passing the fucking GED.

She squeezed me tighter. “I love you,” she said.

Our mother had named her after the month of June, which wasn’t the month when Junie was born but the month our mother had trekked the Mona Passage from Santo Domingo to Puerto Rico by boat, eventually making her way to New Jersey. It took her the entire month of June to make it to Newark. So she named her second daughter Junie, to remind herself that America was for second chances.

“Junie,” I whispered. “Want me to fuck somebody up?”

She giggled, then shushed me. “You’re gonna get in trouble with Mami,” she said.

Our mother hated my cursing, especially in front of Junie. But whether I cursed or not, my mother was usually angry at me. She had her reasons. Her anger, her disappointment, they went far beyond my lack of a high school diploma. I had betrayed her. I had spat on her American dream.

“Violence is never the answer,” Junie added.

The same message had been relayed to me all through- out middle school. Not that it registered at the time. For as long as I could remember, everything would spark a flame in me, and I’d fan those flames until they engulfed me. By eighth grade I’d been in over a dozen fights, two of which landed me in long-term suspensions. I had a few souvenirs: a small scar at the corner of my right eye (from hitting the edge of the curb), a crooked ring finger (from punching a wall), and a shitty relationship with my mother (from all of the above).

Shortly before Junie was born, things got worse for me at school. In the winter of my junior year, I’d been sitting quietly in Ms. Gomez’s biology lab when a beaker fell. I hadn’t dropped it—at least I don’t remember doing it. Not that it mattered then, because Ms. Gomez had stiffened up like one of her taxidermied birds and headed toward me, ready to humiliate me for something I hadn’t done. Before I knew it, I’d struck her in the nose. Mami was too humiliated to attend any of the meetings that followed, so I never went back to school.

Junie wasn’t like me. Junie didn’t hold on to anger. Insults would slide off her like water down a glass window.

“When is Mami coming home?” she asked.

“I’m not sure.”

Mami had picked up extra shifts. After our last fight— when she said my bartending job was ungodly—she refused to let me help out with bills. I had told her I’d gotten a new job at a law office above Penn Station; I no longer worked at that seedy tavern she hated so much. She’d said, “Doing what? You don’t even have a high school diploma.” No matter how hard I tried to talk to her about my new job, she wouldn’t hear it.

We hadn’t had a real conversation in weeks. We lived like roommates who could not stand each other and only spoke when it was absolutely necessary. Despite how much I had disappointed her, I made her life easier. Why couldn’t she see that?

I wasn’t lying to her. Mateo had gotten me a job as an office clerk after a speech about how he, too, was once poor, how his parents had come to the United States from Portugal with nothing but fifty-six dollars in their pockets. I’d asked him to calculate inflation and give me the real sum. He’d kissed my stomach and said that didn’t fit the narrative.

At twenty dollars an hour, the job was the best thing someone like me could find. It was better than wearing an Elmo costume to pose with tourists in the middle of Times Square or, most recently, wearing a plunging neckline to pour Yuengling at the tavern where I’d met Mateo.

Behind us in our kitchen, the old furnace clanged and banged, warming the air. Junie picked up her coat and hat off the couch without my prompting. She took a stack of books from her backpack and set them on the table, then began to do her homework.

Though it was only five o’clock, the sun had already gone down. I resisted the urge to text Mami because if it wasn’t about Junie, more often than not she would ignore me. There were leftovers in the fridge from a few days ago, a tray of Portuguese barbecue: some pieces of rotisserie chicken, yellow rice, and an overdressed salad of wilted iceberg lettuce and tomatoes.

Junie looked at me. “Mac and cheese?” she said. She was perfectly content eating the same lousy dish several days in a row. But I was taking holiday photos at my new job in two short days, so I refused to eat anything that would make my cheeks look puffier than they already were. “We need to expand your horizons, young lady.”

“So pizza?”

I shook my head, but she insisted.

“Fine. I’ll grab a smoothie for me and a slice for you.”

She nodded in agreement, then went back to her homework.

“I’ll be back in fifteen minutes. Don’t move from that table.”

I stopped at the foot of the stairs to check my phone, which kept vibrating in my pocket. One missed call, one voicemail, and a text message. All from Mateo. I opened his message: a picture of a bulge poking through the open zipper of his navy slacks.

Is that yours? I replied. I waited for him to respond. Forty wasn’t that old, but for some reason it always took him forever to text back.

Your turn. Spread them for me, he texted.

I can’t. I’m with Junie.

Can I see you tonight?

I don’t know, I wrote. It’s not Thursday yet.

It was his rule. A way, he’d told me, to exercise control at a time in his life when everything existed outside the lines. I wanted to believe he was telling the truth, that he was not still with his wife. Either way I thought it was endearing, the idea that we could control anything.

Downstairs, Ms. Maxwell, our neighbor from across the street, shoveled snow onto the parking spot in front of our apartment. I stopped next to it, keys in hand, and looked at her.

“I just need to move my car for a moment,” she yelled. Her old Buick had been left in the same spot for weeks, but because she was a crossing guard and a friend of folks in high places in the city, her car had been left unbothered, even on street-cleaning days where cars left on the wrong side of the street were quickly towed away. I crossed the street. Wind whistled around me. Flurries of snow and bits of ice struck my cheeks like tiny daggers.

“I shoveled that spot for my mom,” I said. She looked at me and nodded the way people do when they don’t understand what’s going on. She didn’t hear a word I said.

“Excuse me, Ms. Maxwell, I shoveled that spot for my mom.”

“Yeah, but you guys don’t own that spot,” she said. “You guys are renters, not homeowners, dear.” She said it with a smile. In fact, she always spoke with a smile regardless of what came out of her mouth. Her dog ran out from inside the shed and stood at the gate, barking.

We were indeed just renting this apartment. People up and down this street had a way of making distinctions between who owned and who rented. She was right that the spot didn’t belong to us, but it also belonged to no one. Besides, I had gone to the trouble of shoveling it.

“Can’t you just pile the snow somewhere else?” I asked. Her dog was still barking, but she didn’t even look his way.

“Where am I supposed to put it, sweetheart?” She smiled bigger this time, baring her optic-white dentures. All around us, piles of rock-hard snow stood tall, waist high. It had snowed weeks ago, and the sun hadn’t shined hot enough to melt it since then. Ms. Maxwell was right that there wasn’t anywhere else to put the new snow. Years ago I would have told her to shove it. But I wasn’t that girl anymore.

“Do you really need to move your car? It’s so dark and slippery,” I said, smiling.

“All right, all right.” She grabbed her shovel and headed back inside. Her dog followed.

I looked to the end of the street. People were returning home from work. They were salting and scraping and shoveling away, trying to make room for their cars. Suddenly the walk to the pizzeria and the café no longer felt like a good idea. I turned back to our place, then ran up the stairs.

Junie waited for me at the door. “I saw you talking to Ms. Maxwell. I watched you from the window.”

“She was dumping snow on Mami’s spot,” I said.

“I don’t like Ms. Maxwell,” she said, and I couldn’t help but think how much I didn’t like Ms. Maxwell, either. The lady had been a crossing guard since the first coming of Jesus. She was a permanent fixture in the neighborhood. People came and went, things changed, but Ms. Maxwell was always there, reporting to the school the events she’d witnessed around the neighborhood: who had fought, who had stolen candy from the convenience store. She even knew who’d tried to sneak into the go-go bar blocks away from the school.

I took a deep breath. “Why don’t you like her?”

Junie waited for a moment. It seemed as if she was trying to decide whether telling me was a good idea.

“I’m not gonna do anything to her,” I said. “Trust me. If I really wanted to, I would have done so years ago.”

“Okay,” she started slowly. “I think she laughed when they called me Dark Vader.”

“You think or you know?” I asked.

“Yeah, she laughed.”

“Who’s calling you Dark Vader, anyway? You haven’t told me.”

She paused and wrinkled her mouth, considering the question. “Dylan and Joseph.”

“Ms. Maxwell’s kids?”

“Grandkids,” she corrected.

“Color me shocked.”

“What?” she said.

“I’m not surprised.”

She looked at me. Her eyes glistened and for a moment I wondered if there were tears waiting for permission to be released. She was, after all, just a baby; even if she was strong, even if she’d learn to cope with mean words, they had to be stored somewhere.

I looked at the clock. It was 6 p.m. Mami would be home soon, tired from twelve hours of smiling and standing in the cold outside the high-rise, opening doors for rich people in Jersey City.

I walked over to the pantry and grabbed a single-serving cup of mac and cheese and a handful of broccoli florets from the fridge and nuked both in the microwave.

“Eat all of it,” I said to Junie.

I grabbed a hat and a pair of gloves, resolved to camp out in the cold to keep that parking spot open, however long it took. I laid a towel down on the stoop and felt the cold travel from the concrete through the fabric of my clothes to my skin.

I turned and saw my mother down the street, walking toward the apartment, holding her ridiculous bell cap with one hand. She looked silly, but she liked the job most days. The tips and Christmas bonuses made it worth her while.

“Why are you out here?” she said.

“I was saving the parking spot for you. Where’s your car?”

She pushed the door open with her shoulder. “I took the train home.”

“Well, yeah, obviously. But where’s the car?”

She shook her head, then started up the stairs. It’d been a while since she could climb all three floors without stopping to catch her breath. Today she seemed hell-bent on making sure I saw how she could swiftly walk up without so much as a pause between floors.

“I left the car at the parking garage at work,” she said. “It’s too hard to find parking here.”

“There was no need for that.”

“How would I know that you were saving the spot for me?”

“Because you should know better. And also, you could just text me and ask.”

“No, gracias.”

I walked past her and straight into my room. There was so much I wanted to say to her, about Junie, about Mateo, about me. Instead I sat on the bed. I couldn’t force her to speak to me regardless of how much I wanted her to know that, sure, my relationship with Mateo was problematic, but I was trying my best to get somewhere, to be something that’d make her journey to this country worth a damn.

I should have insisted that we talk, but it was easier to move on. So I responded to Mateo’s text instead. What do you have in mind? I wrote, though I already knew the answer.

*

The hotel room smelled like citrus and lavender. It wasn’t pungent, but it was a bit much, and it made me wonder if the scent was meant to mask something else. Nondescript landscapes adorned the peach stucco walls: generic images printed on cheap canvas. The place was clean, but it wasn’t necessarily nice.

Mateo kissed the back of my ear and traced his fingers along the nape of my neck, down to the small of my back. In a whisper, he asked if I was hungry and offered to order in. I told him I wasn’t hungry. I didn’t want food. Not when so much else was taking up space. What I wanted was to talk, but his zeal, his desperation, fizzed over like Coke spilling from a bottle that’d been shaken and shaken.

He kissed me again, then pulled me closer, his arms wrapping around me. I felt his penis harden against my lower back. He grabbed my hip firmly and flipped me over. Sliding his hand down my thigh, he grabbed me by the knee and pried my legs open. “Maybe you’ll be hungry after this,” he said.

He pushed his face between my thighs, drawing circles with his tongue. For a second, the world paused: the impending deadline for the GED, the holiday photos, my mother, Junie, Dark Vader; it all began to disappear. I felt myself dissolving like a sugar cube.

But then he stopped.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“You’re not making any noise.” He wiped his mouth and nose on the sheets, then sat up at the foot of the bed.

“Why did you stop?” I asked.

“Because you didn’t seem to be enjoying it.”

“I was enjoying it. I just have a lot on my mind.”

He took a deep breath. “Do you want to talk about it?” he asked, sounding deflated.

I didn’t think I could. I didn’t have the courage to tell him I no longer wanted to live in this nebulous space. I wasn’t naive enough to delude myself into thinking I would ever be a wife or a girlfriend. Girls like me don’t build castles out of sand. Regardless, I was getting tired of being the girl he’d drive to a hotel off the turnpike once a week.

“I’m okay,” I said.

He began to kiss my calves. “Where were we?” he said, holding on to my ankles.

I stared at the one painting in the room that wasn’t a landscape: a painting of the ocean, foamy waves crashing on the shore. It reminded me of my mother. To have crossed the Caribbean Sea on a boat, the sun, sea, and salt scorching her skin, only to get to the US and have a twenty-four-year-old directionless dropout for a daughter. What the fuck was I doing?

I grabbed a handful of Mateo’s black hair and yanked it toward me. I moaned, even though I felt nothing.

*

Mateo left the room at the crack of dawn and didn’t return. I woke up to several messages on my phone. He’d texted me heart emojis, along with an apology for disappearing. In a separate message he urged me to take the day off, to “get some much-needed rest.” The room was already paid for and checkout was at eleven. But even if I’d tried, I couldn’t have spent any more time in that room. The more I breathed the artificially scented air, the more I felt cheap, like the ceramic lamp resting on the plywood night table or the patterned rug or the artwork hanging on the walls. It all made me want to shed my skin.

The other messages were from my mom, reprimanding me for not texting her to let her know I’d be spending the night elsewhere. It surprised me. I’d been spending nights with Mateo for a while, and she had never seemed to care. She hadn’t texted to check on me in months. For a long time it’d felt as if her only daughter was Junie, and I was just an appendage she was forced to carry. Her second message was a reminder that there was a GED bootcamp at the library. I’ll look into it, I wrote.

I had failed the GED numerous times, but it was never because of the material. I could read a passage, then answer comprehension questions using supporting evidence. I could calculate how much a hypothetical housewife would have to pay for six hours of a carpet steamer that rents for $12.85 per hour. I could read and interpret a graph and a pie chart. What I couldn’t do was stop the sweat from pooling in my palms. Or the stomach pains. Or the nausea. Or the panic attacks. I couldn’t stop picturing my former high school classmates flipping their tassels from left to right and tossing their graduation caps in the air.

I checked out of the hotel, then went to the library like I’d told my mom I would. I sat in the front of the room. It wasn’t my first time attending some remedial course to help me prepare for the test, but it was the first time in a long while that I felt a surge of hope. Just being there meant something. At the very least I could go back home and tell my mother I had gone, even if nothing came of it. Even if, in the end, I’d end up failing once more. At the very least I could tell her I tried.

The instructor, a young woman with at least a dozen beaded bracelets dangling from her wrist, began the class with a meditation exercise. She told us to close our eyes and imagine ourselves in the future. I looked around, perhaps expecting some defiance, but everyone kept their eyes closed, surrendering to the exercise. If it was good enough for them, it was good enough for me, so I closed my eyes even if I couldn’t picture the future. After a minute or so, she suggested we introduce ourselves. She said if we knew more about one another, the reasons why we were there, we might be more likely to hold each other accountable. Though I wasn’t looking forward to sharing anything about myself, I knew she was right.

At her urging, a couple folks stood up one after the other. A woman, probably in her thirties, said she was embarrassed. She’d spent years working, raising children, dealing with life. She was glad she was here now. A young man with locks followed. He introduced himself and shared that he’d played too many video games in high school. It was an addiction. He once spent an entire year at home, unable to leave. He would rarely eat or shower. It took several years of therapy to unglue his hands from a game controller. This test, this class, was his new beginning.

It took everything in me, but I stood up and waved. My legs trembled, and it felt as if my knees would buckle. I could feel my heart hammering against my throat. “I’m Vanessa,” I said. “I was suspended a few times in school because I’d get into a lot of fights. I was so embarrassed that one day I never returned. I’ve attempted to take the GED a few times. I’ve failed again and again. But I hear your eighth time is the charm.”

Around me people laughed and cheered. The instructor walked toward me, placed her hand on my shoulder. “I’m so glad you’re here,” she said.

She handed out registration forms. Feeling empowered, I took one. I filled it out even though the test was in the middle of the day, the same day as the holiday photos at work.

*

In the afternoon Junie came home sulking. The kids hadn’t stopped calling her Dark Vader, even though she’d told her teachers. She said it’d gotten worse because even the dark-skinned kids had joined in, and during recess someone had pointed at her hair and said her curls, shrunken and bunched up from her winter hat, looked like Darth Vader’s helmet.

Can I see him again?” Junie asked.

“Darth Vader?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Just because,” she said. She stood on the tips of her toes and craned her neck upward. “Pretty please.”

I googled Darth Vader on my phone and showed it to her. She held the phone close to her face, zooming in on the image.

“I do not look like him,” she said, her voice cracking. “What does he do?”

I thought about it for a second. “He’s a villain.”

“Can I watch a video?”

“Nope,” I said. “That’s enough Darth Vader for the day.”

I got a pack of dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets out of the freezer and shook some of them into a pan. I texted Mateo, They haven’t stopped calling her Dark Vader.

Tell your mom. You’re not Junie’s parent.

It’s not that I thought I was Junie’s parent; Mateo knew that. He knew what Junie meant to me.

Are you busy? I asked.

I don’t really have time to talk right now, he wrote. I tried to convince myself that maybe he was in the middle of something. Regardless, his response stung. I’d made time for him yesterday, even though it wasn’t Thursday.

Well, that sucks. I really needed someone to talk to.

I put my phone on Do Not Disturb, then slid it back in my pocket. I wasn’t asking for much. I didn’t even get to tell him I registered for the GED and would need to leave work early to take the test.

I looked over at the pan. The brontosaurus looked golden. The T. rex on the right needed more time. Chicken nuggets alone weren’t enough for dinner, so I grabbed more broccoli. It needed to be eaten.

Junie stared at me from the kitchen table. “Can you cook the broccoli?”

I moved the T. rex over, then placed a handful of broccoli in the pan. The meal looked pitiful. She deserved broccoli that, at the very least, was properly seasoned. She deserved real chicken! Not leftover cartilage and fat, compressed and molded into the shape of an extinct animal. She deserved better. I did too.

*

The day of the photo, I arrived at work forty minutes early. I’d been getting there early since Mateo gave me the job, but now that the office had hired a handful of peppy interns with eager dispositions and the willingness to work for free, arriving fifteen minutes early was no longer enough.

Around nine o’clock, people began to trickle in, filling the space with light chatter. I sat in my cubicle—headphones on—listening to an audio file I had just transcribed. Laurie had assigned it to me because the file was in “that Caribbean Spanish.” She had wrinkled her mouth when she said this. It made me blink twice.

As I sat there double-checking my work, I saw Laurie approach, Venti cup in her right hand.

“I’m done with that transcription,” I said.

“Okay-great-thanks!” said Laurie, almost breathless, each word colliding into the next. “I want to talk to you about something, actually,” she added.

I straightened my back and removed my headphones.

“So we’re taking the pictures at noon,” Laurie began. She placed the cup on my desk, then leaned in. “So for the picture we just want to make sure we look super-duper professional from top to bottom, you know? Not just our clothes but also our makeup and hair, you know?” This she punctuated with a nod, as if prompting me to nod. So I nodded, having understood her subtext.

“We’re gonna have to lean really close to make sure we all fit in the frame. Just need to make sure nothing blocks anyone’s face. We’re going to send these pictures out as holiday cards. Isn’t that neat?”

I nodded again, forcing a smile. Laurie grabbed her coffee and pivoted to Yesenia’s desk. The only other girl whose curls resembled mine. I watched from my desk, registering the tilt of Laurie’s head, the way her head moved up and down like a bobblehead on a car dashboard. Every movement was rehearsed. There was nothing authentic about her pretend concern, no output of genuine emotion. I walked over to Mateo’s office and knocked on his door. He looked up from his desk, frowning.

“I think Laurie just asked me to switch up my hair,” I said.

“Close the door,” he said. “Listen, I’m sure that’s not what she meant.”

I sneered. “You don’t even know what she said.”

He sighed and rolled his eyes.

“Unless you do know what she said to me.” He went back to whatever he was doing without saying another word.

*

I walked to the nearest pharmacy and picked up a pack of hair ties, a small tub of gel, and a brush. I was the Dark Vader at work. No matter how fast or accurately I typed, or how well I code-switched, I was made to feel indebted to Mateo for the life raft he’d thrown my way.

I approached the register and placed my things onto the counter. The cashier picked up the tub of gel and turned it over to read the ingredients.

“Is it good?” she asked.

“I’m not sure.” It was a “strong hold” no-name-brand hair gel for less than three dollars. It couldn’t be great. “I just need it to fix my hair real quick,” I added.

“Oh, but your hair looks great,” she said. And it did. I’d deep conditioned it this morning. I’d used a diffuser to make sure my curls were defined.

“Can I use your bathroom?” I asked.

“Sure. All the way down aisle nine, to the left.”

In the bathroom I thought of texting my mother. What would she do? But there was no point in doing so. I wasn’t good enough for her. I wasn’t good enough at work.

I wetted my hair and parted it in the middle. I squeezed gel onto my palm, then smeared the sticky product on my hair. Within seconds, I felt naked. My hair was supposed to frame my face. I dabbed a bit of lipstick on, then straightened the collar of my button-up shirt. I thanked the cashier on the way out.

Back at the office, a couple of interns were setting up the backdrop for the staff holiday photograph, hanging garlands and Christmas lights and placing gift-wrapped pots overflowing with poinsettias. Mateo stood across the room, smiling that vacant, mechanical smile. Like most days, he didn’t look in my direction.

I touched my now slicked hair and thought of Junie. This morning she’d asked for pigtails. She also wanted to forgo wearing her winter hat. How long until she ran out of deep breaths? How long until she started balling up her fists? The more I thought about her, the less I cared about the holiday photo, or about Mateo, or about my mother, or the GED. Junie was, and had always been, the one thing I felt good about. The one thing that made my world feel right. I stopped by my desk and grabbed my purse. I walked toward the elevator and leaned against a cement column, watching as Laurie and the photographer rearranged everyone. People pivoted and turned their bodies sideways. Some were moved to the front, others to the back. Yesenia, now wearing her hair in a bun, and anyone with a tan were strategically peppered throughout the group. Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas Is You” blared from a set of speakers. Mateo stepped out from his position and swiveled his head from left to right. I pressed the down button for the elevator and waited. Right as I heard the ding of the elevator, Mateo locked eyes with me. He patted the front pocket of his suit jacket, followed by the pockets of his slacks, as if searching for his phone. I didn’t think he would actually text me. And he never did.

Downstairs, I removed my lanyard and threw it in the trash can next to the exit. I pushed through the revolving doors. Frigid air struck me, so I folded my arms and walked faster, heading toward Junie’s school. It was lunchtime, and Junie’s teachers would be standing in the courtyard, watching the children play, trying to make sure they kept their coats on. I knew they weren’t ready for me. But I was ready for them.

Annell López is a Dominican immigrant. She is the author of the short story collection I’ll Give You a Reason, winner of the Louise Meriwether First Book Prize. A 2022 Peter Taylor fellow, her work has received support from Tin House and the Kenyon Review Workshops and has appeared in American Short Fiction, Michigan Quarterly Review, Brooklyn Rail, and elsewhere. López is an Assistant Fiction Editor for New Orleans Review and holds an MFA from the University of New Orleans. She is working on a novel.