By CHARLES YU

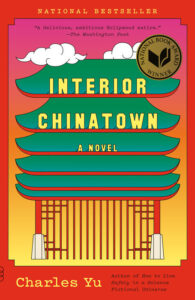

Amherst College’s sixth annual literary festival will take place virtually this year, from Thursday, February 25 to Sunday, February 28. Among the guests are 2020 National Book Award fiction winner Charles Yu and longlist nominee Megha Majumdar. The Common is pleased to reprint a short excerpt from Yu’s novel Interior Chinatown here.

Join Megha Majumdar and Charles Yu in conversation with host Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint (visiting writer at Amherst College) on Friday, February 26 from 7 to 8pm.

Register and see the full list of LitFest events here.

This interview is the fifth in a new series, Writers on Writing, which focuses on craft and process. The series is part of The Common’s 10th anniversary celebration.

This interview is the fifth in a new series, Writers on Writing, which focuses on craft and process. The series is part of The Common’s 10th anniversary celebration.