By CARLA ZANONI

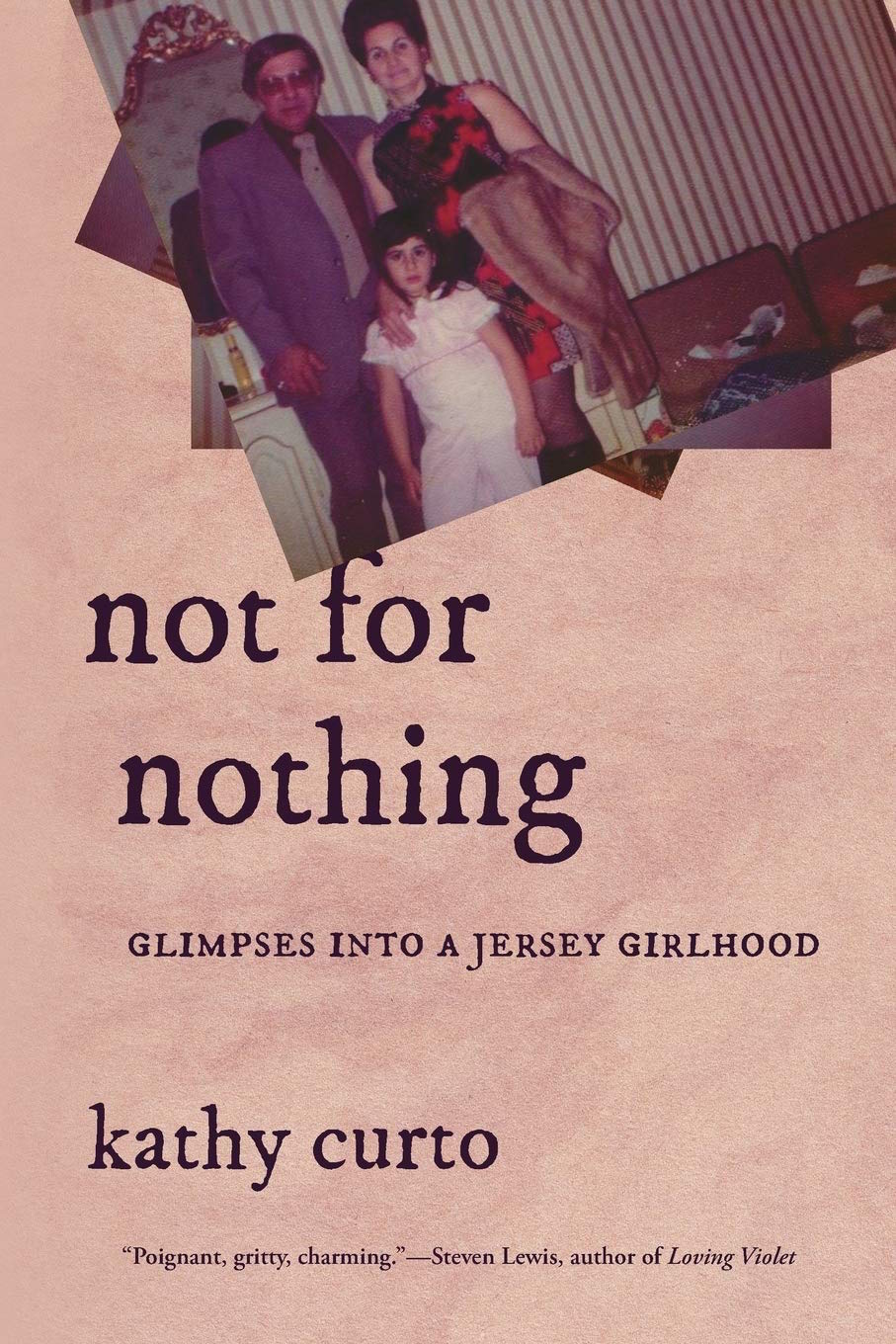

Kathy Curto’s memoir, Not for Nothing: Glimpses Into A Jersey Girlhood, is a dynamic and bittersweet retelling of the author’s childhood in which she seeks to understand and reconcile the inner workings of her family while lifting the veil of the American dream. The book, Curto’s first, is told through a series of 52 loosely-connected humorous and poignant vignettes. It takes a close look at her Italian-American family, from behind closed doors as well as in the eyes of the southern New Jersey community around them.

Curto conjures moments from her early life like a carousel of sepia-tinted images brightly projected on a wall. Here is a moment of young Kathy dancing in a frilly dress atop her father’s gas station counter, lavished in accolades as she passes a customer with “yellowbrown” fingernails a soda. Here is Kathy making up stories in her head about the people whose socks and panties she folds while helping at one of her mother’s many jobs after they flee the home where they lived with her father. Here is Kathy discovering her parents sleeping naked on their bed after they reconcile, wondering why her mother’s buttocks look so white against her father’s browned and dirty hands, thinking, “I wonder if he’ll ever get his hands clean.” Here is Kathy fetching a silver lighter for her father at the family dinner table after she and her mother return home. With each Kathy we begin to put together the family’s story through this collection of brief and ordinary but compelling recollections.

Curto’s changing view and perspective as she comes of age from 5 to 19 is marked by her descriptions of once-glimmering scenes of domesticity, which are later rendered dull as she gets older and begins to understand her parents’ complexity in greater context. She introduces us to a medley of characters, most importantly her immediate family, sketching them as if in a dream: shining a light on some and leaving others in the shadows. Yet, when we look closer at the stories Curto tells, a greater theme of work, labor, and money appears.

Set in the 70s, Not For Nothing is a coming-of-age story that takes place in the wake of the passing of the Hart–Celler Immigration Act of 1965, which marked a major shift from earlier U.S. immigration policies. Whereas naturalized citizenship had previously been limited to those deemed “white persons,” focusing the bulk of naturalization rights on persons from three countries — the United Kingdom, Germany, and Ireland — Hart-Celler removed such restrictions and established a policy based on reuniting immigrant families and attracting skilled labor.

The shift created new opportunities for Italian-American families who had long suffered racist, oppressive, and often dangerous discrimination in the country. It also left that generation with the burden of assimilation, creating pressure on families to “make good” on their opportunity by abandoning their heritage, language, and culture in order to fit in and move up economic ladders and within the American caste system.

Curto’s story is thus one that is caught in a moment of cultural transition. In her epilogue, she notes that she tried to write without the pretense of “analysis or psychobabble” or the intention of telling the definitive story of her Italian-American family. Instead she allows the mosaic of scenes to hint at the tension of her experience.

Her father Freddy owns several gas stations where he works long hours and spends most of his time tending to customers. He is treated like a king at home, his daughter and wife laboring to meet his every need with the weight of machismo hanging over their roof. Freddy pays for his expensive toupees in part by giving his barber Leo free oil changes and regular family meals made by his wife. Kathy says it “probably made him feel like a big shot and he probably loved it when Leo said, in front of all the customers, ‘Freddy, I’m telling ya. That wife of yours, she could make meatballs outta cardboard.’”

Freddy’s shiny suits and toupee seem intended to show the world he’s a successful American, not just fresh off the boat. The family spends vacations down the shore or at Mt. Airy Lodge in the Poconos, where Curto’s mother filches towels and ashtrays. Christmas holidays are spent driving to New York City to see the Rockettes and St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and to have dinner at Patsy’s. Her dad doesn’t brag about their outings, but is constantly voicing his concerns about how others see him—the white neighbors who live next door, his wife’s family. Despite the show, young Kathy knows exactly what her family is not: “We’re not a white-picket-fence-Apple-pie-family.”

Curto’s parents further come alive through precise and sharp dialogue that both delivers insight into their personalities and seems to offer the reader a chance to forgive them for their sometimes unsophisticated words and actions. “I’m no stunad,” her father says, in a flare of jealousy about an Irish neighbor “having the hots” for Curto’s mother. This comes mere moments after he slams an immigrant family for still speaking Italian at home (“If they made the decision to come to America…they should speak English.”). “Oh, Freddy,” says Curto’s mother, “for God’s sake, don’t be such a wise guy.”

Curto also describes family disputes hidden from neighbors between the two doors to the house: “the wood one stays open all the time, except for when we go to bed or when there’s a big fight and somebody slams it.” As Curto’s mother, whose name we never learn, comments, “no one knows what goes on in other people’s houses. Behind closed doors. Remember that.”

In one poignant scene, Curto describes her mother juggling her roles as mother and wife. The smell of a rag soaked in white vinegar permeates the house as Curto’s mother cleans while wearing a torn and bleached three-quarter sleeve striped navy and white top that had once made her feel like Jackie O (that is, white American royalty).

“She looked beautiful the first time she wore it,” Curto writes, drifting off into a nostalgic memory of a night on the Jersey shore — her mother in her new top, wearing bright lipstick, her father in light green shorts, bags of red and black licorice — before returning to the harried scene of her mother wiping the top of her lip in exasperation and taking a call from Curto’s demanding father. Curto’s memoir documents all of this labor: her father’s, her mother’s, and her own, such as when she repeatedly fetches her father’s lighter or ashtray when he motions for it.

Themes of identity and appearance are interlaced throughout scenes in the book with characters sometimes aware—and at other times unaware—of how they appear to the world. In her prologue, Curto shares that her writing process for this book had everything to do with paying close attention to what mattered and what didn’t, eavesdropping on herself and asking the questions her father once asked of her: “Happy now? Satisfied? Are you finished? Who do you think you are?”

These questions and Curto’s stories made me think about my own upbringing in New Jersey in the 80s and 90s and what it means to be an American. What do immigrant families have to prove and why? Where does the demand come from that they must assimilate “enough” to be considered part of the culture?

As an Argentine-American immigrant myself, with Spanish-Italian roots, I still do not know the answers to these questions. The difference of just a decade between my upbringing and Curto’s meant that my family’s narrative focused more on our Italian background than our Argentinian roots, attempting to assimilate through a more recently-made palatable genealogy. Ultimately, my white-passing family was betrayed by my parent’s Argentine accents and my mother’s olive skin. We were called spics in the 80s in the working class white neighborhood where we lived and worked hard to blend in and make something out of ourselves, becoming “American.” Today, more than two decades later, I am still teetering between the elements of my complex identity: Italian, Spanish, Argentine, American.

In this time of racial reckoning, these questions feel even more urgent. Discrimination against Italians is recent in the US’s history, and yet largely a thing of the past due to assimilation. But the pathway of assimilation to tolerance to acceptance — in other words, who is permitted to assimilate and why is it necessary to assimilate– remains rife with problems, especially as we seek to reconcile the mythology of immigration and the reality of past history (including those Americans who were decidedly not immigrants and either had their land stolen or were forcibly stolen and brought to this land themselves).

That’s the thing about the title’s double negative, “not for nothing,” thought to have first been coined by Shakespeare in the Merchant of Venice. In using it, Curto lays claim to something very important: that the retelling of the stories of her childhood can help her understand the identity of her family and its place in this world.

“Not for nothing, but chumps like him, they got no respect for guys like me,” her father says of their white neighbor whose family’s property abuts their yard. “Who the fuck does he think he is?”

“They’re nothing like us,” Kathy tells the reader. “The whole family is tall and quiet. We’re short and loud.”

The vignette closes with Curto asking herself the same question she has attempted to answer throughout the whole book, “Who do I think I am?”

Carla Zanoni is an award-winning journalist, writer, poet and media strategist. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, TueNight, Modern Loss and various news publications. She is TED’s first head of audience development and is formerly of The Wall Street Journal, where she was the first Latina named to its masthead. She is a graduate of Columbia University’s School of General Studies and School of Journalism and is currently enrolled at the One Spirit Interfaith Seminary. Carla is also writing her first book, a memoir on self-worth.