Movie directed by BAZ LUHRMANN

Reviewed by

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 The Great Gatsby is a simple story at heart: poor boy meets rich girl and, by dint of superhuman perseverance, transcends his origins only to find out it doesn’t matter because her kind will never accept him anyway. This slender novel has become shorthand for the Zeitgeist of the Twenties. Its language is flowery, even hothouse, Fitzgerald’s voice lush. Yet, using a detached character as narrator, Fitzgerald knits atmosphere, recurring objects, patterns, and themes into an iconic drama about the ringing failure of the American dream and a contender for The Great American Novel. Australian director Baz Luhrmann’s new adaptation of Gatsby is the third major film version and, though this Gatsby is a fun ride, its emphasis on spectacle muddies Fitzgerald’s masterpiece.

Luhrmann merengued onto the scene with Strictly Ballroom, his wild movie about the extreme and eccentric world of dance competitions in small-town AustraliaSet featured image. As often happens, this talented director’s first film was the perfect vehicle, and subsequent subjects have been a tougher fit. I liked best his post-apocalyptic Romeo and Juliet,which had flashes of brilliance–Juliet’s bier lit by thousands of candles, Romeo’s first sight of her through an aquarium, the pool scene, and the incandescent performances of Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes. Luhrmann was famously faithful to Shakespeare’s text, which withstood his visual barrage. Romeo and Juliet, a play about the universal intensity of young love, doesn’t depend on place. Not so The Great Gatsby. Location is Fitzgerald’s forte. He writes about wealth and power through real estate.

A film director has a responsibility when adapting a classic to stay true to the vision of the book. I don’t think small changes matter; I welcome them if they make a movie work better. The best adaptations (The English Patient, The Talented Mr. Ripley) enhance the story so that its essence comes into focus through the camera lens and the interpretative powers of film. The hope is for a symphonic version of the book, where before it was a solo performance. Put another way, film offers the possibility of going from 2D to 3D (in a good way).

This Gatsby is 3-D all right—literally and figuratively. Luhrmann is not a subtle director. If you’re going to eat this cake, you’d better like a whole lot of icing. This isn’t the jazz age; it’s the jazz age on Adderall.

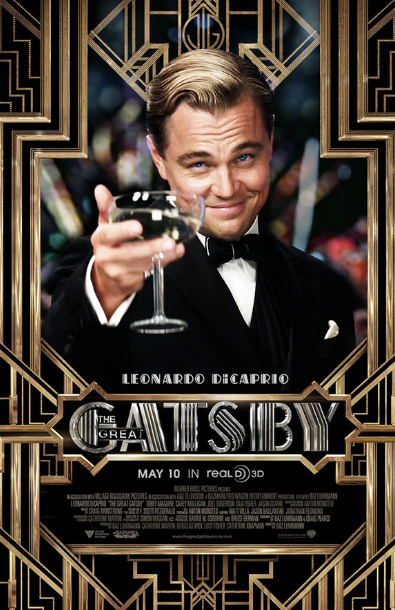

The movie is a visual riot, and a pretty damn pleasurable one: Leonardo DiCaprio in 3-D, snow falling all around you, butterflies and fireworks and dancers close enough to touch. But Luhrmann’s fawning attention to spectacle caricatures each place in the story, and that’s my main concern.

From one block to another in the same neighborhood, most of us are aware of the signs of success or failure that real estate gives off, even without the wattage of thatview or this pool. In Fitzgerald’s novel, East Egg is the old-money enclave where Jay Gatsby’s love, Daisy, and her husband, Tom Buchanan, live. West Egg, across Long Island Sound, is where Gatsby builds his palace, a new-money place in transition.

In this version, narrator Nick Carraway’s West Egg rental is homey as a hobbit house straight out of Tolkien. Gatsby’s turreted monstrosity of an estate next door (a mash up of McMansion, Scientology Headquarters, and yes, Snow White’s Castle) has all the taste of Disney with rows of oil paintings and Busby Berkeley dancers peeling off into the pool. The gardens of Daisy and Tom Buchanan’s East Egg spread are curiously reminiscent of Versailles, while the Valley of Ashes looks like something out of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. All this is so Vegas-y, so over the top, so Jay Z (who’s an executive producer and responsible for the sound track), that the nuances of wealth get all mushed together.

If East Egg is as lurid as West Egg, what’s the point? Colorized grass and crenulated houses come at the expense of credibility. Would Daisy, well bred as she is, really go for this Vegas across the Sound? Why does her house scream Kardashian if she is a Louisville debutante? And why doesn’t any of this look remotely like moneyed Long Island?

In a nation of immigrants, most wealth is relatively new. Yet we’ve created our own dynasties of Haves and Have-Nots. The nuances of wealth are Fitzgerald’s primary interest, as epitomized by West Egg and East Egg and the Valley of the Ashes, and it’s important that Baz Luhrman get that right.

Fitzgerald had an upper-middle-class upbringing. He also went to Princeton and married a debutante. He knew wealth from the perspective of someone who had entrée, though he struggled with money problems all his life. Nick Carraway is exquisitely sensitive to the ins and outs of money. But what we’re seeing here isn’t Fitzgerald or Nick’s point of view, it’s Luhrmann’s. This director gives us wealth from the outside looking in, and that’s the problem. He’s too childlike, too impressed, too voyeuristic, and his Gatsby ends up looking like a steroid-enhanced episode ofLifestyles of the Rich and Famous or The Bachelor.

Luhrmann also takes pretty big liberties with plot and form, some more successful than others. He frames the story as written by Nick in rehab, a move that adds zero to the narrative. In a more fortuitous change, Luhrmann excises the character of Michaelis, the coffee-shop owner in the Valley of the Ashes who talks to Myrtle’s husband, George, after she is killed in a car accident. This actually strengthens the story because Daisy’s husband, Tom, ends up being the one who suggests to George that Gatsby is responsible for Myrtle’s death. George then shoots Gatsby.

Luhrmann makes another significant change at the end. In the book, Gatsby is abandoned by Daisy and shot in his pool. In Luhrmann’s version, the phone rings, and Gatsby leaps to the conclusion that it’s Daisy, just before he’s shot. Nick says that Gatsby is the most hopeful person he’s ever met. This shift lets that hope live.

In the face of Luhrmann’s stagey direction, only DiCaprio’s performance cuts through the overkill. His finely calibrated Gatsby gives us the man’s painful contradictions in detail after detail: the compulsive smoothing of his hair, the tight crossing of his legs, the royal wave, the fastening of that high suit button as if rearranging himself into a more correct version, as well as hints of brutality in his hushed asides with the gangsters who always seem to be just off-screen. The other actors try their best, but seem unable to transcend the stylized movements, the clipped dialogue, and the frenetic dance of the camera. If this movie has heart, it belongs to DiCaprio.

In a 1922 letter to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, Fitzgerald wrote that he wanted to create “something new—something extraordinary and beautiful and simple and intricately patterned.” In this version, you can check off extraordinary, beautiful and intricately patterned if not simple.

I admit to enjoying Luhrmann’s candy-box aesthetic. Watching the film is kind of like eating that box of violently colored meringues, knowing they’ll make your teeth ache. I just wish Luhrmann had been more willing to take a back seat to the author. He obviously respects Fitzgerald’s intention. In chats on his website, he talks about “making the best version of Gatsby for our time.” He lists a long string of research books, worthy of a doctoral scholar. His home page features a coat of arms bearing the motto: “A life lived with fear is a life half lived.” Fear of what? That he’d mess up this book? That fear might have been a good one to keep.

Lisa Alexander is a writer living in Los Angeles. Her fiction has appeared, among other places, in Cimarron Review and won the UCLA James Kirkwood Award in Creative Writing. She was nominated for an Emmy for executive producing a mini series adaptation of The Mists of Avalon.