Curated by PAMELA RUSSELL and SHEILA FLAHERTY-JONES

Sidney Waugh was a twentieth-century sculptor best known for architectural and large-scale works on the one hand, and for smaller designs for glass and medallions on the other. As lead creative artist at Steuben Glass in New York, he elevated glass to a fine art medium, while also designing many public and private monuments on the East Coast of the United States. Waugh worked in a style typical of the 1930s and 1940s that owed much to the Art Deco aesthetic, emphasizing symmetry and simple, linear forms.A good example of Waugh’s architectural sculpture is the noble, forthright Apollo in the pediment above the entryway to the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College (see photo). The Mead holds a wide range of works by Waugh, in glass, plaster, marble and bronze, including study models as well as examples of his best finished work.

Mead pediment.

Draped in a cloak with stiff, symmetrical folds recalling Greek Archaic sculpture, a rigidly frontal Apollo turns his head toward his lyre. The curvilinear volutes and acanthus fronds below provide a welcome counterpoint to the god’s severity.

Toward the end of World War II and in the years immediately following, Waugh took part in the heroic international effort to track down the masterpieces and monuments looted by the Nazis during the Third Reich, and to return them to their rightful owners—museums, governments, and private collectors throughout Europe. The retelling of this chapter in history will soon draw audiences to theaters, when Monuments Men, directed by and starring George Clooney, opens on February 7.

Sidney Waugh, Lord Jeffery Amherst, 1936, bronze maquette, AC 1964. 5.

In 1956 this bronze model of a never-realized equestrian statue of Lord Jeffery Amherst was cast from a deteriorating 1930s plaster version through the efforts of the Mead’s first director, Charles Morgan. Waugh and a group of Amherst College alumni were at one point eager to commemorate the British general in a large-scale statue to be erected on campus.

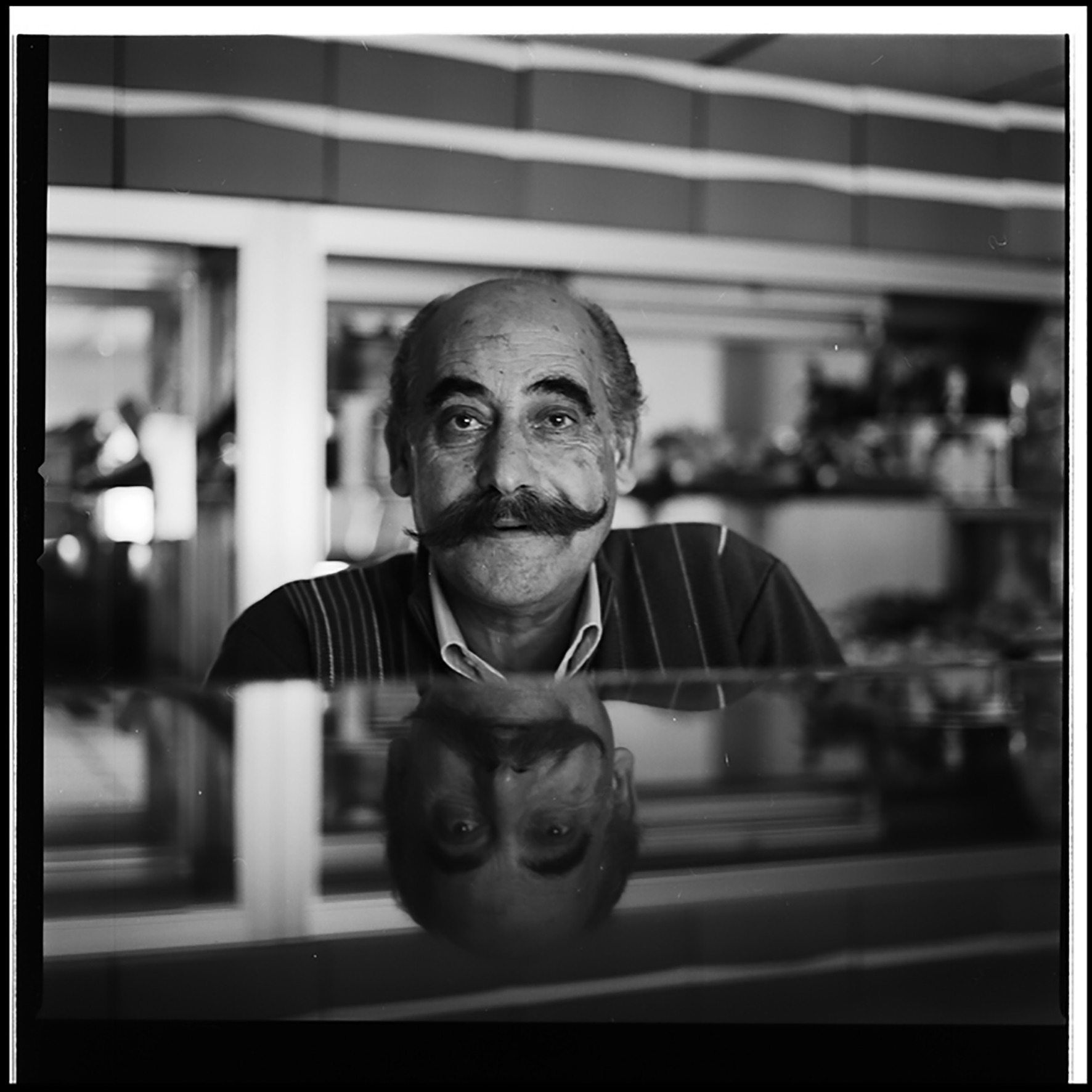

Sidney Biehler Waugh was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on January 17, 1904. He studied briefly at Amherst College, then attended the School of Architecture at MIT in Boston. In 1925, he went abroad to study, taking part in Salon exhibitions in Paris in 1928 and 1929. He was awarded the prestigious Rome Prize in 1929, which allowed him to study and use studios at the American Academy in Rome and to travel in Italy, France, and Sweden.

Though he returned to the United States in 1933, World War II sent Waugh to Europe again, as well as North Africa, where he served for four years in the U.S. Air Force. He was one of approximately 345 men and women from 13 countries working in the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives (MFAA) program of the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied Armies, charged with protecting Europe’s cultural treasures from looting and destruction.

Sidney Waugh, Buffalo, 20th century, bronze sculpture, 9 x 11 15/16 x 3 7/8 in, AC 1981.18.

Waugh emphasizes the strength of this quintessentially American beast in the simple, almost abstracted form of its great body and powerful forelegs. Only the lowered head is rendered with any detail.

The MFAA is credited with locating and returning more than five million monuments and works of art. The largest MFAA discovery was the salt mine at Altaussee, Austria, that had served as a Nazi repository for thousands of works of art, including the Van Eyck brothers’ Ghent Altarpiece, Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, and The Astronomer by Vermeer. For his part in the war, including MFAA missions carried out under fire, Waugh received the Croix de Guerre twice, as well as the Silver Star and the Bronze Star. He was also named a Knight of the Crown of Italy.

After the war, Waugh resumed his career in New York City, where he had started in 1935 as chief associate designer for Steuben, the art glass division of Corning Glass Works. A few years earlier, in 1932, Steuben chemists had developed a brilliant new glass “of such high refractive quality that it permitted the whole spectrum of a lightwave (even ultraviolet) to pass through.” Waugh pioneered methods that turned the sparkling clear, crystal-like glass into modern designs of remarkable grace and elegance that characterized Steuben pieces for the rest of the 1930s and 40s. He spent the remainder of his career at Steuben, and his works in glass were highly sought after by collectors. President Truman selected Waugh-designed Steuben glass bowls as a wedding gift for Princess Elizabeth (now Queen Elizabeth II) in 1947, and as a gift for Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands in1948.

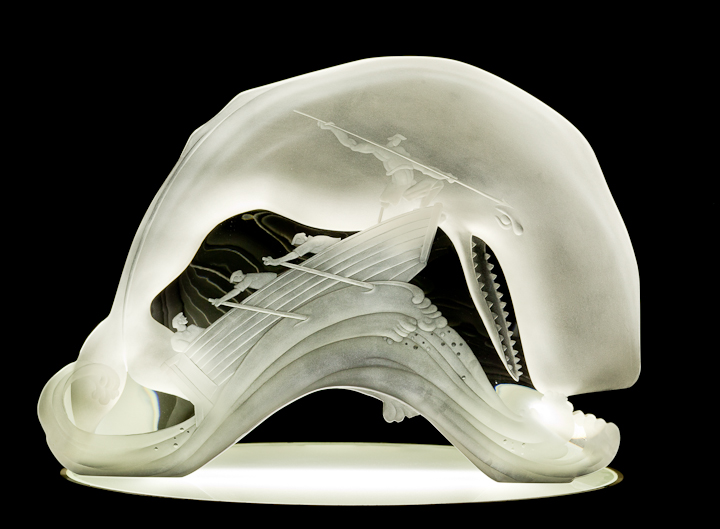

Sidney Waugh and Donald Pollard, Moby Dick, 1959, glass sculpture, 11 1/4 x 8 1/4 in, AC 1964.50.

Designed to be dramatically lit from below, this compact yet action-packed sculpture captures the high drama of Captain Ahab’s revenge on the great white whale.

Waugh’s stone sculpture owes much to the ancient art of Egypt, Greece, and Rome, and exhibits similarities to the earlier work of noted American artist Paul Manship (1885–1966), also a Rome Prize winner. His style—modern, but not threateningly so, and rooted in the great civilizations of the past—was favored for important civic commissions. His designs appear on several government buildings in Washington, DC, including the National Archives, the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Trade Commission and the Environmental Protection Agency (formerly the U.S. Post Office Department). Other well-known examples of Waugh’s public sculpture include the Mellon Memorial Fountain near the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the monument to General Casimir Pulaski, hero of the Continental Army during the American Revolution, in Philadelphia.

Sidney Waugh, Horse’s Head, 1934, plaster, 13 x 7 3/4 x 6 1/4 in, AC 1964.60 (view 2)

The cog-like mane seems to hold a vise-like grip on the energies of the resisting horse—a metaphor perhaps for industrial mechanization’s hold on the human imagination?

Sidney Waugh, Swedish Woman, 1932, plaster bust, 18 x 15 7/8 x 10 3/8 in,AC 1964.59b (side view)

The simple oval shape of this woman’s head, the regular, repetitive strands of hair, and the closed eyes lend a haunting, calm serenity to this elegant portrait.

Sidney Waugh died in 1963, at the age of 59. His works are in the collections of major museums, including the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and have been exhibited internationally. The Mead’s Waugh collection consists of around 50 works, in addition to many sketches and drawings.

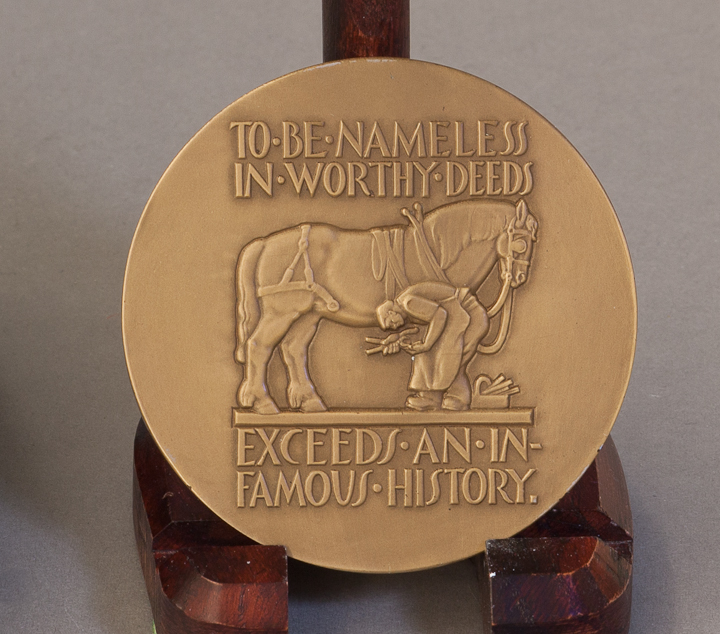

Sidney Waugh, To Be Nameless in Worthy Deeds, n.d., bronze medal, 3/16 in x 2 7/8 in,AC 1964.37.

Reminscent of the Cowardly Lion’s award for bravery, this medal rewards the valuable achievements of the heroic Everyman.

Pamela Russell is the head of education and the Andrew W. Mellon curator of academic programs at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College and the vice president for outreach and education of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Sheila Flaherty-Jones is the curatorial and editorial assistant at the Mead.