Artist: TRAVIS MEINOLF

Curated by ELIZABETH ESSNER

Travis Meinolf, Fabric panels made for with Kai Althoff, Whitney Biennial, 2012

If you need a blanket, Travis Meinolf, the self-appointed Action Weaver, will give you one. For free. And it won’t be a common fleece or wool number. It will look like folk art. It could be made by the artist or by many hands, and perhaps strung together from woven cloths of varying stripes, colors, and sizes. These free hand-woven blankets are a component of the artist’s ongoing project Blanket Offer, part of the artist’s grand mission to bring weaving to the masses.

Weaving—creating fabric on a loom with interlaced threads of warp and weft—is often thought of as the exclusive purview of grandmothers and aunties, and as such is often overlooked and undervalued. The artist did inherit his first loom from his Wisconsin grandmother, but Meinolf refutes the pejorative idea of weaving as “women’s work” and positions the craft as something far more powerful: a political act. Meinolf frames his activism within the larger history of textile production as a driver for social change. While the mechanization of cotton cloth production fueled the industrial revolution in nineteenth-century Britain, the artist points to the other side of social change: Mahatma Gandhi’s call to take back regional cotton production in India and the boycott of British cloth during the American Revolution.

Travis Meinolf, Communal Digital Tapestry, 2010

Born in Marin County, California, Travis Meinolf studied industrial design at San Francisco State University, where he took up weaving as an antidote to the aesthetic rigors of his program. By the time he entered California College of the Arts for his master’s degree, he was focused on fiber and received an MFA in textiles and social practice. Today, the Action Weaver lives and works in Berlin, heading up a small, free weaving school, teaching in museums and schools, and making his own pieces as a public textile artist.

Meinolf’s work can be placed in the context of what the seminal artist Joseph Beuys deemed ‘social sculpture’—art’s ability to transform society. Seeing the world as a holistic work of art and each person in it a creative participant, Beuys pushed for the interconnectedness of art, politics, and life. Meinolf puts this view into daily practice.

Collectively woven blanket organized by Travis Meinolf, The Weaving Place, Vancouver Art Museum, 2008

By teaching weaving, Meinolf links people directly to the things they consume: the clothing they wear, the upholstery they sit on, the curtains they draw at the end of the day. Unabashedly utopian in his vision, Meinolf wants us to consider slow production over quick, highlighting the rapid and poor conditions under which cheap products are made. Yet, he does not preach; he lets the immediacy of learning to weave do the converting. Gentle and inviting, the artist encourages anyone interested to participate in the thrill of creation, the sensuality of touching handmade cloth by illuminating the process under which it was made. In Mienolf’s MFA thesis, Common Goods, also published on his website, he imagines a “true gift economy” where people can learn new skills and take what they need without the constraints of money.

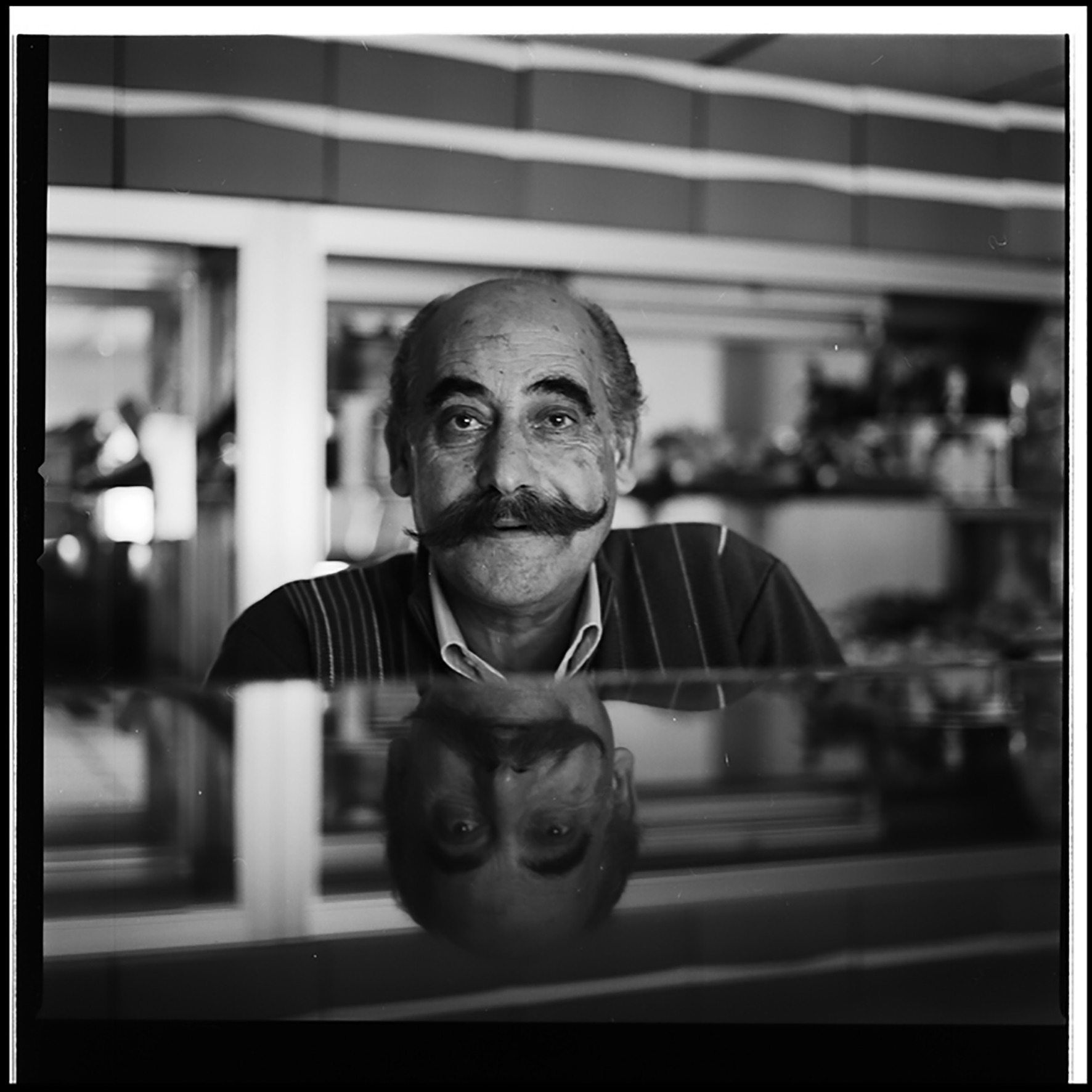

The Action Weaver on the streets of Berlin, 2010

To invite people into the process of weaving, Meinolf brings his loom to the street, literally. Under the ongoing performance piece Social Fabric, the artist drags a floor loom roughly the size of a small piano and retrofit with wheels to parks and street corners in Los Angeles, Milan, Oslo, New York, and elsewhere. Then he simply weaves, sharing the process with whoever is interested. Part tutorial, part performance, and sometimes part party, the artist allows the public access to an unfamiliar process, despite the universality of its product: cloth.

When I first saw a photograph documenting the artist’s street weaving, it was a radical image—the giant loom, the peaceful look on Meinolf’s face amidst the flurry of urban commotion surrounding him. Pedestrians were clearly taken in by the public display, but it was hard to tell what was behind their glances. Meinolf details people’s differing reactions to his work – everything from annoyance to active interest. During Social Fabric, many have chosen to spend time weaving with the artist. In fact, some people even incorporated bits of cloth and wool from their clothes into the fabric to document their involvement.

Action Weaver, Travis Meinolf wheels his loom, Berlin, 2010

Public participation is key, but weaving generally requires extensive equipment. In response, Meinolf has pioneered an inexpensive laser-cut plastic loom, which he supplies to anyone who asks, either for barter or for free. Its design is based on a primitive backstrap loom. To create a piece of fabric, little else but yarn and something to tie it to, in order to create tension, is needed; Meinolf has encouraged his students to use a tree, bookcase, or even another person. But, one need not even acquire a loom from the artist; he offers a free internet tutorial (one of many) in which one can create a tiny loom with two 3 x 5 note cards and a pencil.

Action Weaver, Travis Meinolf demonstrates at Weavolution, Coventry, UK, 2011

Not all of Meinolf’s artwork is in the public sphere. The Weaving Place, Meinolf’s first show, was at the Vancouver Art Museum in 2008. The artist set up small, easy-to-use looms, and, under his direction, over one thousand people tried weaving. The resulting fabric was sewn into blankets, which participants then decided should be donated to the local homeless population. These blankets move beyond pure function. Each person’s learning process is clearly illustrated in the fabric–‘community portraits’ are how Meinolf refers to them. One can imagine the recipient appreciating not only the physical warmth, but also a certain tenderness as these blankets capture the human touch.

Travis Meinolf, Fabric panels made for with Kai Althoff, Whitney Biennial, 2012

Since then, Meinolf has hosted countless weaving picnics, parties, and even an Olympics-inspired weaving race in Manchester, Britain. Collaborating with German artist Kai Althoff for his installation at the 2012 Whitney Biennial, Meinolf made shimmering woven panels that served as fabric walls for Althoff’s enigmatic paintings. He has also created upholstery fabric for the German furniture designer Max Lamb as a part of the 2011 London Design.

Spanning both public and private and materials both ordinary and fine, Travis Meinolf lives a life that is both theory and practice. As a catalyst for change on the grandest scale, he depends on some of the most humble things: human interaction, thread, and loom.

Travis Meinolf is the Action Weaver, a public textile artist, living in Berlin.

Elizabeth Essner is a design specialist living in Brooklyn.