This piece is excerpted from the novel We Were Pretending by Hannah Gersen, a guest at Amherst College’s eleventh annual literary festival. Register and see the full list of LitFest 2026 events here.

This piece is excerpted from the novel We Were Pretending by Hannah Gersen, a guest at Amherst College’s eleventh annual literary festival. Register and see the full list of LitFest 2026 events here.

HANNAH GERSEN is a novelist whose fiction ranges from the strictly realist to the gently speculative. Her first novel, Home Field, is a deeply felt story about family and grief in rural Maryland, described as Friday Night Lights meets My So-Called Life. Her second, most recent novel, We Were Pretending, leaps into today’s most pressing crises–climate change, the creep of technology–through the lens of Leigh Bowers, an at-sea single mom trying to secure a better future for her daughter and a better death for her mother, who is dying of cancer. It’s beautifully written, imaginative, and elegiac with surprising twists and turns.

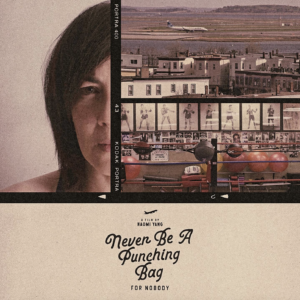

Film by NAOMI YANG

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

Sometimes visiting a new neighborhood can change your life. While scouting locations for a fashion shoot, filmmaker Naomi Yang happened upon a boxing gym in East Boston. The modest second-generation family business, with its sparring ring and wall of framed black-and-white photographs depicting local boxers, seemed like a great backdrop. Unfortunately, the gym’s owner and head coach, Sal Bartolo, Jr., disagreed, citing aprevious photo shoot that had gone badly, with high heels destroying his mats. There would be no fashion shoots in his gym. Instead, he gave Yang his pitch to all visitors, telling her to come back for a free boxing lesson. In voiceover, Yang confides to us that she did not take the offer seriously and didn’t plan to return. And yet, a few weeks later, she did. Part of her was holding out hope that Bartolo would change his mind. But another part felt drawn to boxing, and Bartolo’s gym would soon become the center of her life. Yang’s documentary tells the story of how this chance meeting at a boxing gym brought her into a deeper understanding of herself, and of the ways bullying forces can leave their mark on places as well as people.

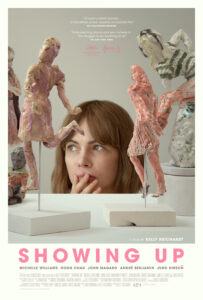

Film by KELLY REICHARDT

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

The art critic Jerry Saltz peppers his Twitter feed with advice to artists. Recently, he wrote: “Artists: Every single second you spend on being jealous of someone else is a complete waste of life.” Reading it, I thought of Lizzy, the sculptor at the center of Kelly Reichardt’s new film. Showing Up is a dry comedy that is a love letter to anyone who finds time to make art while holding down a day job and trying not to let anxieties—which might arrive in the form of jealousy, resentment, or self-loathing—get the best of them. What makes this story unusual is that it focuses on an artist in mid-career, someone who has honed her talent and is respected by her peers, but who is not famous or conventionally successful. I can think of a lot of movies about artists at the beginning or end of their careers, charting the exciting rise or the tragic crash-and-burn, but there aren’t many filmmakers who can find the drama in the daily life of an artist diligently doing the work.

Film by MIA HANSEN-LØVE

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

In middle age, many women find themselves members of the sandwich generation: those who are caregivers to both their elderly parents and young children. Such is the fate of Sandra Kienzler (Léa Seydoux), the heroine of Mia Hansen-Løve’s sneakily powerful drama. Set in Paris, Sandra’s story also unfolds in the busy landscape of midlife. She’s both a widowed mother to her school-aged daughter, Linn, and a dutiful daughter to her elderly father, Georg (Pascal Greggory), who is suffering from Benson’s Syndrome, a rare, neurodegenerative disease. In the film’s opening scenes, we see Sandra hurrying from work to visit with her father before picking her daughter up from school. It seems she’s figured out a way to balance everything, but it’s also clear that it can’t last. Georg can no longer open the door without coaching from Sandra or prepare food for himself without help. His disease affects his vision and his memory, and Sandra has to remind him that she works as a translator, and that his favorite author is Thomas Mann. A former philosophy professor, Georg lives alone in an apartment filled with books he can no longer read. He survives thanks to visits from his daughters, Sandra and Elodie, his ex-wife Françoise, and his long-term girlfriend, Leila.

Much of One Fine Morning is concerned with Georg’s decline, and the struggle to move him out of his apartment and to find affordable long-term care. This process is long, drawn-out, and extremely sad for everyone involved. But it’s not the only dramatic thing happening in Sandra’s life: she’s also falling in love with an old friend, Clément (Melvil Poupaud), a married father whose son goes to school with her daughter Linn. It’s Sandra’s first serious relationship since her husband’s death, and it’s immediately intense. The convergence of these two psychically seismic events is what give One Fine Morning its dramatic shape, but it’s the attention to Sandra’s daily activities which gives it a texture that feels remarkably true to life. Sandra may be in a difficult transitional period, with big emotions roiling underneath the surface, but she still needs to get on the bus and head to work; she still has to pick up her daughter from school; she still has to plan for vacations, celebrate holidays, and figure out what on earth to do with all of her father’s books.

Documentary filmmaker Alice Diop brings an unsettling sense of reality to her first fiction feature, which follows a novelist attending the trial of a woman accused of drowning her 15-month-old child. Based on a real-life incident of infanticide, the courtroom proceedings depicted in Saint Omer borrow from the 2016 trial of Fabienne Kabou, which Diop herself attended. In synopsis, this may sound like a lurid mix of fiction and documentary, but this precise and emotionally complex film, which sprung from Diop’s fascination with Kabou’s trial, does not have the anxiety-stoking energy of a true-crime story. It is so rooted in the point of view of Rama, the writer attending the trial, that I hesitate to describe it as a courtroom drama. The film’s dual focus—on both Rama, the writer, and Laurence, the young woman accused of infanticide—turns the trial into something other than pure spectacle and results in a story that looks closely at the frighteningly powerful bond between mother and child.

Film by SARA DOSA

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

You don’t expect a documentary about volcanos to begin in freezing temperatures, but in the first scenes of Sara Dosa’s enthralling new feature, Fire of Love, married volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft struggle to free a jeep mired in icy slush. Farther down the road is a fiery pool of molten lava. Much later in the film, they trudge through the gray ash of a recently erupted Mount St. Helens, a setting that looks cold even though it is baking hot. Both landscapes seem unreal, even with Maurice and Katia in the frame. Their footage is so remarkable that I would have watched a 90-minute slide show of their photographs. Fire of Love is much more than that, but the film and photo archive is at the heart of the story, and it’s where Dosa looks for clues as she tells the story of the Kraffts’ career, one that was inseparable from their romantic partnership.

Film by EMELIE MAHDAVIAN

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

In recent years, female filmmakers have been carving out a space for themselves in the American West, redefining a genre and a place that is has historically been depicted as the terrain of lonely male cowboys and vigilantes. There have been period pieces like Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, and Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff and First Cow, as well as contemporary stories set in the west, such as Chloe Zhao’s The Rider and Nomadland, and Reichardt’s Certain Women. These films bring a new realism to the western as they widen the lens to center female characters and to incorporate themes of friendship, romance, and community.

Film by CÉLINE SCIAMMA

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

Petite Maman, Céline Sciamma’s fifth feature-length film, following 2019’s critically acclaimed Portrait of a Lady on Fire, is a time travel story that reminded me of one of my favorite movies from childhood: Back to the Future. Aesthetically, the two have very little in common—one is an art house movie with unknown child actors, the other a somewhat goofy studio feature starring Michael J. Fox—but at the narrative core of both films is a deep psychological wish that many children harbor: to know their parents when they were younger. In Back to the Future, a teenage Marty McFly accidentally travels back in time to meet his parents at the beginning of their high school romance. In Petite Maman, eight-year-old Nelly stumbles into a kind of woodland passageway through which she can visit her mother’s childhood and play with her mother as an eight-year-old girl. In this alternate reality, Nelly also interacts with her maternal grandmother who, in Nelly’s present-day timeline, has recently passed away.

Film by IULI GERBASE

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

A title card at the beginning of Iuli Gerbase’s debut feature, The Pink Cloud, informs viewers that its screenplay was written in 2017, and that it was filmed in 2019. What follows is a movie so in tune with the events and moods of 2020 that you would be forgiven for finding this level of prescience impossible to believe. The premise is simple: a toxic pink cloud formation suddenly appears in the sky. Its vapors are deadly, killing people after ten seconds. With only a few minutes of warning, an unnamed Brazilian city is locked down. People are ordered to go indoors immediately; if they are not at home, they are to go into the nearest building, whether it’s a bakery, a grocery store, or the apartment complex they happened to be passing by. Giovana and Yago, the couple at the center of the movie, are on the balcony of Giovana’s apartment when they hear the news, recovering after a late night of partying. We quickly learn that they don’t know each other well; they are waking up from a one-night stand that has been extended indefinitely.