By RAVI SHANKAR

1.

Tomorrow is Amma’s seventieth birthday, and I’m wondering what to buy her. She’s told me that the only thing she wants from her children is a new toilet seat, a pair of sensible black shoes, or a replacement floormat for her decade-old Honda Civic. None of these gifts seem particularly appropriate to such a consequential birthday, but then again, Amma has always been practical. When she tells the story of her arranged marriage to my father at nineteen, a decade younger than this man she had only met once before, she recalls bringing a griddle and leaving behind stamp albums as she embarked upon a permanent journey from her home in Coimbatore, South India, to Northern Virginia.

Though she would never see it this way, my mother’s is the story of a woman born into a patriarchal society, considered property, and consigned to do the bidding of men. By all accounts, including her own, she had been blessed with an ideal childhood. After Madras, Coimbatore is the second-largest city in the Tamil Nadu, a place sometimes referred to as the Manchester of South India because of its many factories and industrial heritage, but also with a slightly derisive edge. Nearly half the motors, water pumps, and wet grinders in India are manufactured in this city, though little of the music or culture of its British counterpart.

Amma was the third of four children, and her father, my Thatha, or grandfather, was a journalist who worked for the PTI (Press Trust of India), which used to be Reuters, and provided news to all of the national newspapers. C.H. Krishnan wrote for The Hindu, India’s largest English-language newspaper, and there are photographs of him with Winston Churchill, Jawaharlal Nehru, and many other statesmen, cricketeers, and actors. He was stationed in Kashmir and East Bengal during partition in 1947, at which point the nation-states of India and Pakistan were created, and family lore has it that when violence broke out, he brought his family to safety in India and then smuggled himself back to the war zone, dressed as a Muslim woman shrouded in a head-to-toe burka. When I was growing up, Thatha was a larger-than-life figure, a charismatic, boisterous, roaring lion of a man who would have my sisters and me walk on his back to massage him and, even into his late eighties, meet us at the train station and insist on carrying all of our luggage by himself to a waiting taxi.

The apple of Thatha’s eye, Amma was a precocious student who was already working on a teaching degree by the age of nineteen, a sensitive artist who made watercolors of the surrounding villages, and a natural athlete who would spend languorous afternoons playing netball and riding her bicycle with friends to buy Indian sweets like mysore pak from the local marketplace before cooling off with a swim in the Noyyal River. She was a curious, deeply intelligent young woman, and surely marriage was the furthest thing from her mind when suddenly it was being proposed to her. Not by my father, but rather by her own, and “proposed” is probably the wrong word, too, since that verb implies choice.

Like many other Tamil Brahmins, or TamBrahms, as we’re sometimes known, my parents never flirted or dated, never enjoyed a friendship or the slow blooming of a romance, never got together nor broke up, never had premarital sex. Appa had already been in America for a few years and was nearly thirty when his own father thought the time was right for him to be married. Traveling through Kerala to check on some of the rice fields his family owned, my paternal grandfather stopped in Coimbatore on his way back home to see about a potential match. To be fair, it was Appa’s younger sister he had in mind, as finding a suitable union for a girl of marriageable age was always more complicated than finding a bride for a man, and he arrived at Thatha’s house to inquire about Amma’s older brother, my uncle Hari.

The two patriarchs of the family shared a cup of chai before dispensing with the small talk and heading to the local vedic astrologer in town, a wizened old lady who was functionally illiterate but who could read omens from palms and fates from tea leaves. She sat at a table with the two men and consulted her Vedic star charts, trying to pair up my aunt’s and uncle’s nakshatras (which are like zodiacal signs but more specific and ancient, being derived from the Rig Veda nearly five thousand years ago). Vedic astrology is an oracular language of divination, an esoteric reading of cryptograms that contain complex coded messages about each human soul. Matching my paternal aunt and maternal uncle together, the astrologer proclaimed that a marriage between the two would result in absolute disaster.

But ever-intrepid Thatha could not be so easily dissuaded; was he really going to let this eminent Brahmin gentleman from Madras walk away without a betrothal? Certainly not when he himself still had two daughters of marriageable age! So he insisted that they stay to try all the other possible permutations of his daughters, until nalla atirṣṭam! Good fortune! Amma and Appa were discovered to be a suitable match.

So it was written in the stars, and a handshake between the two men sealed the deal. When Thatha returned with the news that Amma was the one ordained to marry, her older sister, who surely, by the laws of propriety, should have been the one to marry first, stamped her feet in disbelief. Amma, unprepared for this news, was no happier; she ran barefoot from the cement house to climb the highest branch of the highest banyan tree in the yard, where she straddled a limb, sobbing. She couldn’t fathom the prospect of leaving behind her parents, her siblings, and her friends, the wide riverbanks and the tropical heat to travel across the world to live with a man whom she didn’t know in a place where it… snowed? It was unfathomable.

In the end, though, she had been raised to be the perfect daughter and would never do anything to displease her father. She had been raised to obey. And yet, when she met her groom- to-be for the first time, she refused to lengthen her hair with extensions or powder her skin to appear lighter. If he wouldn’t accept her as she was, she would have none of it. Thankfully—and perhaps regrettably, given that her very devotion to her father would be the event that would remove her from his presence for decades at a time—she was nineteen years old and gorgeous. Chaperoned by relatives, my parents met briefly and then quickly departed into their separate lives with the promise of their future nuptials hanging in the air like an omen. If they had been closer in age, would Appa still have felt like he had to keep his own inner life private from her and from all his children, demanding we never question him due to the dictates of his seniority and innate maleness? I sometimes wonder who Amma would be today if she had said no and married someone of her own choosing. Who I would be.

But they married each other.

Marriage of C.H. Krishnan and Parvathi Vaidhyanathan, Ottapalam (Kerala, India), August 1941.

Who knows what shy words they might have spoken in private for the first time? How large their early misgivings might have been? What their first nervous moments of intimacy were like? For when Amma tells us this story, it is often meant more as a rebuke for our stubborn willfulness than to bemoan her own fate. Her very life was proof of how much she had loved her own father and how she could scarcely have imagined challenging him. If she had been as disobedient as I and my two younger sisters sometimes were, she would never have been blessed with us three children.

“God works in mysterious ways,” she would say. If her voice quavered even the slightest bit for everything she had sacrificed, her future and ambitions, her free will, the shape of the life she might have led had she not been so suddenly uprooted, we could detect little of it as children.

There’s one photograph from their wedding ceremony that I particularly treasure: the two of them seated next to each other on an oonjal, or enormous swing; Appa, the maapillai, or groom, looking dashing in his suit, tie, and waxed pencil mustache, an abundant garland of jasmine flowers around his shoulders, and Amma, the bride, a lovely manamahal in a gilded sari with a nose ring and kohl-lined eyes, emanating both warmth and fierceness. If she was afraid, her eyes don’t show it. After Appa tied the mangala sutra, an auspicious necklace strung with black beads on a thread yellowed with turmeric, around her neck, and they had done the saptapadi, taking seven steps around the sacred flame, they were officially married. Appa left the next morning to return to America, with Amma following him there nearly six months later.

I’ve often imagined that journey, a near teenager leaving everything and everybody she ever knew behind, to travel with, yes, her griddle and her anjarai petti (literally a “five-room box,” a set of round tins in which cooking spices like mustard seed and masala powder could be stored) and her dowry of jewelry bundled in a parcel of handloom cloth which had been stuffed into a well-worn traveling bag, a hand-me-down from Thatha, who had also given her a crisp fifty-dollar bill to help her on her way. What ordinary courage it must have taken to traverse thousands of miles in a plane to live with this stranger, her new husband, in a foreign country. And, yes, her fears were confirmed: she landed in a snowstorm.

Appa was stuck in traffic, the roads to and from the airport ground to a standstill. When Amma would eventually deplane, there was no one there to greet her! Alone, cold, and terrified, she burst into tears by the baggage carousel and was consoled by a kindhearted Swedish Pan Am stewardess who sat holding her hand while Appa inched along in bumper-to-bumper traffic on the beltway in his rusty orange Dodge Dart, the chariot for his new bride.

Their fated arrangement is why I—an ABCD, or American-Born Confused Desi, as those in India like to mock us—am here, because Amma joined Appa in my uncle’s basement, trading her salwar kameez for a pantsuit so she could work packing turntable stereo parts in a factory while Appa finished his degree in mechanical engineering while also working as a part-time security guard in some of the least desirable neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. They saved up and sent money back to India. Eventually they would return home, bringing their children back to the source.

2.

Back in 1981 in Manassas, a Northern Virginia suburb known for the Battles of Bull Run and Lorena Bobbitt, I came home from playing touch football in the neighborhood park and was greeted with some grim news: Appa’s mother had been diagnosed with an advanced stage of colon cancer and as the eldest son, it was Appa’s duty to take care of her. Yet he had a job on the other side of the world, and so could not fulfill his filial duty. Instead, in the middle of my third-grade year, Amma told me that she and my sister and I would be moving back to South India, without my father, to take care of my grandmother. That’s what family duty entailed. No questions asked.

In a whirlwind that summer, my youngest sister yet to be born, my little sister Rajni and I were swept up with our suitcases and herded into the family’s aquamarine Chevy Nova to begin the long journey to Madras, the city where my father had been raised. Thinking now about my own daughters’ independence at the ages we were back then, I recall having no say in the matter, nor even the illusion that I might have had a say. No big goodbyes to my classmates, no sense of what the journey would hold. I do clearly remember tussling with my sister on the plane over a pair of plastic pin-on wings from the stewardess, as flight attendants were called back then. I remember drinking my first mini can of Coke on the plane. I was dressed in a military uniform with a peaked cap and a holster with a toy pistol that today would never be allowed in an airport, let alone admired by a flight crew.

We arrived at a cavernous, soiled airport where large rotary fans pushed heat from space to space. Numerous men in veshtis, the colorful cotton garments men wear tied around their waists in lieu of pants, jockeyed to carry my family’s bags. Appa firmly rebuffed them with a coarse brand of Tamil I had never before heard him use. The throng outside the airport, in its sheer mass and press of humanity holding signs and madly gesticulating, was terrifying. Yet somehow, even before my father seemed to find them, I recognized my extended Indian family, whom I had not seen in many years. I had been to India when I was six months and then three years old and had met some of these relatives in the U.S., so I felt enough of a sense of connection to wave wildly to them.

They waved back. A group of them stood together, all men, in short sleeves and Brylcreemed hair. They greeted us with backslaps and loaded us into an Ambassador taxi to take us back to my grandfather’s flat. The images of Madras at night are dusty and hallucinatory. I stood with my forehead pressed to the streaking taxi window while my sister sat with her hands clapped over her ears, for no noise I can now remember.

We slept on the floor of the small apartment in the large concrete building that first night, surrounded by our suitcases. In the morning, we were woken by koel birds and the cleaning woman who swept the doorsill with a broom made from a straw sheaf. My grandmother, even though she was going through chemotherapy, crafted an intricately looping and geometrically precise kolam with ground rice powder on her front stoop to begin the day with auspiciousness, and instead of Cheerios, I had a breakfast of idlis and sambar. Everything shone with marvelous new sounds and colors. Instead of waiting at the corner for the school bus, I sprinted to the rooftop with my cousins to play soccer and cricket. Our brown bodies glistening with sweat, we would weave and feint through the antennas and yards of colored cloth hung out to dry. Catching my breath, I wondered what would happen if I were to kick the ball over the parapet, and then considered for a moment where I was, so far from where I had come.

When I think back on first experiencing India as a child, my memories are clichés of exoticism and colorful holy tumult: throngs of Naga sadhus clad only in marigold garlands, chanting into the Ganges; each course of a thali served on a banana leaf that could be scooped into the mouth with the hands; naked children pissing outside of makeshift shantytowns formed of corrugated tin and cardboard; enormous, gaudy golden marriage halls blaring “Baba Ki Rani Hoon” into the night sky; an assemblage of previously unknown uncles, cousins, and siblings all sleeping together in a family bed.

C.H. Krishnan reporting on Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru for The Hindu, New Delhi, September 1946

“How can the mind take hold of such a country?” E. M. Forster asks in A Passage to India. “Generations of invaders have tried, but they remain in exile. … She [India] has never defined. She is not a promise, only an appeal.” Or, as Arundhati Roy would put it much later, “In India, the wilderness still exists—the unindoctrinated wilderness of the mind, full of untold secrets and wild imaginings.” Both condensations of the country are illuminative and problematic, for India is much more than an appeal or a signifier of an ancient culture, and what is wildness, really? From the standpoint of someone other than Roy, such a description would feel vaguely Orientalist; and yet those qualities of being variegated, numinous, and chaotic certainly differentiate the country, which cannot be captured in swift, turgid generalizations, mine or anyone else’s.

There was something so unspeakably innocent and startling about being in India, a culture where teenage boys strolled the streets holding hands or where the skies darkened with a downpour of fierce rain that might sop everything for weeks at a time. There are six seasons in India, the prevernal and monsoon added to the normal four.

I wish I had known back then how to hitch my star to India’s ratha, one of those oldest chariots in the world from the Rig Veda, and to talk smack back to the pimply-faced rat tail who had said my feet smelled like rotten curry on the school bus. Sanskrit slokas and Bollywood fight scenes had been a source of embarrassment to me. How do you talk to a white kid from Manassas about Vedic pride and the Ashoka Chakra? I wished that kid on the bus could have met my grandfather, who though seemingly ancient, was surprisingly strong and would engulf me in a bear hug each time I walked by the wood-and-rope Rajasthani chair in which he liked to spend his afternoons.

“Sorry for Kashmiris,” he would boom, his breath a mixture of clove and copper. “Nalla paiyaṉ uṭkāru! But India never invaded other country. We invented chess, algebra, calculus, surgery, navigation, zero, even your—how do you say?—Snakes and Ladders! Erumbu oorak kallum theyum! An army of ants can wear away the stubbornest stone.” While I tried to squirm free from his lap, he held me down tighter.

“Hippocrates? Ha! The wandering physician Charaka had consolidated the earliest schools of medicine known to mankind, Ayurveda long before the togas. Then we beat the Brits at cricket and found water on the moon.

“Never forget your roots!” he trumped before I was able to wriggle free to hide behind Amma. I was utterly unsure why we had traveled across the oceans to take care of my grandparents, for they seemed perfectly able to take care of themselves. How little I knew back then about how my grandmother was losing her hair and in constant pain. Nor did I have the knowledge or prescience back then to push back on my grandfather’s assertions; to bring up the Chola kings whose maritime adventures led them to occupy parts of Sri Lanka, how Punjab king Ranjit Singh annexed parts of Afghan territory in the early nineteenth century, or the fact that the border disputes between India and Nepal and Pakistan persist to this very day. I wish I would have known how the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the right-wing Hindu nationalist political party, would take power in India under the auspices of social conservatism and “Hindu values,” leading to the destruction of mosques, mob violence, and the disenfranchisement and criminalization of the country’s minority Muslim population. National pride is never complicated.

And at that age, Indian pride was just as foreign to me as the “Made in America” trucker caps and belt buckles that proliferated during the Reagan era in the U.S. or the red MAGA hats that show up at political rallies these days. Being neither Indian nor American enough, I tended to regard any outbreak of nationalism with a healthy dose of skepticism. Plus, I had been acculturated in the era of the grand melting pot, taught to liquefy those rich differences that prevented me from being a “true” American. To blend in. I never suspected that the act of folding those six seasons into four would carry its own trauma, because back then, the pressure to conform to an idea of Indianness while also trying to assimilate to life in Virginia had inverted; now I was in India as an American, and possessed with a sense of intoxicating adventure.

Since we had left America midway through the school year, I was almost immediately enrolled into the M.A.K. Convent, a bilingual school for the locals, where I was sent sweating in knee socks and myrtle green shorts held up with suspenders, swinging a tiffin carrier with Rajni, walking the two miles to school from my grandparents’ flat. I was a gangly third-grader, the youngest in my class by virtue of having skipped kindergarten. My sister was in preschool. I had just started acclimating to the American school system, so being uprooted to the motherland and made to take classes in Tamil in a dusty, ramshackle schoolhouse run by a stern headmaster and unsmiling teachers was not the best way to help me fit in. I found that the teachers had little tolerance for the novelty of me and my sister, the only two American transfer students, and that within a week of being in the school, we were expected to know all the rules, else face the repercussions.

Corporal punishment was a daily part of life at the M.A.K. Convent. It was meted out in the form of a swift ruler to the knuckles or a rough grain sheaf to the backside. Each morning, we arrived to sing “Tamil Thaai Vaazhthu” (“Praise for Mother Tamil”) and “Jana Gana Mana,” the Indian national anthem, before our classes began and we learned, by rote, multiplication columns enumerated in a journal and tedious entries about Indian independence copied out in English and Tamil in our composition books. Class participation was frowned upon, so unless you were called on, you kept quiet. The only time a little buoyant energy was allowed release was after lunch, when, under the watchful eye of teachers in austere blue saris, the girls plaited one another’s hair under the kattumalli, or cork tree, and the boys grappled in the yard and played cricket with a discarded desk leg.

From the first day there, I was challenged for my difference. For coming from America. For sounding like John Wayne, according to Mahesh, a mousy little big-eared boy with a uniform made threadbare by vigorous hand-washing. Luckily, weaned on a diet of pasteurized milk, peanut butter, and whole-wheat bread, I was bigger than him, bigger in fact than almost all my classmates, and though normally shy in America, I found I could go into beast mode here when I was threatened. Turned out I was a rangy dervish that the other boys could not bring down, much as they’d try to corral me in the yard, clutching at my suspenders or piling on top of me, screwing on my head and double-teaming me, derisively calling me the names of American pop stars and movie stars but never managing to rub my nose in the dust. At least not literally. Instead, after an afternoon of pursuing me, it was they who would routinely lie scattered around me like sacks of rice while I was the one to be scolded by a nun and pulled into the classroom by the ear, where I might have to spend an hour after school sitting on my knees on a desk. Begrudgingly, and due to brute force more than any commendable principle, my fellow students began to respect me.

Even back then, in third standard, there was a sense of the stratification of the classes, a kind of social inevitability about who would succeed and who would recede into the fields as a laborer, into the river as a launderer beating shirts on a stone, or under trays of sambar as a paan-stained waiter. The rural kids would dutifully take their punishment, even grinning through their grimacing as if they couldn’t believe their luck to be away from their family’s poverty and with other kids their age all day. So what if the nuns droned on, the lesson plans were soporific, and there was the occasional beating? No matter how the politicians stumped on about the caste system being dead, the rural kids were steamrolled into centuries of familial destiny.

Then there was someone like Vivek Mithranandran, whose father was a pediatrician and who wore distinctive bowties with his uniform, one embroidered in fine gold thread, another floppy and oversized, yet another made of satin or velvet. He was paler than the rest of the boys, almost like he had been powdered ever so faintly with some mysterious talcum. He looked slightly sickly, which would normally keep one away, yet I was compelled to get that much closer to him. I smelt the faint tinge of sandalwood and dusky lavender under his nails. He spoke with a stutter, and it was clear that he was badly spoiled, such a rarity in this climate that someone who by all rights should have been mocked was overtly respected and whispered about in secret.

Vivek had never come less than first in class. In India, even at the earliest of ages, everyone is ranked according to region-wide and increasingly nationwide examinations, and these records are posted for public consumption. From early on, there’s a clear sense of who might have a shot at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), the Ivy League of Indian universities, and who might end up as a night watchman at a paper factory. So imagine his surprise when the exam scores were posted at the midterm and Vivek found himself second. To the American.

I usually tried to get along with everyone, my playground skirmishes notwithstanding. I loved both the sons of chai wallahs and the daughters of memsahibs alike. I roughhoused with the twin brothers who had flunked different grades, as if having one stay behind fated the other to eventually join him. I stayed back some lunches, at Amma’s insistence, to help Mahesh subjugate irregular English verbs like “misunderstand” and “crossbreed.” Certainly I didn’t understand the culture of competition at a school in Tamil Nadu. I simply saw my name at the top of the list and was inwardly pleased and outwardly dismissive, like I had been when I won the regional spelling bee back in Virginia.

Vivek, on the other hand, was furious. I began hearing from some of the other boys that he was going to call a big-time mobster, or Dada goonda, to scare some sense into me. His parents spoke to the headmaster to allege possible cheating. How else could a foreign transplant, having joined a school year already in progress just months before, be able to perform so admirably, especially when he spoke his native tongue laboriously, knew next to no Hindi, and couldn’t read or write the Indic scripts? I didn’t know myself how I had done it and shrugged when the headmaster congratulated me for scoring so highly on my exams.

I thought that was that until one afternoon I returned from lunch to find my satchel missing. My textbooks and composition books all gone. Amma would be furious. Hot spikes of tears gathered at the ducts, and in the concerted effort to keep them there, I sprinted from the classroom. My classmates stared, but I ignored them all.

That evening, over admonishments about my scabby knees and mud-splattered uniform, I told Amma what had happened. Even though the great majority of other students were in much more desperate need, the only person I could think to suspect was Vivek. Amma listened to me, asking me when I had seen the bag last, wondering if I might have misplaced or forgotten it. I shook my head. She soothed me not to worry and that she would pray God.

That night, never one to flinch from unfairness, Amma called Vivek’s parents. The next evening she informed me that we would be having a rickshaw ride instead of dinner. We zipped by Ezhumbur, the Madras central station with a platform where cars can be driven nearly to the side of the train, and the statue of Manu Needhi Cholan tending to a cow whose calf had been killed under a chariot’s wheels. We arrived at the fashionable district of Mylapore, whose name was derived from a phrase roughly translating as “the land of the peacock scream,” and scream they did in my prepubescent mind, the hot aathas in tight-fitting salwar pants and the bangled bajaaris hooting and hooking elbows with anyone who strode by their storefront. Amma pulled me by them quickly.

We entered a concrete flat, screened in by corrugated steel, and took an elevator up to the top of a modest tower. There Amma knocked, and I stood behind her, bashful and inquisitive. A portly woman in a sari opened the door. Her hair was in a tight bun, her bulgy midriff exposed. I stepped in tentatively behind Amma. The room we were in was all-purpose. There were large bureaus against the wall, a chapati griddle, a pressure cooker, and a masala dabba emanating a trail of scent from atop an ironing board. There was a doctor’s anatomical skeleton in one corner of the room, a plastic skull wearing a Yasser Arafat keffiyeh and a garish wristwatch. There was a desk piled high with books, and there, in the center, was my spirited-away satchel.

A bespectacled, rail-thin Dr. Mithranandran looked warily at our entrance. Behind him Vivek looked like he had been crying, and behind Vivek two younger children, a boy and a girl, peered out curiously at us. Vivek took one look and turned his back on us, either in embarrassment or in anger. I didn’t want my bag any longer. But my mother smiled and warmly introduced herself to Vivek’s family.

I can still recall the compressed action of that evening. Chai and biscuits were brought out with photo albums. The doctor spoke of a novel remedy for curing piles and fistulas. There was laughter as Vivek’s siblings sprinted around the house, and eventually our mothers pushed Vivek and me together on a piano, which was under a stack of Kashmiri rugs. They wanted us to duet out our petty rivalry, and amazingly, it worked.

By the end, I had my arm around Vivek, promising him I’d help him with his English grammar if he would help me with Indian history and Tamil pronunciation. I had my bag back and harbored no hard feelings. We were two tart and sticky tamarind seeds in a pod, possible bum chums for life, although now, when I think back on that evening, it’s the magic of Amma I conjure, rather than the mending of a relationship with someone I would rarely see again.

While Vivek and I did study together a couple more times at M.A.K. Convent, that brief interlude facilitated by our mothers was ephemeral; Vivek was still spoiled and grating. Plus, I was only a visitor.

So, at the end of the term, I gave Mickey Mouse Mahesh the two sets of my uniform, complete with suspenders and bow ties, and he acted as if I had bequeathed him the crown jewels. Amma encouraged me to leave Vivek the very satchel he had nicked from me. Though he made a big show of refusing it, I insisted, and he shuffled home with it slung over his back. It’s only in retrospect that I see the slight bite in the gesture. Ever practical but often much more, my Amma.

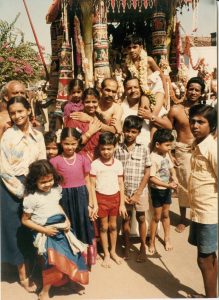

Marriage of Rajeswari Krishnan and K.H. Shankar, Ayyanna Gowder Kalyana Mandapam, Coimbatore, India, August 1970

4.

I remained in Madras for the rest of that winter and turned eight during the Tamil harvest festival of Pongal, after which I was named. Ravi means “sun” in Sanskrit, and the festival pays homage to Lord Indra, supreme ruler of the sun and the clouds that bring the rains that help produce the crops. There’s a communal ritual where useless or broken household articles are thrown into a bonfire made of wood and cow-dung cakes.

During Pongal, I attended a temple pooja, a ceremonial ritual of worship where, alongside offerings of sugarcane and bananas, fresh rice is boiled with milk in an earthenware pot tied round with a turmeric plant to be offered to Indra. Another festival day, cows walked the streets garlanded with colored beads, tinkling bells, corn sheaves, and cut flowers.

Slowly, over the course of those months, my grandparents seemed revitalized. My grandmother wore a head scarf and accompanied us to the beach one afternoon, and my grandfather was able to leave his Rajasthani chair and go for walks with my sister and me, clutching at our arms with a vicelike grip. I can still conjure the scratchy bristles of my grandfather’s cheek, and how he hid rock candies in a small jar in his bureau, which I would filch to crack my teeth on.

How different my life was in this flat of homes where there was a security guard who slept on top of his chappals in front of the complex, and where a cook and a cleaning person would come a few times a day to prepare meals and tidy up. At first, the way my grandparents, not rich themselves, employed servants embarrassed me, but over time, I got accustomed to them as members of the family, which is a lie, of course. The servants had pet names but were not allowed to sit on the furniture or use the air conditioner. When we watched TV, if the cook wanted to join us, she would squat on the floor.

There’s no such thing as personal space or privacy in an Indian home, and so the servants would generally be ignored, as if they were another one of the appliances, whirring around like a fan blade, making ambient noise like static from the transistor radio. I don’t mean this to imply that my family was cruel; I would often see my grandmother slip a hundred-rupee note into the folds of the cook’s sari, or give them leftover sweets from our dinner. I’m sure my grandparents actually saw their employment of servants as a kindness, for they provided sustenance and accommodation to those who would have otherwise been without those human necessities. However, what they didn’t see—what I learned not to see myself, until I could eventually erase my own blindness—was the structural inequality woven into the very fabric of Hindu culture.

We ended our stay that year by pilgrimaging to a few temples. Appa had my head shaved at Tirumala Venkateswara, a famous Vedic temple in Tirupati, a hill town in Andhra Pradesh. It was sometimes called the “world’s largest barbershop” for the five hundred tons of human hair collected there each week. The act of tonsure in Hinduism is for auspiciousness and rebirth, and I can recall being a new mottai, my bare, tingling scalp rubbed with sandalwood paste, my hair in clumps upon a bronze scale. I felt free and savage. How little I was able to gauge that it might not be the most ideal hairstyle for reentering a life in progress in a Northern Virginia suburb.

As we move forward in life, we trail behind us the places we have been, the possessions we have accumulated, the memories of the people by whom we’ve been touched. When we can’t fit this all in our new homes, or in our new lives, we find some repository for it all, the subconscious.

I read somewhere that the self-storage industry is one of the fastest-growing sectors of real estate in the last half century, which I guess makes sense, given the culture of American consumption. Someday we will use that snowboard again, right? Our children’s children will indubitably want the hive-shaped evidence that their grandfather once was the regional spelling bee champion?

I’m not one to judge, because I rent a storage space myself, mainly crammed with CDs and books. However, I know somewhere in there I have a box that contains some trace of the time I spent as a young boy in India—a shoebox full of 35mm film canisters and photographs of my grandparents, now deceased; of my sister and me in our M.A.K. Convent uniforms; of Amma waving at the camera from inside of a rickshaw. But try as I might, I can’t find the box anywhere.

Instead, opening yet another box full of books, I find a volume that I haven’t cracked since graduate school. It’s Homi Bhabha’s The Location of Culture. I open it up randomly and come upon a highlighted sentence: “The theoretical recognition of the split-space of enunciation may open the way to conceptualizing an international culture, based not on the exoticism of multiculturalism or the diversity of cultures, but on the inscription and articulation of culture’s hybridity. It is the in-between space that carries the burden of the meaning of culture, and by exploring this Third Space, we may elude the politics of polarity and emerge as the others of ourselves.”

In the margin of the book, I’ve jotted down something about postcolonialism, about how the dynamic of the migrant, the exiled and diasporic complicate… what? I can’t read my own handwriting from decades ago, which, in and of itself, testifies to aging, but also to the inbetweenness and ephemerality of identity, how we transform by keeping alive some part of us, yet always move beyond it, leaving ourselves behind. Deconstruction, postcolonialism, and poststructuralism had seemed so urgent back then, but now I struggle to glean Bhabha’s meaning, even as I feel the power of the Third Space more deeply in my bones.

I must have been living there when I returned to my American elementary school in the spring of 1982. My hair hadn’t grown back, and so I was greeted by my classmates with guffaws and cancer patient jokes. Slowly my hair grew in, and I started loving Sting’s band, The Police, the World Wrestling Federation, and monster trucks. My sister and I spoke sometimes about India, then less and less frequently, and my memories of our year away began to fade to small details: the scolding string of invectives from my grandmother, who considered me too loud and too little devout (she would pass away a year after our visit, and we returned to India in 1983 to perform her sacred rites and my own poonal, or sacred thread ceremony); Vivek’s lavender odor and Mahesh’s gentleness; the rawness of knuckles that have been rapped on by a ruler; the dusty wrestling with smaller boys whom I might have physically more resembled if not for my own parents’ immigration nearly a decade earlier.

The author’s poonal (sacred thread) ceremony, Vadapalani Murugan Temple, Chennai, India, May 1983.

I passed through that time in Madras, and that time passed through me, and if you could freeze that moment of my life at a cross-sectional slice, you might be able to see—what? A boy desperate to fit in? Someone who had learned all about the ease of making and discarding friends? Or someone who had learned to navigate a world that contained Viveks? Would I elude, as Bhabha had predicted, the politics of polarity to become the other of myself?

I’m not sure. I do know, though, that when I was back in America, I possessed a knowledge that the other kids in school did not, which made it a secret and convinced me of the very notion that Amma was always telling me: that I was special. The very qualities which made me unlike Tommie and Billy did not have to be a liability, but could heighten my sense of superiority, especially during those moments when the world seemed particularly harsh and judgmental. The marvelous dislocation of my year abroad grew in me a sense of difference, even as I longed to assimilate. The outsider learns to observe, and the cohesive self begins to disintegrate.

Back home in Virginia, I prayed to Hanuman devoutly and then derided myself for spending even an iota of energy on a monkey-god. Ridiculous. I spoke Tamil with Amma and Appa, and perfect American English at school. I remained a vegetarian but sometimes pretended that I ate meat. I lied about my age, wanting to be thought the same age as the kids in my class. I began to take silly risks on the school bus or on the playground, believing it made the other kids admire me more. I nurtured a shadow within myself and projected another face to the world. Sometimes, unbeknownst to me, those selves would switch.

As I grew older in America, I pushed the Indian part of myself further and further away. “Jana Gana Mana” wasn’t going to help me make the soccer team or to talk to girls. It wasn’t until much later, perhaps graduate school, that I began to understand that the anxiety of my predicament might have been a boon all along, giving me two rich cultures from which to forge an identity. That I could choose the best and leave the rest. Make up a mash-up of American self-reliance and Indian satyagraha, a mosaic of Muhammad Ali and Mahatma Gandhi, Jimi Hendrix and Parshuram, the axe-wielding avatar of Vishnu. I too could partake in the American ideal of continual reinvention and in a bastardization of Dale Carnegie, could mobilize my “exotic” heritage to win friends and influence people.

I used to think that identity was a little like Amma’s anjarai petti. You have separate compartments for cumin and mustard seeds, for turmeric, fenugreek, and red chili powder, for ground cumin or coriander, for star anise or whole dried red chilis. You have little boxes for your identity as a jock, a chess champion, a skater, and a dutiful son; you have a few dashes of Desi, and a heaping tablespoon of Yankee, and depending on who you were dining with, you could apportion out these elements in just the right proportions and flavors.

I know now that identity doesn’t quite work that way. Even when we are trying hard to project a certain self into the world, all that we have pushed away still lurks unseen, like dark matter, gaining in power. All of us inherit complicated legacies and generations of trauma, and all of us are alienated, at some point, from someone or somewhere, and very often from ourselves. In such a way, we create the others of ourselves and the tidy compartments to keep ourselves in; thus, the feeling of being in exile remains virtually universal, though knowing that does surprisingly little to make us feel any less alone.

From the forthcoming Correctional by Ravi Shankar. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.

Ravi Shankar is a Pushcart Prize-winning poet, translator, and professor. He has published fifteen books, including W.W. Norton’s Language for a New Century, Recent Works Press’ The Many Uses of Mint, and the Muse India Award-winning Tamil translations, The Autobiography of a Goddess. He has taught and performed around the world and appeared in such venues as The New York Times, NPR, the BBC, and PBS NewsHour. He received his PhD from the University of Sydney, and his memoir Correctional is forthcoming in 2021 with University of Wisconsin Press.