By SCOTT GEIGER

The Mississippi River meets only one waterfall on its wayward transcontinental course. It comes early, in the northern Midwest, at a site the Sioux knew as a place that was part real world, part spirit world. Seventeenth-century adventurers rumored about a “pigmy Niagra” called St. Anthony Falls. Pioneers from the young United States reached these waters early in the nineteenth century; they established simple mills for grist and lumber just as soon as property rights could be legally defined.The mills grew and industrialized over decades, triggering the rise of Minneapolis. A feature of nature became a technology servicing the city. The names Gold Medal Flour and Pillsbury still loom in enormous metal type on opposite sides of the historic railway bridge leading into Minneapolis that was new when F. Scott Fitzgerald was a boy. The historic mills themselves have gone, though, and today Stone Arch Bridge belongs to pedestrians, cyclists, and the students of the University of Minnesota. Looking north from the bridge they see an amphitheater of a spillway, tall gray waters pouring between a research lab and hydroelectric plant on the east side; a lock-dam barge elevator run by the Army Corps of Engineers on the west.

Two modern Minneapolises meet at St. Anthony Falls. The first is a Midwestern city of commercial real estate, of skybridges, of eight-lane intersections, and Mall of America Field. A second Minneapolis comprises the 6,725 acres of green space administered by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. In the 1880s, landscape architect Horace Cleveland designed a circuitous park to preserve and connect the region’s most beautiful natural features: its lakes, Minnehaha Falls, and the western Mississippi Riverfront. The Grand Rounds, as Cleveland deemed his park system, preserved the scale and character of American nature for the refreshment and recreation of the emerging industrial city. A century and a half later, the city’s economy is radically different, yet the parks remain intact, pristine. A third kind of Minneapolis, emerging today, will leverage the Grand Rounds and sites like St. Anthony Falls to reform the rest of the city toward a sustainable balance with the cycles and systems of nature.

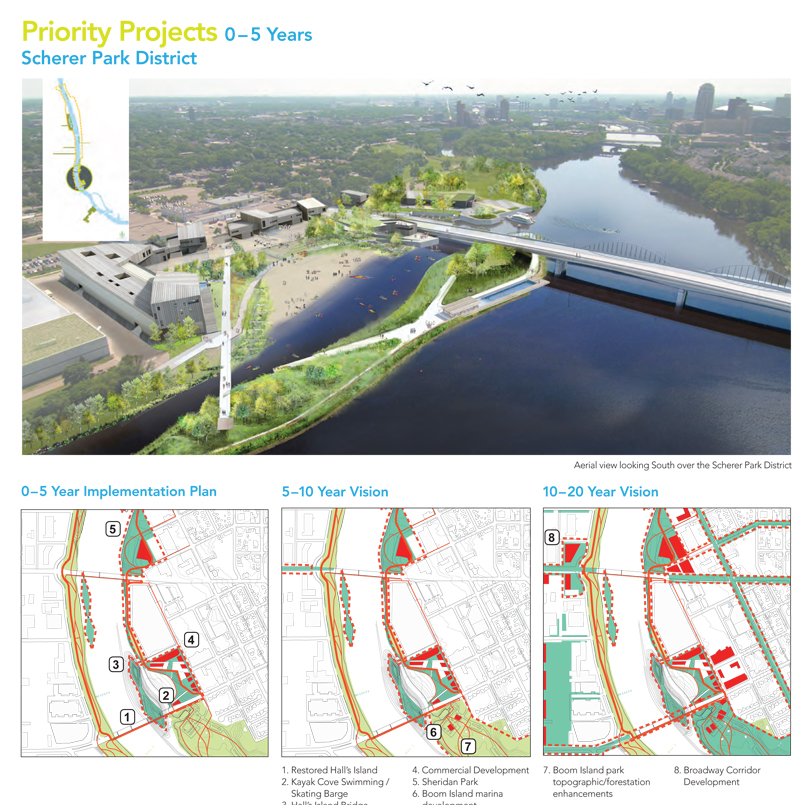

Over the past year, “Buckminster” entries for The Common have auditioned the literary potential of certain kinds of architectural documentation and design media. RiverFirst is a proposal for a new Minneapolis, represented with writings and architectural media created by Berkeley-based landscape architect Tom Leader. Yes, it proposes a series of interventions across the city, some achievable in the near term, others that might be implemented over twenty years. But unlike a city master plan, its commissioners have no political power, no money to implement the vision. RiverFirst is instead a cultural campaign to align many people and organizations around a shared tomorrow.

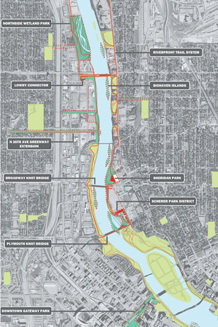

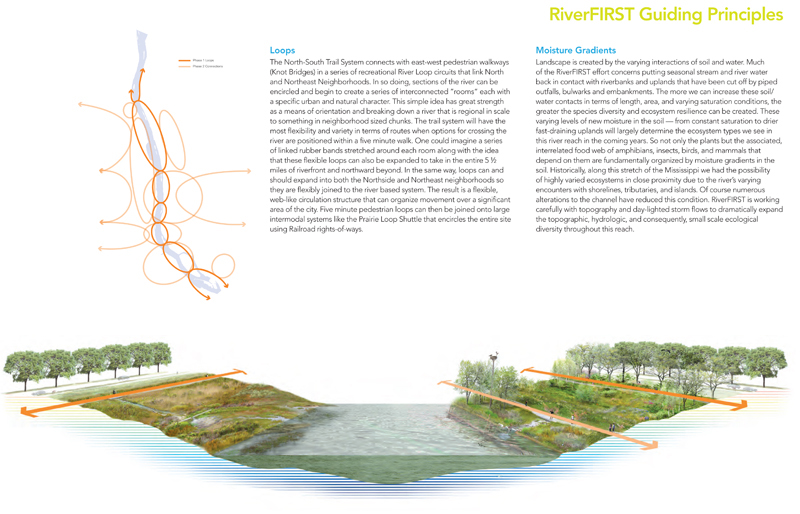

In 2010, the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board worked with a local activist named Mary deLaittre to produce a design competition for a framework vision for the future of their Mississippi riverfront. The competition’s strategic area ran north from St. Anthony Falls for five miles, and projected a future in which the historic industrial waterfronts transform into parklands. The winning entry came from Tom Leader Studio, with architects Kennedy & Violich of Boston in collaboration with fifteen other entities and organizations, from structural engineers to botanists, global real estate analysts to Minneapolis-local community groups. RiverFirst was Leader’s title for their effort, and the competition entry included a logo that the campaign has since adopted. New parks and bridges improve the patterns and means of circulation throughout Minneapolis. Renewed wildlife habitats create an ecological infrastructure for the city: city-wide stormwater filtration ends combined sewer overflow, “soft” edges along the river guard against spring floods, and new trees extend the cooling benefits of urban canopies to relieve the city from summer heat. Meanwhile, Minneapolitan quality of life re-prioritizes the Mississippi River as the city’s focus.

Since the competition, Mary deLaittre has taken up advocacy for RiverFirst through a new nonprofit agency called the Minneapolis Parks Foundation. Their agenda is not merely to illustrate possibility, but to animate the community and the government to act upon possibilities identified by Tom Leader Studio’s team. The center of this advocacy is through the RiverFirst campaign website. But the Parks Foundation also runs public education programs, events, and a lecture series in collaboration with the Walker Art Center.

RiverFirst appeals to Minneapolitans through an amalgam of fact and fiction. Architectural media enumerates its intentions: diagrams, plans, and sectional perspectives, which are three-dimensional drawings that slice up the landscape like a piece of cake to reveal topography and subsurface soils and geology. Tom Leader Studio’s team also chose to envision futures for key sites along the east and west riverfronts, depicting these new parks in aerial perspectives and imaginary scenes generated from parametric modeling software and polished in Adobe PhotoShop.

The new Minneapolis makes its debut through these rendered images of RiverFirst. Their lighting is natural, colors toned modestly. Ordinary people texture their edges, gazing into the parklands. But the proposed projects do vary by degrees of complexity, with their implementation set to take place over years. Some pieces of RiverFirst will be built in the next five years, others in the next twenty. An extension of the trail system further north is easy to visualize, but RiverFirst’s long duration schedule invites science fiction. One such spectacle is Scherer Park, a new island with a swim beach on the site of a former lumberyard. There are also new bridges exclusively for pedestrians. And a network of floating artificial islands, described as Biohavens, appears to clean the Mississippi and support wildlife habitats. We see in these schemes not only the Mississippi landscape futures, but the actions of Minneapolitans imagined in the throes of daily life.

Which other classes of culture operate at such scales? Involving so much land? And over such a duration of time?

Hollywood films and TV shows can support broadly popular and occasionally even enduring works of art. They ask nothing beyond appreciation and the price of admission though. Commercial advertising positions before audiences the products or luminous brands that bid to transform your life. We carry home an iPad or laptop, taking into ourselves a little of Apple. Then what?

The success of the Minneapolis Parks Foundation’s mission to steer the entire city toward a superior future will rely on the RiverFirst vision almost as a founding text. In this way the project resembles a social movement or a political campaign. Except that the Minneapolis of tomorrow will be brokered in mosaic, year by year, as lands are acquired and funds secured. The needs of local communities will change; new opportunities will appear, technologies surely will evolve. January brought news that the U.S. Army Corps will decommission its barge elevator, and last week saw the first public work session for a RiverFirst priority project site—St. Anthony Falls, to be designed by landscape architect Kate Orff as Water Works Park.

What is RiverFirst? Most generally, it appears to be a flexible, shared story about the city’s future, addressing government policy, real estate, ecology, wild life habitat, public space, sustainability, and daily life. The protagonists will be a generation of Minneapolitans making up real lives in the imagined landscapes of a city coming into alignment with its natural surroundings.

Scott Geiger is the Architecture Editor for The Common. His fiction has earned a Pushcart Prize and a 2012 New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship.