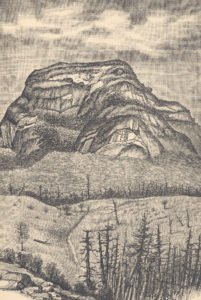

Romanes, Whiteside Mountain from Road to Grimshawes

Whiteside Mountain, North Carolina

Some call it the world’s oldest mountain. Once, millions of years ago, it was Mount Everest.

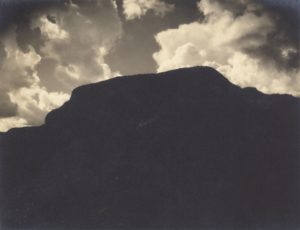

Quartz and feldspar stripe the cliffs of this vast pluton, which looks burnt, as if it had survived some great conflagration or were, in fact, a meteorite scarred by its descent through the atmosphere.

This mountain in western North Carolina, called Whiteside Mountain and Sanigilâ’gĭ in Cherokee, is a site of an ever-shifting strata of personal and historical memory. In one of my earliest childhood memories, partial and overexposed like a polaroid cutout, a king snake bakes on the brilliant white rocks of the summit. Subsequent memories on the mountain increase in clarity as they approach the present. Among countless others: hunting for quartz crystals; an icicle duel with a friend; experimentally hanging from a cliff’s edge; confessing my love to a girl as we bounced up and down, lightly, on the branches of a red oak from which we could see Georgia; a year later mourning that love’s loss; a bitter series of visual hallucinations when my mental illness peaked; satellites arcing across the night; and a peregrine falcon diving through mist.

But these personal experiences are shot through with, and colored by, the verbal and visual accumulations of history. In my mid-twenties, I discovered old black and white photographs of the mountain by a German immigrant, Reinfried Armstrong Romanes, who explored and photographed the region in the late 1930s. Ever since, I can’t visit the mountain without reflecting on Romanes’ stacks of photographs documenting those bell-shaped cliffs from every cardinal and ordinal direction; how little the mountain has changed over eighty years and yet how mysterious it remains.

Romanes, Whiteside Mountain from Bearpen Road

Whiteside taught me about yellow and black birch, witch hazel, red oak, eastern hemlock, and Fraser magnolia; about wild sarsaparilla, rhododendron, azalea, goldenrod, and gray beard-tongue. But even more, it taught me to love winter’s silence and the sunset’s red light captured in ice; to watch the stars emerge one by one, as if beckoned by the pressing of keys. To close my eyes to the cold and allow memories, the good and the bad, to flow upwards like water touched to paper.

But increasingly my own memories are combined with, and even altered and eroded by, the memories of others. The Cherokee compared Whiteside to a sheet of ice and told of a bridge once anchored to the summit spanning a hundred miles (ending near the Hiwassee River in Tennessee) that was destroyed by lightning. In the nineteenth century, Rebecca Harding Davis dropped a pebble from the mountaintop and watched it fall straight to the valley bottom without striking a single rock. Charles Lanman told of a black bear that emerged from a cave, was startled by a man, and slipped off a ledge, falling a thousand feet to its death. In 1859, Henry Colton recounted the story of a sadistic man “who tied two umbrellas to his dog and dropped him off this precipice…the dog land[ing] safe and sound at the bottom” (naturally, the canine aeronaut avoided his owner for the rest of his life). Soon after the Civil War, northern journalists and prospectors speculated that a “second California” of gold and silver lay within the mountain. Another source reported that a devil-worshipping sorcerer resided in one of Whiteside’s caves, and later raised a question about so-called Indian ladders—tree branches cut to form steps—being used to scale its high cliffs.

Zeigler and Grosscup, Unaka Kanoos

In mid-October, about a half-hour before sunset at the overlook on U.S. Route 64, Whiteside casts a small shadow that grows, very gradually, into the precise shape of a black bear on the valley floor. This is a rare, singular phenomenon, and makes me think of the many visions—the painful and the beautiful—the mountain has afforded me. In my late teens and early twenties, I was extremely sick. I’d force myself to climb the mountain, even though I’d grown strangely afraid of it. I didn’t want to be owned by my fear. On one occasion, the rhododendron leaves, flickering like jewels, morphed into a panther running at me full-tilt. On another, a door opened in a cumulus cloud and I crouched on the summit marker in sheer panic, my arms shielding my head.

Romanes, Whiteside Mountain

Fortunately, I’m no longer crushed in that vise. When I visit Whiteside, the me and the not-me, the private and the communal, swirl together like marbling ink. I see sepia photographs, a former lover’s eyes and teeth, a waterfall of stone, a giant’s charred scalp, a flying dog, the ruins of a bridge, a lonely sorcerer, and gold and silver veins in the mountain’s core, miles deep, too far for drills to plumb. This, I think, is Everest’s future. This is my lodestone. This is a geology of memory.

Gregory Ariail lives and teaches in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Indiana Review, CutBank, The Offing, and others. In 2019 he thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail.

All images are from the R.A. Romanes Collection and Special Collections Books of Hunter Library, Western Carolina University, which has generously granted permission to use them.