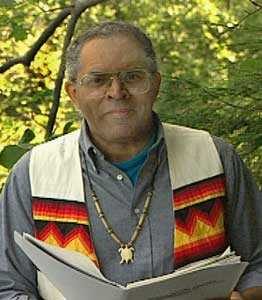

S. TREMAINE NELSON interviews RON WELBURN

Ron Welburn is a Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he teaches American Literature, Native American Literature, and American Studies. His ancestors include Gingaskin and Assateague from the Delmarva Peninsula, Cherokee, Lenape, and African American. Professor Welburn received a B.A. in both Psychology and English from Lincoln University, an M.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Arizona, and a Ph.D. in American Studies from New York University.His research and teaching interests include ethnohistory of eastern Native America, cultural studies, and jazz studies. S. Tremaine Nelson spoke with Ron over the phone about poetry, New York City, and two authors whom they both very much admire, Ralph Ellison and Leslie Marmon Silko. Ron’s poems “Seeing in the Dark” and “When You Know a Hard Sky” appear in Issue 06 of The Common.

*

S. Tremaine Nelson (SN): Where were you born and raised?

Professor Ron Welburn (RW): I’m a native of Berwyn, Pennsylvania, in the northeastern part of Chester County, on Philadelphia’s Main Line. Quite rural when I was a kid.

SN: Did you go to high school in Pennsylvania?

RW: Yes, up through college I went to school in Pennsylvania. I was in first grade when we moved into Philadelphia, so I did most of my schooling there–but having relatives out in Berwyn and other parts of Chester County I was always out there, too. I felt like I grew up in both places. I finished high school in Philadelphia and worked for about a year in data processing and then went onto Lincoln University, where I graduated with a double major in Psychology and English.

SN: Me too! I had the same double major. There aren’t very many of us.

RW: No, there aren’t. My interest in psychology at the time had to do largely with optics, perception. I had courses in physiology and abnormal psychology, too.

SN: When did you decide that literature was your greater intellectual passion?

RW: Well, along the way with psychology, there were a few fellow students and we had a literary magazine and I started getting the bug for literature. Summer after my junior year I started writing short stories. I was taking literature classes along with the psychology. I was writing poetry and publishing in our school newspaper The Lincolnian. We had a coterie of students interested in poems, a very nurturing environment.

SN: Did you study psychology to better understand how people think? Did it inform your writing?

RW: Yes, that’s how it turned out. I went into the Nine-to-Five world in a bank, did a lot of data processing. I had started reading the “dangerous” literature by people like Robert Reisman, The Lonely Crowd, William H. Whyte, The Organization Man. I had always read history. I didn’t read that much literature growing up. I think that I wanted to figure out what people think, to understand their motivations, their actions. I was trying to look at it dispassionately because I couldn’t figure out some things people saw in society and why people persisted in acting the way they did. I found that reading literature, short stories and novels, was open access to the mind, even on the level of fiction and metaphor, it deepened my understanding of human behavior and psychology.

SN: Could you talk about American Studies and how it relates to English Literature?

RW: Early on, I could appreciate the correspondences between literature and the arts, music in particular, and painting, dance, and certainly the place of a literary work in a historical time and context. That’s where the foundation for American Studies came about. When I went to NYU in 1975 to start my doctorate in American Studies, the history people didn’t do culture, they told me. Go to the arts. But I had a very good historian named David Reimers who was interested in immigration and social history, which linked me to oral history. While I was finishing my doctorate I worked at The Institute of Jazz Studies at the Rutgers Campus in Newark. I became the Coordinator of the Jazz Oral History Project. Having always been interested in my family’s stories and history, it was a natural fit for me.

SN: So how does a written literary tradition coexist with an oral tradition?

RW: In Native culture, indigenous cultures, are oratures with handed-down stories, creation stories, stories that explain how things are or reflect a belief system of a culture or a family. I think certainly in my experience I always enjoyed how my family members, my uncles and aunts, had this way of making certain anecdotes come to life about strange things that happened out in Chester Country. They spoke with a sound, a lilt, which I absorbed into my own writing. The old spoken stories gave me a strong appreciation for the written word. Among the first writers I enjoyed reading were Mark Twain, William Faulkner, Jean Toomer, Ralph Ellison.

SN: Invisible Man. Absolutely. I re-read it every year. It covers every major intellectual topic.

RW: Right. When it comes to Native authors, I really had to dig around until House Made of Dawn came along and won the Pulitzer Prize. That was the first time I had the opportunity to read a Native author.

SN: What was your reaction to reading House Made of Dawn?

RW: It just glowed, the language so poetic, the resonances, the analogies. Certain aspects of my own experience I felt so immediately. From other things that had happened to me on a personal level, reading it, and seeing things going on in the natural world, it’s the book that—I find myself stammering about it.

SN: It’s a devastating book. I had to stay up late at night to finish. It was so mesmerizing.

RW: You use the term devastating, but I would say it “gleamed” for me. I absorbed it on an interior level. I next read James Welch’s Winter in the Blood and Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony. Momaday started a renaissance. You had James Welch, Maurice Kenny, and other Native authors who started to find an audience. My experience as an East Coast urban Indian is not quite the same as theirs.

SN: That’s an interesting distinction to make because House Made of Dawnand Ceremonytake place in the American Southwest.

RW: Right.

SN: Is there a body of literature that speaks to the “Urban Indian Experience?”

RW: There are a number of people who have lived in certain cities like Richmond or Washington. I think more writing by Native authors from the East Coast will eventually emerge. There is a fine poet in Virginia named Karenne Wood whose collection is called Markings on Earth. She’s Monacan. She’s one of the best voices I know of coming out of the greater southeast. In the northeast, Joe Bruchac is Abenaki, also a good writer. There are Haudenasaunee writers, especially Mohawk and Seneca.

SN: What is your experience reading Louise Erdrich?

RW: Love Medicine and The Beat Queen were really quite good.

SN: Going back to Leslie Marmon Silko, I have a copy of Almanac of the Deadsitting on my bookshelf, staring intimidatingly.

RW: It’s going to do that, yes. And when you get in, it’s going to draw you in all the way.

SN: Can you talk about Almanac’s place in 20th Century American literature?

RW: I remember getting ahold of it back in 1991. It was this huge book and took me a couple years until I read it. I wanted to teach it and have done so twice. It’s enormous. The historical, political, cultural scope of the novel is immense. It’s tied to the image of a serpent from the Pueblo people and Aztec people in southwest Mexico. The novel is also an indictment of any industry that ruins the earth, that eats up the earth’s atmosphere, an indictment of people who care only for money at the expense of the earth. It’s really a hemispheric novel.

SN: How have your students reacted to it?

RW: Some of the students reported being overwhelmed by it, while others enjoyed it. I think a lot of Native Literature and so-called Ethnic American literature is challenging if the students have not yet read outside the American Canon.

SN: The high school canon.

RW: Right.

SN: Earlier, you mentioned NYU. What was it like living in New York City during the 1970s?

RW: I had occasionally visited New York, but living there was a lot different. I’d had a summer clerical job there right after high school, and lived in Brooklyn. I went to Birdland, the jazz club, all the record stores, some of the museums. And on my subsequent visits through the 1960s I began to see certain aspects of New York that were angrier, more intense. Later, one of the classes I took at NYU was called Fiction and Democracy, and it was taught by Ralph Ellison. He was erudite in a homespun fashion. His perceptions of the confluences of culture were fascinating. I was quite in tune with what he was seeing and understood. He had us read Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson, two books by his buddy Kenneth Burke, and a book by John A. Kouwenhoven called The Arts in Modern American Civilization. It was just a great experience.

SN: That was in the American Studies Ph.D. program?

RW: Yes. He held the Schweitzer Chair in American Civilization at the time. There were history students and literature students in a class of about maybe 45. The history students were confused by reading the literature, but the literature students got the history.

SN: Was his reputation different than it is today?

RW: I think it depends. There was a film on Ellison made in 1966, where it was mentioned that Invisible Man was voted the novel most read by a large group of American novelists. If nothing else, that put him in a literary canon as far as other writers were concerned. Invisible Man was such a novel, even by 1965 or 1970; you could not ignore the novel. But Ellison was more than just a novelist. He was a cultural commentator, a sociocultural critic. There were a number of comments and positions he took that were not popular with African American students. They didn’t understand why he liked Huck Finn, or why he liked lawn jockeys. You used to see them around, those two-feet high plaster of Paris statues of horse racing jockeys with faces and hands painted black. You don’t see them around anymore. But those jockeys commemorated a famous black 19th-century jockey named Isaac Murphy who won two or three Kentucky Derbys. A major Derby jockey. Ellison knew that and he defended it. A lot of young African Americans didn’t like that. They called him Uncle Tom.

SN: Was he widely controversial?

RW: In a way, he was. This was in the spring of 1976 or 1977. I was really happy to be in that class. I knew where he was coming from.

SN: In Issue No. 06 of The Common, we feature two poems of yours: “Seeing in the Dark” and “When you Know a Hard Sky.” What can you tell us about these poems?

RW: “Seeing in the Dark” is dedicated to a friend named Francis Martin who used to work in Food Services here at the university. We’d been friends awhile, and I was wearing my turtle amulet, a necklace, and he asked me about my background. He described his background to me as Nauset, and Nipmuc. This is Nipmuc territory, the westernmost region of it, down to Natick and northeastern Connecticut. The Nauset live on part of Cape Cod. We got to talking one day, about four years ago, and about being able to see in the dark. This is something my dad used to do: he would go into a room and my mom would say, “Turn on a light,” but my dad could say, “I can see what I’m doing.” In my mind, I decided that being able to find something in the dark without light would be very helpful. So after all those years I wrote that poem and dedicated it to Francis. Whether you’re in a forest, or a dark room, if you can just wait a minute to adjust, you can find what you’re looking for: there’s a talent in that. I wove into the poem this idea that one of the first things the pilgrims did when they came here was they cut down a lot of the trees. We think it wasn’t just because they needed the wood, but the trees were threatening to them, these dark forests, and they wanted to eradicate this stuff. An origin of American Gothic if you twist it into a fear of Indians.

SN: It adds an element to terror to the poem, the way you’re describing it.

RW: Francis was underscoring the fact that there’s no need to be afraid of what you can’t see. If your eyes and your senses are trained, you can avoid twigs and branches that come across your face.

SN: Let’s talk about “When You Know a Hard Sky,” dedicated to Don Cheney.

RW: Don Cheney was in the English Department here [at the University of Massachusetts Amherst]. One afternoon as a storm was brewing we found ourselves heading in different directions on a stairwell landing at the end of a corridor. I called his attention to how the sky looked like hard aluminum, a texture like the cover over popcorn.

SN: I can visualize it perfectly. Dented all over.

RW: There you go. It was kind of a moment where we were both looking at this, thinking not only about the level of its reality, but making analogous associations about what we do, or where we’d been. We were talking together, interpreting it together as we saw it, a natural moment not easy to forget. I think a lot of people don’t pay much attention to the sky, to the trees. We tend to take these things for granted. Even with the weeds that come up in the pavement, there’s a lot of chamomile that comes up, too. The storm was startling, wondrous.

SN: The poem reads as a sublimation of the natural into the consciousness.

RW: You have it right there. When you’re writing a poem, you don’t deconstruct your own poems. You have to write what the spirit guides you to write.

SN: Any advice for young poets, or those just starting out?

RW: Write every day, if possible. Write something. Sometimes you take a sheet of paper and nothing comes out. Read good literature. Don’t imitate. Young poets will emulate, but you have to move to the place where you find your own voice. Try not to make the poems so personal they become confessional. That has been done. Write about things that are going on in the world, look at the world around you. One can balance the political subject with the artistic craft. Not everyone has the same definition of what artistic craft is, or what it should be and do. Some political poems are lyrical, others sound off. You have to find your own way in this. You have to find your own voice.

SN: Any advice on how to balance the desire to write with the requirements of modern life, especially full-time work?

RW: You have to make up your mind. You find yourself taking a schizophrenic approach, because you have to carve out time and space every day to write. There are times when I write more in spurts. If you’re a writer, you have to write, otherwise you lose an edge; you lose your ability to see things.

Ron Welburn‘s poems “Seeing in the Dark” and “When You Know a Hard Sky” are published in Issue No. 06 of The Common.

S. Tremaine Nelson is a graduate of Vanderbilt University and founder of The Literary Man book blog.

Photography Credit: Scenic landscape, Chester County, Pennsylvannia, by John Greim.