Curated by SAM SPRATFORD and KEI LIM

This month’s recommendations depart to new and old worlds, and explore what we can bring back from them. With CHRISTOPHER AYALA’s recommendation we find ourselves among magic and aliens alike, with CHRISTY TENDING’s we return to Mussolini-era Italy, and with MARIAH RIGG’s we are brought to a climate-ravaged future. Read on to traverse these collections of stories and essays.

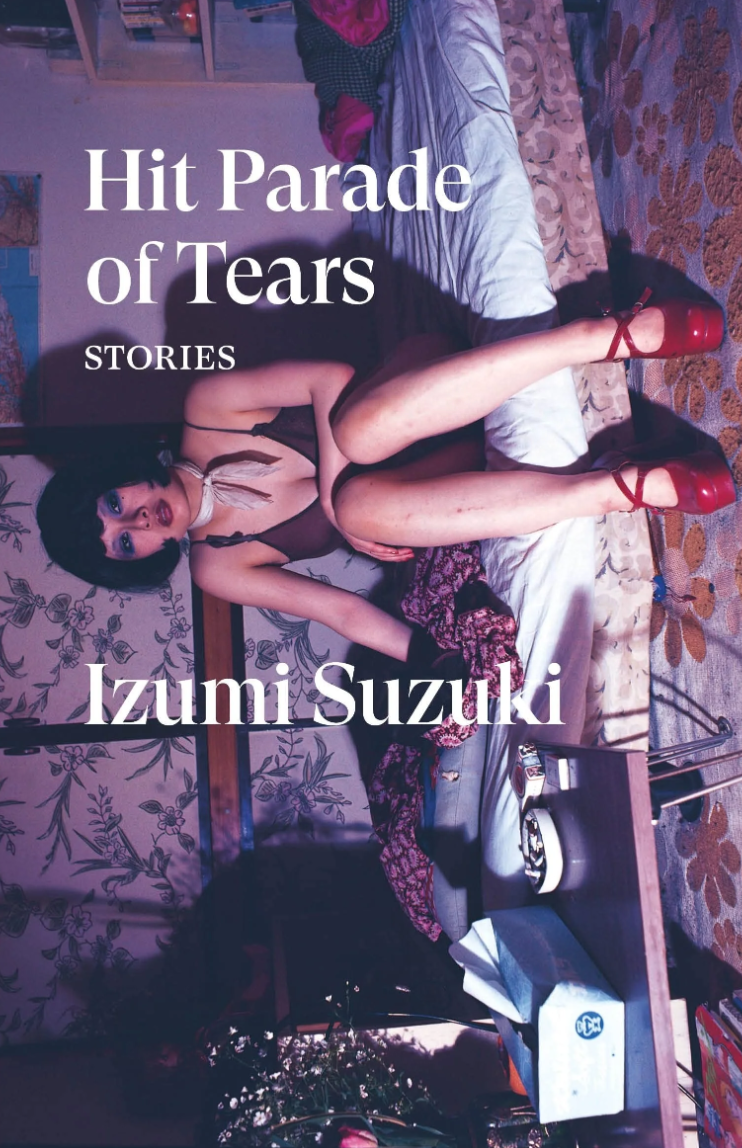

Izumi Suzuki’s Hit Parade of Tears; recommended by TC Online Contributor Christopher Ayala

I’ve taken up the habit of hitting independent bookshops wherever I travel and buying the first interesting book I see, eschewing the never-judge-a-book-by-its-cover adage and one-hundred percent judging a book by its cover. Good design suggests to me a deeper, more thoughtful curation on behalf of the press, that a book itself is an art object whose cover is a deep and personal aesthetic representing the work of the writer and the work of the press. This is exactly how I found myself in Tucson Arizona’s Antigone Books, where I was led into Verso Books’ edition of Hit Parade of Tears by Izumi Suzuki, translated by Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph, and Helen O’Horan.

The cover, a purply-magenta, sideways picture of Izumi Suzuki kind of glam and sitting on a bed, showcases the tonal register of these stories, all of them a vibe-centered, campy exploration of youth and gender amid an urban-set, sci-fi/fantasy where there are aliens, multiple timelines and, as in my favorite story of the collection, “Trial Witch,” cheating partners that, in the midst of their adultery, can be transformed into whatever the new magic user wants them to be. “Trial Witch,” “It’s a Love Psychedelic,” and the eponymous “Hit Parade of Tears”—the best three stories, in my opinion—keep centered the absurdity of one’s place in culture and the changes experienced therein. It’s a neat collection in full possession of a psychic undercurrent not dissimilar to cinema like Bruce Kessler’s Simon, King of the Witches and Anna Biller’s more recent The Love Witch. I’ve been into this kind of shit all summer.

The short of it is to say that this collection made me think about how hilarious it is that, once the type of guy who got his music only from standing around basement shows in Boston and Worcester, MA, I’ve now become a thirty-six-year-old man who goes to work and has nothing else to do but spend the money I make there on clothes. Can’t ask for a much more visceral response. So, hang me out to dry, Baby. Turn me into jerky already.

As someone with twenty plus years of direct-action organizing experience, I’m often asked to speak to this current moment, and how I think we should fight back against what is happening in our country. What I often say is that, for better or worse, we have blueprints given to us by activist ancestors who have lived through these eras before and understand the strategy necessary to meet the moment. Reading histories of resistance against totalitarianism, fascism, and military dictatorships can help us to situate ourselves in a larger context.

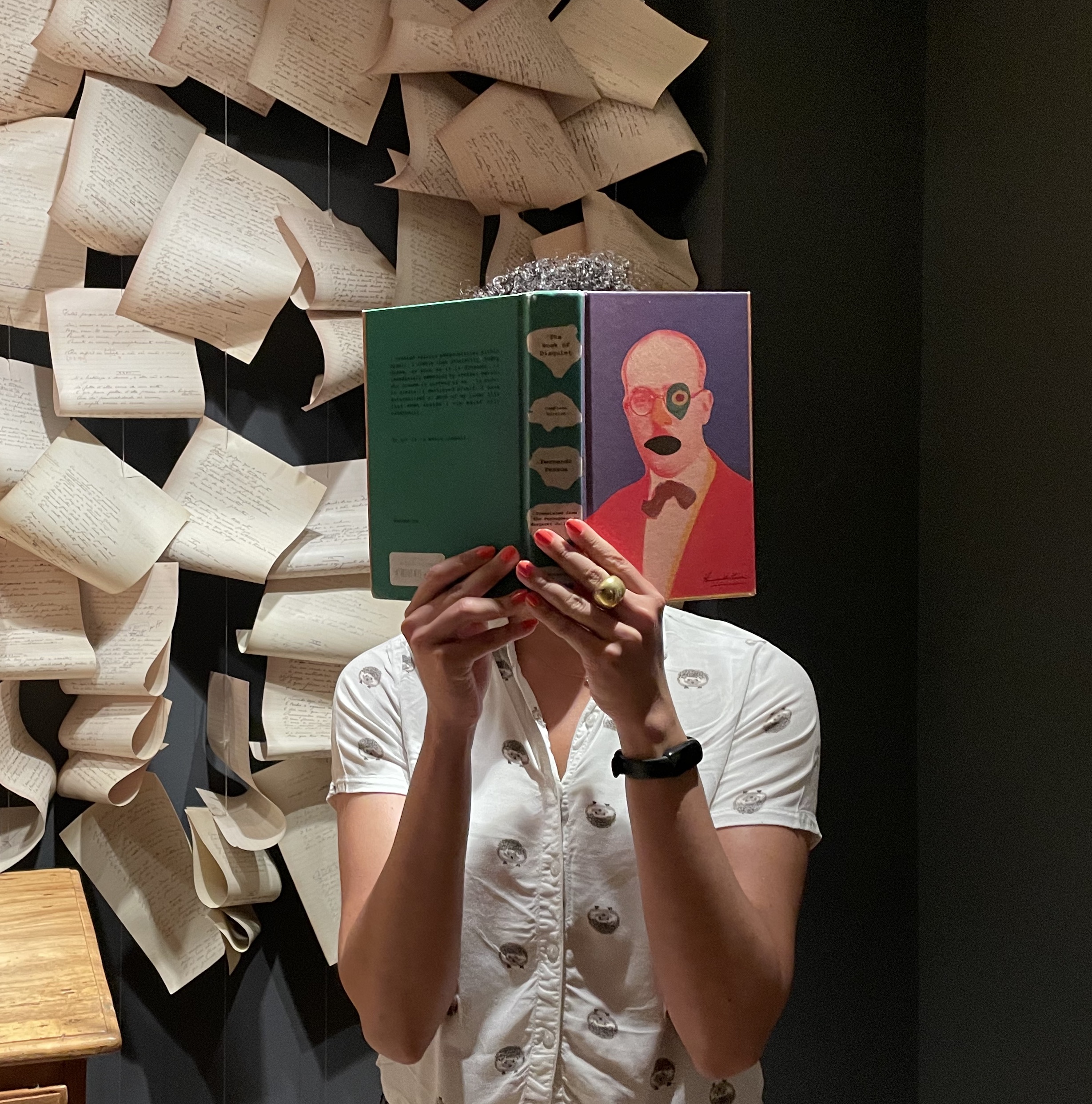

Umberto Eco’s slim volume, How to Spot a Fascist (I love a slim volume!) is a worthy addition to this canon. Most widely known as a novelist, Eco grew up under Italian fascism during the Mussolini regime and is a thoughtful narrator of how we can discern fascism from other types of totalitarianism, as well as how to properly name fascism when it arrives. His very first essay, “Ur-Fascism,” burned itself into my memory for its point-by-point accounting of our moment. In it, Eco describes Mussolini as an impossible cluster of contradictions that were more about political expediency, manipulation, and effective bluster than an actual vision for the country. He was not, Eco points out, a great thinker; his modus operandi were bombast, hypocrisy, and self-aggrandizement in service of a consolidation of power.

Eco goes on to catalog more qualities that are present across various permutations of fascism. Not all must be present, but “all you need is one of them to be present and a Fascist nebula will begin to coagulate.” In fact, the fascists don’t even necessarily agree with one another. There just has to be enough commonality, sometimes only by transitive property, that they can stomach aligning with one another in service of a similar-enough vision: the consolidation of state power through violent assimilation. According to Eco, the cultural and political symptoms around which fascism coalesces include, but are not limited to, painting dissent as treason, exploiting fear of difference, and stoking an obsession with conspiracy theories. At this point, gentle reader, I threw the book across the room for its witchcraft-adjacent prescience and poured myself another coffee.

Before he concludes the world’s most depressing laundry list, Eco gets in one final burn on the quality of fascist thinking: “Nazi and Fascist scholastic texts were based on poor vocabulary and elementary syntax, the aim being to limit the instruments available to complex and critical reasoning.” And the counter to that—a practice of intellectualism, art, and voracious reading—is one of the ways that we resist.

Eco admits that resistance is not instant. It is a long arc, but this is work that belongs to us. “Freedom and liberation are never-ending tasks. Let this be our motto: “Do not forget.”

Leyna Krow’s Sinkhole and Inexplicable Voids; recommended by Issue 29 Contributor Mariah Rigg

I currently have a concussion, and reading things, surprisingly, is one of the few things I can manage—so I’ve been doing my best to get through the stacks around my house. Last Friday, I finished Leyna Krow’s Sinkhole and Inexplicable Voids, a genre-defying collection that largely features characters from the Pacific Northwest (and one besotted octopus!).

I tell most people that I’m of the mind that the individual short story is the most perfect of the literary forms (this probably stems from my own self-importance, as short stories are the only thing I’ve successfully completed), while simultaneously being terrified that everyone who looks down their nose at the short story collection is right in thinking that the genre is a catchall for previously published work. Reading Krow’s Sinkhole proved this fear wrong—her work is a testament to the individual short story, and what a short story collection as a whole is capable of.

From the opening story, where a mother narrates the sudden appearance of a child identical to her own son, to a town infested by toxic butterflies, to a couple plotting murder in an attempt to revitalize their marriage, to time traveling philosophers and psychologists and social workers who journey to stop an infection that will lead to the end of humanity, these stories are full of awe, and horror. Characters reappear from previous stories, as in “Nicholas the Bunny,” which follows the identical child of the collection’s opener as he attempts to repopulate the forests of California by summoning grass and trees and bunnies from thin air while serving as a forest firefighter.

As someone who often writes environmentally-focused fiction, I’m always looking for work that recognizes the hopelessness I feel concerning the future of the Earth while also focusing on how (and why) the hell we keep going as our world barrels toward collapse. Krow’s stories don’t sugarcoat, while still managing to be playful. Her characters refuse to lie down in the face of late-stage capitalism’s rapid entropy, continuing to work and hope for a better world. Even when this means death—as it does in the novella, “Outburst,” where a geologist dies in a lahar born from Mount Rainier Park’s Emmons Glacier—there is still a sense of wonder and beauty. There is a resoluteness, for, as Emmons Glacier collapses, destroying much of Washington state, Dr. Andrea Carling does not run. Instead, “She stood up straight, pressing the camera to the window. She let the glacier speak for itself.” She hands the mic over to nature, reinforcing a theme throughout the collection, in which Krow and her characters let nature have the last word.