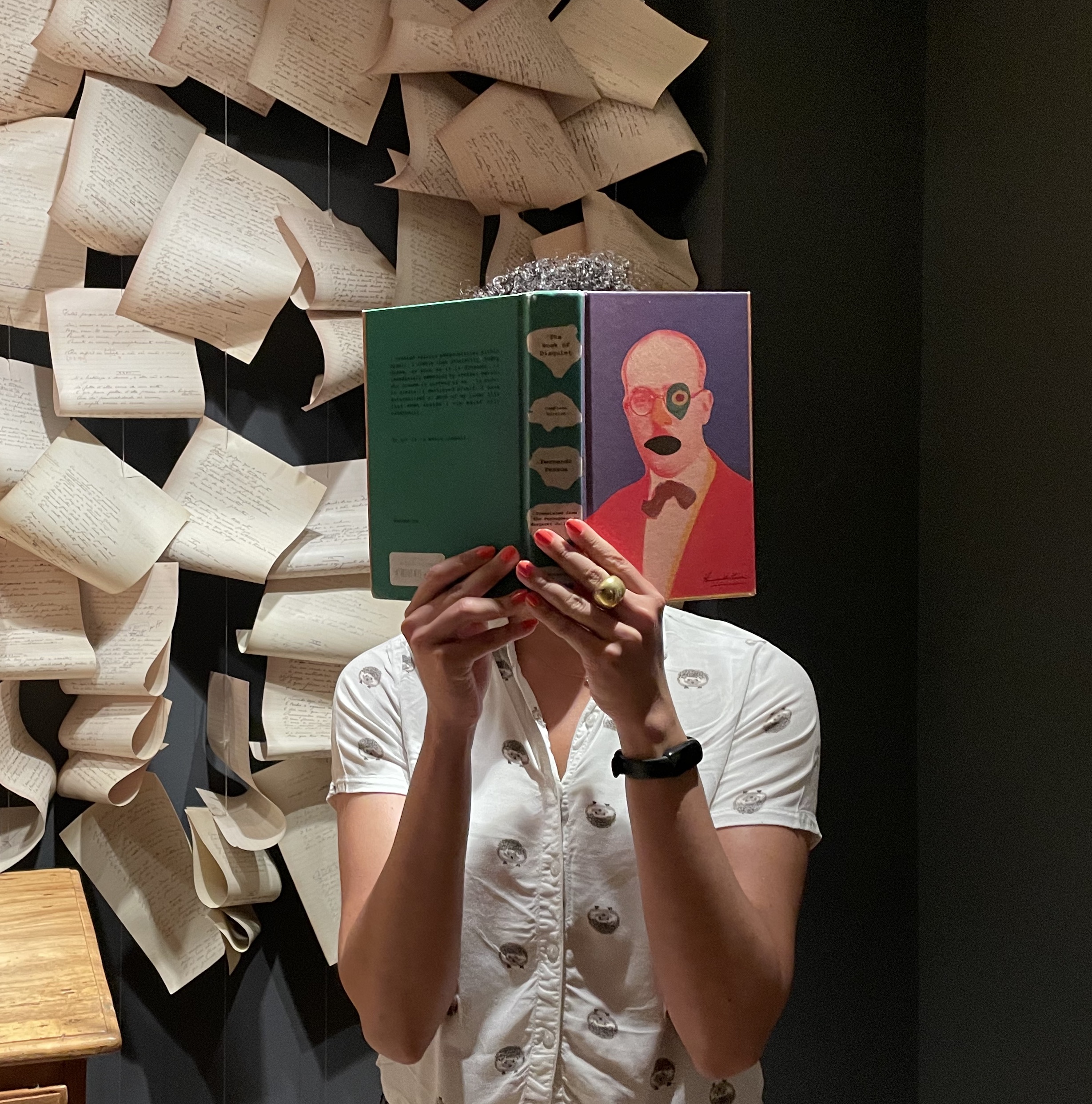

Photo courtesy of the author.

Shrewsbury, MA.

There’s a family seated at a window booth across the aisle from us; the youngest daughter keeps attempting to pronounce “syrup.” I wonder what she’ll remember of this breakfast in five years’ time. Maybe today she reminds you of me.

My earliest memories of an IHOP are sticky: the yellow walls seeping into the faux-leather booth seats; a stain on the carpet. All this beneath a crumpled-looking roof in a parking lot below the I-90 on the outskirts of Boston. Still, I could order as many blueberry-chocolate chip pancakes topped with creamy-fruity smiley faces as I wanted. The point wasn’t that I particularly liked eating the smiley faces, but that there simply were and could be smiley faces. And, in the meantime, before my hot cocoa (also with whipped cream) arrived, a crate of Smucker’s jam packets to stack and suck on awaited on the tabletop. This Ur-IHOP was sweeter than home, overtly abundant, happy, and these qualifiers felt, at the time, somehow synonymous. At home, mornings typically consisted of milky buckwheat porridge and cheese curds. Here, breakfast came with a set of primary-colored crayons.

You were a doctor with a pager then. You commuted an hour to night shifts and came home after bedtime. I used to play with your retractable ID clip, reeling it out and letting it fly back. Sometimes, you brought home miniature plastic fish from work. I never understood why or where they came from, but I pocketed them anyway.

I was finishing third grade when you and Mom traded our one-story condo for a roomier house near Worcester, closer to the hospital. I entered public school, Mom started teaching, and you got promoted. Breakfast got simple—last night’s pasta, cornflakes with a splash of milk, and, on special occasions, oatmeal. By the time I entered middle school, we were taking our meals separately, throughout the day and across the house. This is the period in my life I associate most closely with IHOP: the foggy carsickness of pubescence, the sullen silences and bitter fights. I don’t remember when, exactly, our tradition began, but it must have started on a Saturday morning, dishes piled high in the sink, countertop strewn with graded worksheets. When you suggested a trip to the diner, no one objected. Most Saturdays, we embarked spontaneously, almost conspiratorially, in the bleary, quiet hours before Mom woke up. We didn’t always choose IHOP, though, and to-go containers from every breakfast joint in the area soon colonized the fridge. Still, the anonymous IHOP near the White City Shopping Center became our default destination.

We’d drive there in silence; brown snow beside the curb, the crappy Accord wheezing heat into the cabin. When it’s cold, any small place is a comfort. Once inside, we’d both order hot chocolate, though it was never much good. I don’t remember what we talked about then—school, probably. Who I liked or didn’t like. I’d shove the scrambled eggs around my plate. You’re like me: easily spooked, boyish, with an awkward smile. We did our best to tell each other something of our feelings.

“What’s new?”

“Oh, nothing much.”

That was before the virus, before you totaled the car in Yonkers, before your mom died. That was the first time I saw you cry. We stopped going out to breakfast as often somewhere along the way; I was burning out at school while you were burning out at work. At least your snub-nosed little pickup has heated seats now.

When I first mentioned writing a piece on IHOP, you asked me if I could focus on the “International” in the eponymous “House of Pancakes.” I’d never paused much to think about that. Still, there on the menu was a stack of “Mexican Tres Leches” ($13.29, 710 cal), a token of the chain’s cosmopolitan angle on breakfast. For your generation—those who’d watched McDonalds come to Moscow—“international” still retained its aura of liberal optimism. Then there’s IHOP, with its cheery rounded lettering, a value-neutral liminal space where “international” means delocalized, culturally nonspecific breakfast fare—airplane food. Maybe you and I feel closer in transit, joined by the familiar patterns of dislocation and novelty.

I could never help you in the garden. You never had a plan, only the urge to dig. You always came back drenched; the digging was the point. It was like this at the YMCA too—you’d wander around the arm machines, a pair of AirPods in, listening to audiobooks while doing random sets of curls and crunches and presses in slippers or dress shoes. It frustrated me, probably because I’m that way too, what with the unread books and dirty dishes. So IHOP made sense for us both. Like all quintessentially American fast food chains, it’s instrumental, noncommital, infinitely replicable. In other words—simple, safe, unmournable by design.

It’s summer, the Worcester IHOP still sitting where we last left it, before the pandemic, in a plaza beside the highway. How long has it been? We’ve both lost hair—you’ve balded and I’ve buzzed. You left your Worcester job last year and are now commuting in the opposite direction—over an hour east toward Boston. Shutting the car door, you told me you’d found a new way of storing apples, meaning letting them roast in the backseat. The car would bake them, you said, just like a campfire; you love building fires, too. Toward the tall blue A-frame, churchlike and gabled. Sunday morning, and the place ought to be packed. Today, though, there’s only one family ahead of us, waiting to be seated. The rest were out swimming, presumably, in observance of the heatwave. I watched the kid squirming along the padded bench in the vestibule and remembered having sat there, too.

The place still smells the same, greasy with a hint of disinfectant. It’s all a bit smaller than I remember. We’re seated at a skinny, exposed booth at the center of the nave across from another dad and his kids. One of his girls is making a pouring gesture over her plate: syrup. The waitress hands us our menus with a look of vague disinterest—two glossy grids of dishes floating in sans-serif typeface. Meal combos. Omelet options. Calorie counts. The laminated sheet buckles in my hand. A sudden draft makes me shiver. You’ve asked for water, no ice, and I’ve done the same, almost reflexively. Out loud, you remember having ordered something very sweet and very creamy last time we were here. Tres leches, I suggest. Yes, that’s right, you say. I ask for the healthy option—protein pancakes, two “impossible sausage” patties, a portion of egg whites, and a bowl of fruit. It’s not terrible, actually. You’re flipping your tres leches around the plate with bare hands, sort of juggling them to get an even coating of the caramel. They skimped out on the syrup, you tell me in Russian. But even with their thin coating of caramel, the pancakes are cloyingly rich.

“Too sweet,” I say, spearing myself another piece.

“Just right,” you grin, sheepishly. You lost a false tooth recently, and I keep noticing the little gap in your smile.

Luchik Belau-Lorberg is a sophomore at Amherst College and an editorial assistant for The Common.