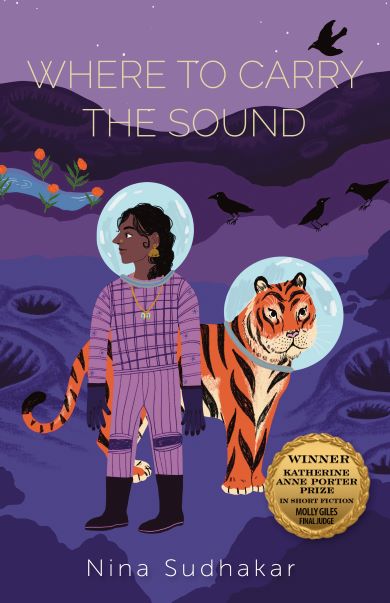

This piece is excerpted from the short story collection Where to Carry the Sound by Nina Sudhakar, a guest at Amherst College’s eleventh annual literary festival. Register and see the full list of LitFest 2026 events here.

THE BLUFF

You live on a bluff just before the edge of the world, facing the sea. Where there would be dragons, according to ancient illustrated maps, though you have never spotted such a creature. Once, when you were 9, you were shivering before the drop after a spent storm, watching the heaving water subside into its usual rhythms. The clouds clustered around the sun like moths trying to suffocate a flame. Yet one weak beam eventually slipped through, illuminating a swirl of eddies. Beneath which: shimmering, undulating scales. Did you glimpse: (I) one mythic being or (II) dozens of ordinary ones, moving collectively? You tell yourself the latter. But for a moment it had seemed possible to fool yourself—to inhabit, however briefly, another world that had been layered onto yours.

The house you live in is too close to the sea. Horizontally, not vertically; it is precipitously perched like an aerie, nestled in the gray sky. You feel vertigo sometimes looking through the back wall of windows. The panes are thick, reinforced glass but still seem fragile when compared to the elements or the black crags of rock below. You have felt on the verge for years.

Whoever built this house had hubris; whoever built it must have scorned humans as much as it seems your mother does, because the nearest neighbor is a mile away. The closest town is ten miles farther, infrequently visited for stock-up trips in an old Peugeot hatchback that otherwise rusts in the driveway. This seems to suit your mother perfectly. She has been retreating so slowly you’d barely noticed, a butterfly cocooning to metamorphose back to a caterpillar. The cocoon is the house. The cocoon is each room within it, filled with hundreds of books from which she schooled you herself. Your schooling is now done; she has taught you what she wished. You do not think the cocoon has room for you. She thinks you are ready to fly.

Entire days can now pass with no words exchanged between you, the two of you alive and alone at the edge of the world. Each of you in your worlds. The worlds drawn around you tight. Your mother spends her days with other voices in her head, one-sided conversations that do not demand any response from her. She works as a transcriptionist, faithfully documenting dictations sent to her from authors, lawyers, and corporate executives. The hallways echo with the clickety- clack of her typing. When she gets caught up in a task and forgets to eat, you bring her a plate of fruit, a bowl of soup, a toasted sandwich. Thank you, she mouths, gratitude apparent on her face, but she doesn’t remove her headphones.

So yes, you crave the company of others. For sounds beyond the drafts whistling and howling through the house, its foundations audibly sinking and creaking beneath you. For a house made of something other than wind, which carries nothing you can hold.

You have lived here as long as you can remember, which is not to say your whole life. No one remembers their whole life. It seems unjust that early childhood, ostensibly one’s happiest years, is largely unrememberable. What has your mother told you about your life? What is it that you know but do not remember? (I) You emerged, squalling, in a county hospital an hour away and you haven’t been farther since. (II) You roamed nearly feral through this landscape for years, a new queen for a forgotten realm. Do the gulls and badgers and hares now recognize your crownless head? (III) You almost drowned twice, the water mercifully spitting you back up on the rocks each time. You, the scraped-up, would-be mermaid.

But there is much that is outside the reach of your memory. Much that is not recollected to you. Your mother has said she is shielding you from things she wishes she did not remember. You have the sense that the past is a storm she is trying to outrun. She is trying to hide in a place that was scarcely imaginable to her before she arrived. She crossed an ocean thinking, ahead: blank slate. Clear skies. Or: a storm of my own choosing.

You, though, would not have chosen these bonedrench rains and gutpunch winds and the ceaseless cloud cover. You want nothing more than to leave the sea’s brink. To mirror your mother’s journey: go as far as possible, arrive at another edge of the world. But you cannot leave, or you cannot bring yourself to. Leaving means leaving your mother alone with the storm. If you were not there, you think she would let it swallow her.

What do you do with your days, then? You often walk to the trail that begins a couple miles down the coast and proceeds several miles farther to a historic lighthouse. In pleasant weather there are sometimes people out for the day, walking solo or in pairs or with dogs. This area of the country is renowned for its beauty. If you had not lived here as long as your memory, you think you could find it beautiful. You like to stand at the trailhead, by the crumbling stone wall that runs alongside, and rub a patch of furry lichen like a rabbit’s foot for luck. You are wishing for someone to talk to.

Today, two women walk by you at the trailhead within minutes of each other.

(I) One woman is carrying a hard hat and wearing a half-zip sweatshirt with a lighthouse embroidered on the breast.

(II) The other is carrying a hard black case and wearing a button-down shirt and khaki vest with numerous pockets.

Whom should you speak to?

- Lighthouse woman is tall and walks with purpose but slows upon noticing you scurrying to match her long strides. Hello, you say, beautiful weather we’re having. This opening is always effective; it is like the sun is the mutual acquaintance of everyone here and mention of her shining face is an instant form of connection.

Yes, the woman says, glancing at her phone. She seems a bit distracted. Hope it holds. We’re scheduled to start work in two weeks and can’t really afford to get rain delayed.

Right, you say. Fingers crossed, though around now we usually do see a turn. What are you working on?

The woman points to the lighthouse on her sweatshirt. I’m part of the project shifting Eddysedge inland. Before it falls into the sea, you know? Not a whole lot of ships trying to come in round here, but it’s one of the oldest on this stretch of coastline, so it seemed worth saving.

You, living in your house at the edge of the world, are familiar with erosion, a fatal disease eating away at the coastline. The waves devouring beaches, hollowing out the chalk cliffs. When you were a child, your mother would take you down to the beach by the lighthouse and stand at the far edge of the sand while you ran from her forward into the waves. You wondered why she chose to stand so far from you. Her tiny figure, silhouetted by the lighthouse rising up behind, striped red and white like the barbershop pole in town. Looking back from the water, that distance across the sand seemed uncrossable. Now, that distance is nonexistent.

Yes, you say, the sea is getting awful close. I’d heard about this project. Glad it’s moving along.

Is glad the right word, though? You aren’t quite sure. The lighthouse is mostly nonfunctional, now just an ornament affixed to the landscape. You’d overheard the estimated cost for the project once in town and your jaw dropped. No one is coming to save you, your mother, and your house from the sea, not for any amount of money.

Ahead, the tip of the lighthouse has become visible. The trail will fork, the left side traveling down to the lighthouse and the right continuing to follow the coastline.

Hey, the woman says suddenly. Are you from around here?

You nod.

Odd question, but did someone recently pass away nearby? The other day I noticed what looked like maybe a shrine by the trail a few paces on. Orange flowers, a small pool of water. I’m up here most days of late and hadn’t seen it before. Just wondering.

You are up here many days, too, and have never seen what the woman is talking about. You tell her no one around here has died recently, not that you know of. Not that you would know of much. But now you are wondering, too.

- Many Pockets Woman is whistling under her breath, something that sounds animal rather than human. She startles when she notices you and seems to grip her black case more tightly. You are somewhat used to this reaction, knowing you and your mother’s shade of brown is an unusual sight in this area.

Hello, you say. Beautiful weather we’re having.

The woman visibly relaxes at this. Yes, she says, it’s perfect. Best I’ve seen in the last couple weeks.

Indeed, you say. What brings you out here?

Well, she says, I’m an ornithologist. Specializing in sea birds. A few months ago I got a call saying someone had spotted a blue-bellied storm petrel nearby. That’s a bird we’d thought extinct for years. So I had to come see if this was a hoax or an amateur misidentification or the real thing, which would be amazing.

Wow, you say. Does sound like an amazing find if it is real. Do you have a sense yet?

A feeling, she says. Real. The other day I was down by the rocks past the lighthouse and heard what I was certain was its call. I made sure to bring my recording equipment this time. Haven’t seen the bird yet, though.

I hope you do soon, you say.

You aren’t sure, though, if you do hope the bird is real. If it is, what if it’s the last one of its kind? Would it know? You aren’t sure what’s sadder, the bird singing knowingly for only itself or unknowingly for only creatures that won’t understand it. Better a hoax, you think. Let the dead birds lie.

You pass the lighthouse, noticing a flurry of activity around its base, trucks and construction equipment amassed down the trail. The woman says she’ll have to turn off the trail soon to the rocky outcroppings where the bird has been known to roost.

Ironic, though, she says, after a short period of silence. If I do see the petrel, sailors’ superstition says that we’ll soon get bad weather. The birds are said to hold the souls of drowned sailors.

You give her a rueful smile. You have a healthy respect for superstition. It is an unknowable force like the sea, one it seems better not to cross.

Speaking of, the woman says, is this little altar thing up here for a lost sailor?

She motions to the left. Patches of yellow gorse coat much of the clifftops, so it’s difficult at first to see what she’s pointing at. Beneath one of the shrubs several paces away you see a small pool of water and a burst of orange flowers.

Nina Sudhakar is a writer, poet and lawyer based in Chicago. She is the author of Where to Carry the Sound (winner of the 2024 Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction and a 2024 Foreword INDIES Award) and two poetry chapbooks, Matriarchetypes and Embodiments. She serves as dispatches editor and book reviews editor for The Common and as a board member of the Chicago Poetry Center.