By HISHAM BUSTANI

Translated by NARIMAN YOUSSEF

Amman is not incidental. The sayl, the stream that patiently carved a path between seven hills for thousands of years, drew—as waterways often do—the din of life. It was somewhere close to here that the Ain Ghazal statues were found. Nine thousand years old, captivating in their simplicity, they seem to be about to speak as you contemplate their black-tar eyes, the details of their fine features, their square torsos and solid limbs.

A two-headed statue from Ain Ghazal, dated to approximately 7000 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of Osama SM Amin, commons.wikimedia.org.

Today, I follow the old path of the sayl around Jabal Amman (the “mountain” of Amman) and grieve. Nature spent centuries shaping a miracle, only for it to be destroyed in a few decades of aborted modernity. The sayl is now buried under concrete, layered under the junk and debris of “development.” All that remains of this ancient waterway are a few place names: Ras al-Ain (“fountainhead,” once a running spring, where water emerged from the ground and was fortified by multiple smaller springs on their way to Zarqa River); Saqf al-Sayl (“the stream’s ceiling,” where the water has been redirected into specially built underground canals, allowing the concrete and the black asphalt to rise and grow over the ground, creating a hideous ceiling for the beautiful natural scenery to disappear below, and die); and Ain Ghazal (“the deer’s spring,” where the statues were found, which used to be a picnic spot with trees extending their shade along the stream).

The sayl was paved over before I was born, but I see it still through the eyes of my father, who used to cross over it many times a day: en route to school at Sheikh Khalaf’s kuttab, to his father’s shop on Talal Street, or to the local oven, to which he walked with a wooden board on his head topped with pieces of dough ready to become the family’s bread. As he made his way, he might have looked down at some fish that caught his eye, or become momentarily distracted by the yells of his friends, calling him to join them, before they dove into the water.

A photograph of Amman, circa 1932, clearly showing the sayl and its path, al-Asbali Bridge that runs across it, and the three main buildings located on Mohammad al-Asbali’s land opposite the Roman Theatre: al-Asbaliyyah school on the right; the Amiri Diwan building in the center; and the Philadelphia Hotel, with its private tennis court, on the left. All three historic buildings were demolished to make way for the Hashemite Plaza. Source: Matson photograph collection, Library of Congress, loc.gov.

As a walk along today’s ghostly sayl shows, the disappearance of the stream has been accompanied by the vanishing of the city’s unique, historic architecture—stone buildings boasting tall windows, doors opening onto hanging balconies that jut out on metal beams beyond the building’s main structure—from all but the most dilapidated parts of the city. The crumbling neighborhoods of the old city, Jabal Amman, Jabal al-Lweibdeh, Jabal al-Hussein, Jabal al-Ashrafiyyeh, and Jabal al-Qalaa, all patiently wait for their turn to be crushed by bulldozers, to be maimed by inventive construction projects that get approved by officials who lack the slightest sense of taste and historical appreciation, or gentrified by and for the ajaneb, “expats” on the lookout for an “authentic” experience through which they can realize their orientalist imaginings of an exotic city stuck in a past they don’t know nor endeavor to explore; such ajaneb are content to dwell in their privileged bubble of English menus and English-speaking waiters, staying for months, sometimes years, without learning a word of Arabic, while failing to notice the astronomical rise in rent driving the locals out, bringing in their wake hotels, shopping spots, and studio-apartment blocks. Over the years, these neighborhoods, hidden from casual view by garish shop fronts, have become caught up in these, and other, dreams of greed and quick money. Through these “upgraded” neighborhoods, passersby resembling the aforementioned officials scurry through, looking away, almost fleeing, while others visit like tourists, descending from distant parts of the city as if from another planet.

Amman transformed from village to city at the beginning of the twentieth century, just two decades before it became the capital of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in 1921. Amman’s first municipal council was formed in 1909, six years after the establishment of its rail station on the Hijaz Railway, a massive Ottoman project connecting Damascus to Medina and, as a byproduct, connecting Amman to its surrounding communities in Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria). The city initially developed at a slow pace. Its diverse communities mingled and interacted in the swirling cauldron that distinguishes urban society. That was an open time, without the restrictions of borders or postcolonial nationalisms. Damascenes, for instance, known as merchants and specialists in certain crafts, whose presence and commerce were reinforced by the rail station, flowed in freely, and were the second group to emerge in Amman, maintaining their shops in the area surrounding the Grand Mosque and on Saadah Street, the central market of the city. These shopkeepers became some of the city’s notables, like Saeed Khair, the first mayor to preside over the city council after Amman was declared the capital of the country; Hassan (Abu Salah) al-Shorbaji, the chief merchant who was the final judge in merchants’ disputes; and Mohamed Ali Bdeir, who was responsible for bringing electricity to the city.

A bit farther from the mosque in those days, you would find Circassians, the first group to inhabit modern-day Amman, who came here as refugees in the second half of the nineteenth century to escape Tsarist Russia’s massacres in the faraway Caucasus Mountains. Being both peasants and seasoned warriors, the Circassians were settled by the Ottomans in key fertile points along the Syrian Hajj Road and the fertile lands that lay to the West, in order to help defend caravans of pilgrims from Bedouin raids originating from the desert areas. (The Syrian Hajj Road later became the Hijaz Railway.) The Circassians worked in agriculture, including cattle rearing, and some crafts, and were recognisable by their ox-pulled carts. The group arrived in several waves. The first Circassians to arrive were the Shapsugs, who dismounted from their horses and carts in 1878 and inhabited the Roman Theatre and the surrounding caves before they made the opposing slope of Jabal al-Qalaa (Citadel “Mountain”) their home, marking the neighborhood and its main street with their name. Their arrival marked the establishing moment of modern Amman, which was, until then, a khirbeh: a site of ruins marking older prosperous times,1 and farming-grazing grounds for local communities. The second Circassians to arrive were the Kabardians, who settled on the southeastern slope of Jabal Amman, where Quburtai Street still carries their name. Years later, a third wave settled southwest of the hill. The older residents of Amman were now settled enough and comfortable enough to call the Circassian newcomers and their new neighborhood Hay al-Muhajirin, “the migrants’ quarter,” a name it has continued to carry as other migrant worker and refugee communities—from Egypt, the Philippines, Sudan, Sri Lanka—come and go, even inhabiting the same houses occupied by the Circassian muhajirin before them.

The Circassians transformed early Amman from a khirbeh to a village, and their influence continues to be felt in the city. Ismael Babouk, the mayor of Amman’s first municipal council from 1909 to 1911, was a Circassian, and the Circassian sports club, al-Ahli, established in 1944, held, until very recently, top positions in Jordan’s basketball league; their dance troupes, especially Al-Jeel Al-Jadeed (“The New Generation”), have won admiration and acclaim; and the ceremonial royal guards, wearing their traditional Circassian attire, continue to be a distinctive fixture of the Jordanian royal palaces.

The next wave of immigrants to expand Amman and continue the site’s trajectory from village to cosmopolitan city consisted of Armenians fleeing Ottoman massacres during World War I. The Armenians gave their name to a neighborhood on Jabal al-Ashrafiyyeh that houses their church. Armenian and Circassian immigrants coincided with more local Balqawi families, both Christians and Muslims (Amman used to be a peripheral part of Balqa district, with its capital As-Salt), and Kurdish families (their madafa, which doubled as a guesthouse and a community center, used to be a notable landmark, as did Kurdi Hotel on Saadah Street, which later became King Ghazi Hotel). Families also came from Najd and Hijaz—including the family of the acclaimed author Abdul-Rahman Munif, who wrote about 1940s Amman in a masterly memoir, Story of a City: A Childhood in Amman (translated by Samira Kawar), and the Asbali family, who owned the al-Asbaliyyah School building, the largest and most famous primary school of the 1930s. The school’s “strategic” location next to the Emir’s Court meant that teachers and students alike were in daily contact with the country’s Hashemite emir, himself a migrant, newly arrived from Hijaz. Yet another influence were families from Bukhara (Souq al-Bukhariyyeh, the market that used to occupy the courtyard of al-Husseini Mosque before being moved across the street, is named after them), from Yemen (Souq al-Yemeniyyeh), from pre-Nakba Palestine (the Asfour, Mango, Belbeisi, and Malhass families, among others), and from other parts in the North, South, and East once the city had become an administrative and governmental hub. The story of Amman is therefore an old one: Revitalized by immigrants after a period of dormancy, the city then developed a centripetal force that drew migrants from many and various surrounding areas.

The Armenian church in Jabal al-Ashrafiyyeh (East Amman) overlooking West Amman. In the left middle distance, Le Royal Hotel on the 3rd Circle can be seen, and farther left in the background are the 6th Circle’s towers. On the right, the high-rise buildings of The Abdali Project can be seen. Source: KelseyArabicProgram.org.

Without the above diverse groups, there would have been no Amman. This mosaic of people, languages, traditions, and tastes created Amman, transforming it in four decades from a khirbeh to a city. All cities are birthed, shaped, and formed by migrants, but Amman’s “newness,” its continued evolution with more migrants (as we’ll see below), brings this point home acutely. Amman is the contemporary living proof that cities are created and built by migrants.

After a period of slow societal integration, from roughly 1878 to 1948, successive disasters in the surrounding region brought an explosion of Amman’s population and the urban reach of the city. More displaced families moved from Palestine (following the 1948 Nakba and the 1967 war), from Lebanon (following the civil war of the mid-1970s), from Syria (following the regime’s military attack and massacres in Hama in the early 1980s), from Kuwait (Jordanians were deported from Kuwait following the country’s liberation from the Iraqi invasion in 1990), from Iraq (following the American invasion of 2003), and from Syria again (escaping the violence that followed the 2011 uprising).

At the same time, internal migration continued from the provinces, since Amman enjoyed a relatively functional infrastructure, as well as administrative, health, and educational services. Now, Amman’s population constitutes forty-two percent of Jordan’s total population, which equalled 11.6 million at the end of the first half of 2024. Yet “no one is from Amman,” as people continuously stress, which is why everyone asks everyone else, “Where are you from?”—as if one is asking a tourist who is a stranger to the city. Such interrogations are an attempt to weave bonds through mutual alienation.

Amman is a therefore a city of immigrants par excellence, whether from as far away as Caucasus, Armenia, and Bukhara, or as close as Damascus, Nablus, Hejaz, and Yemen, or—even closer—from Salt, Madaba, Karak, Ajloun, and Irbid. These migrations have been both voluntary and obligatory and have produced different effects in these respective groups. Those who endured forced displacement and are unable to return sustain a vivid nostalgia for the home left behind. Even if they feel comfortable belonging to Amman, many migrants carry the burden of expulsion and the deep urge for (an impossible) return. When, on the other hand, a return to the departed land is still available, attainable, with no forced expulsion to feel bitter about or an occupation force or a “national border” to push against, migrants can gradually, fully belong to a new place.

The comfort of belonging was stronger, I believe, when the migration took place voluntarily and before the colonial division of the region, during which time a person was not “immigrating” but rather moving freely in their own “natural” habitat, a time before political borders installed (and instilled) the strict bases of loyalty and belonging. Perhaps Ammanis began to lose their collective community when various authorities adopted discourses that focused on “different origins and descents.”2 Such discourses maintained alienation between migrant populations, thereby hindering urban integration and development and leading to the popular notion that “no one is from Amman”—that is, that there is nothing called an “Ammani,” because every resident of Amman must necessarily be from, and be defined by, somewhere else.

Through writing, through my daily movement in and interactions with Amman’s cafés, staircases, winding alleyways, and chaotic streets, I am attempting to find a fulcrum point and exert a certain leverage, always expecting a pushback. Because, in my estimation, while Amman is vibrant and multifaceted, it contains an unusual tension: a suspended state between settling and leaving, coupled with the tension of an uncertain identity that has developed unevenly as Amman has shifted politically from the periphery to the center.

The first step of Amman’s rise in importance was its promotion from village to the capital of the emerging emirate, elevating Amman over much more prominent towns in Transjordan for sociopolitical reasons. This major transition planted the seed for rapid and steady expansion and evolution: the city became the center of attention; the hub of “development”; and the seat of administration, politics, and economy. Then, in 1946, the emirate of Jordan gained independence and became the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (the modern-day country of Jordan). All of these changes led people to move to Amman and prompted the city’s continued physical expansion, which has often occurred without planning or consideration of Amman’s unique urban environment.

In an attempt to meet the needs of its rapidly growing population, Amman expanded horizontally from the 1940s onward, especially to the west, eroding the fertile agricultural land and surrounding orchards, giving rise to Amman’s famous consecutive “circles”: roundabouts whose numbers also named the surrounding neighborhoods, chronologically registering the city’s expansion to the northwest as one counts from the 1st Circle, closest to the original city near the sayl, to the 8th, after which Jabal Amman dives into its border valley of Wadi al-Seer. Malhas Hospital (the first private hospital in the country) sprung up in what was once “the middle of nowhere”—the then-distant Abu-Sham orchard, now the 1st Circle. This was followed by the construction of the Islamic Educational College (1946–1947), which extended the urban sprawl to what is now the 2nd Circle, then Zahran Palace, the second royal palace to be built in Amman, and the street that bears its name, taking the upmarket neighborhoods farther west to the 4th Circle, until eventually—years later—the concrete and asphalt reached Bayader Wadi al-Seer and eradicated its wheat harvest (Bayader literally means “threshing floors”).

Contemporary Ammani society can therefore be likened to the experimental semi-fictional prose-poetry vignettes that I usually write: still in the process of taking shape; open to the horizons of transformation and change; heavy with conflict, contradiction, malformation, and potential; a laboratory where disparate elements are like the dispersed droplets of the bygone sayl, at times coming together, and at times meandering, as it once did between the hills.

The old Ottoman sabil on the corner of Saadah Street opposite the Grand Husseini Mosque in Amman (circa 1930), a unique structure later replaced by a building housing the Arab League Café, a prominent place of its time, with its distinctive high-ceilinged architecture, demolished in turn and replaced by a modern office building. Source: Fuad al-Bukari, Amman: The Memory of Good Old Times (in Arabic), Dar Sindibad, 2010, page 16.

Which is to say that development has been haphazard, at odds with Amman’s establishing value of openness, and has hindered inhabitants’ ability to interact with each other and with the spaces around them. The annihilation of the sayl was the gravest calamity to befall a city that was once called City of Waters, and it was followed by similar offenses. The government fenced off public plazas and squares (e.g., the Hashemite Plaza and the 4th Circle) in order to control assemblies within and around them, and destroyed older landmarks and urban areas under the guise of economic and touristic development. Over the years, we have lost beautiful buildings and important community hubs such as the al-Asbaliyyah School and the Philadelphia Hotel, both opposite the Roman Theatre; the Arab League Café by al-Husseini Mosque, my grandfather’s favorite hangout in the winter months, which itself had been built over an architecturally gorgeous Ottoman water sabil; Rainbow Street in Jabal Amman; and the entire neighborhood of al-Lweibdeh. Developers persist in believing the delusions of a cosmopolitanism that takes nothing from “modernity” but its husk and cultivates—instead of grains, or projects to encourage local development and production—consumer-friendly retail outlets.

Community harvest on land that falls inside the urban sprawl of Amman, as part of al-Barakeh Wheat project, which aims to revive the cultivation of native wheat and recenter it as food and as an economic and cultural asset, with the goal of achieving food sovereignty and gaining local control over food production. This field is located in front of City Mall, near Bayader Wadi al-Seer, northwest of Amman. Source: Photo by Rabee Zureikat, al-Barakeh Wheat. Received in personal correspondence, December 27, 2022.

That’s how we have ended up with the “LED curbs” (illuminated plastic road dividers) that have turned Amman’s squares and famous roundabouts into cheap relics of lost elegance. It’s also how architectural atrocities keep appearing like giant warts: Le Royal Hotel on 3rd Circle; the Abdali Boulevard; the deep, empty construction excavations; the unfinished and abandoned concrete skeletons that dot the city. Meanwhile, East Amman, the poorer, less serviced, and more densely populated and disorganized part of the city, housing the majority of its 4.9 million inhabitants, has remained the same: overlooked, almost invisible, its whole existence reduced to the building façades that happen to look out upon West Amman and its tourist destinations, freshly painted to protect the tourists’ sensitive eyes from poverty and provide a suitable background for their photographs.

(What we examine in this essay is not all of Amman, just the evolution of an erstwhile village that extended along the sayl on the low slopes of its seven hills and later expanded into what came to be known as West Amman. As a child of West Amman and its crumbling bourgeoisie, I will have to wait for the writing about East Amman to come from one of its own.)

Two personal experiences embody and distill for me the nature and speed of the city’s transformations. In 2015, I wrote the first draft of a short story called “Shooting at a Handcuffed City.” Recalling my early ventures on the public bus into Downtown, I describe my usual final stop: near the main post office building—what my father still refers to as the Post Office Plaza—where now the kiosk of Khizanat al-Jahith bookshop sticks out like a sore thumb. In the story, I couldn’t avoid commenting on the status of the iconic post office, which was adorned by large yellow signs with red lettering that said For Sale. A few years later, in 2022, as Guernica was about to publish the English translation of the story, I had to edit that sentence. The majestic old building was “now a Starbucks and Carrefour.”

One evening, also in 2022, I was walking in the 6th Circle area when the two towers that had been abandoned in skeleton stage since 2005, symbols of inertia and stagnation, suddenly lit up. Their giant glass façades were targeted by some kind of visual projection that blanketed the full height of those twin obscenities. I had to walk a bit farther before I could make out the content of the sequence of images, and then I was hit by its tragicomic audacity: the projection was celebrating the country’s achievements on the seventy-sixth anniversary of national independence. A celebration of success was spread across these colossal failures, which for years and years had been sitting idly atop what used to be a public park and the neighborhood’s only breathing space.

Who can blame me, then, if I take refuge in memory?

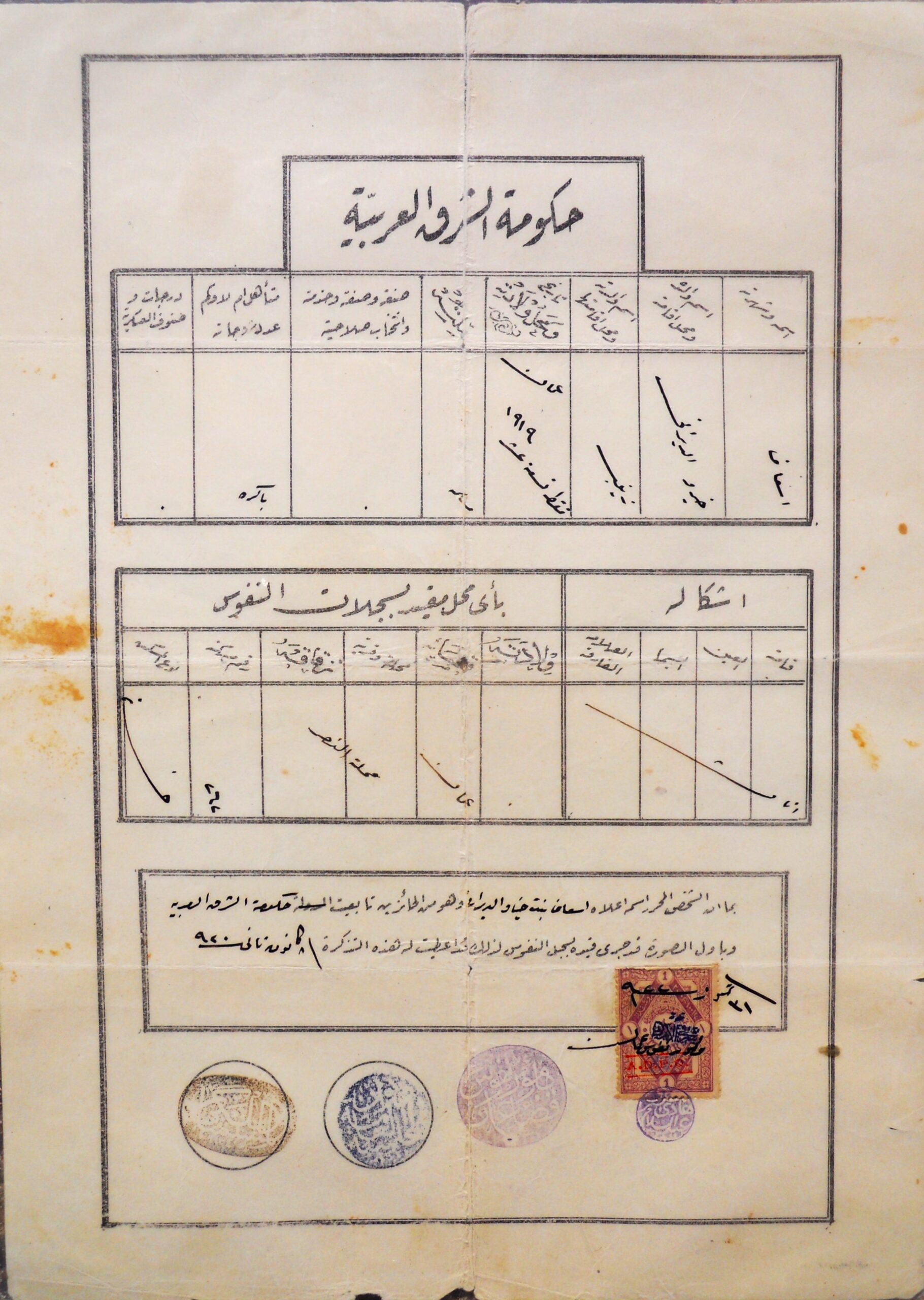

My memory of Amman is a tangled composition, in which the stories of three people are interwoven: my paternal aunt (Isaaf Khairu al-Diraniyyeh, born in Amman from the belly of Zainab Hasan al-Diraniyyeh, on an unspecified day in 1919, in Mahallat al-Nasr, house number 262, according to a birth certificate issued, at a later date, from the Arab East Government, under circumstances not remembered by her in detail); my father (Abdelfattah Subhi al-Bustani, born in Amman from the belly of Zainab Hasan al-Diraniyyeh, on the eve of December 11, 1937, at the family home located on the slope of Jabal al-Ashrafiyyeh and overlooking the sayl, halfway between the Hammam Bridge and the Roman Theatre, with the help of his grandmother Umm Saadi al-Diraniyyeh, until my grandfather arrived with the midwife while the sayl was brimming); and me (born in Amman from the belly of Amal Badreddin Salah, on the afternoon of February 9, 1975, at al-Ahli Hospital in Abdali, with the help of a doctor, while it snowed). The city’s crumbling reality is intertwined in my mind with a nostalgia that presses upon me, and perhaps on many others, a form of pathological attachment to what is gone and perished, to a book whose pages have closed forever.

Birth certificate of Aunt Isaaf Khairu al-Diraniyyeh, Amman, 1919. The Emirate of Transjordan, with its capital Amman, was created in 1921. Source: Author’s private collection.

My aunt, who possessed such rosy coloring that she was once told to wipe her cheeks with a wet rag by a teacher who refused to believe that their tint was natural, then punished her when it wouldn’t come off, was always haunted by the fact that her father pulled her out of school after the fourth grade. Had she graduated from the sixth grade, she would have become a teacher. This bitter regret lived in her until she died. Still, she was a lively and skilled woman who played oud at the “receptions” that city women hosted and attended, a skill she had picked up—along with smoking—from her stepmother (whom she called “Sister”), who in turn had most probably learned the instrument from her Turkish mother.

When my aunt got married, relatively late in life (in her mid-forties), she and her husband left Jabal Amman for Jabal al-Lweibdeh, but only for two years. She couldn’t bear the separation from her old neighborhood, and the two moved back to Jabal Amman. Invoking a deep sense of belonging to her original neighborhood and family house (in which she lived until the final days of her life), she referred to that temporary move as “being away,” and would say things like, “when we went away to al-Lweibdeh.” Today, my aunt’s grand house is abandoned, neglected, and up for sale.

To follow my aunt is also to follow the sartorial changes of most city women, starting with the fajjeh and mandil (in the 1920s and 1930s): two black pieces of fabric, a thicker one that covered the head and upper part of the body and a lighter see-through one that covered the face and was tied at the back. The lower half of the body was usually in a long skirt, or manteau, which left the bottom part of the calf uncovered. Later, around the 1940s, came the écharpe, a scarf that only partially covered the hair, leaving some of it visible at the front and the back, and was tied under the chin, until finally many women abandoned the head covering altogether.

Grandmother Zainab al-Diraniyyeh—wearing an écharpe—with some of her children, outside al-Bustani family home in Jabal al-Lweibdeh, circa 1949, with Mohammad al-Bustani to the right and Isaaf al-Diraniyyeh and Adib al-Bustani to the left. They are all in loungewear, which makes it a rare photo for the time. Source: Abdelfattah al-Bustani’s private collection.

Invoking memory in this manner seems to insist on holding the past up as more appealing. At the same time, a clear-eyed look at the old city with the eyes of now might lead us to curse its obsolescence. As Italo Calvino writes of one of his “invisible cities,” Maurilia:

… the magnificence and prosperity of the metropolis Maurilia, when compared to the old, provincial Maurilia, cannot compensate for a certain lost grace, which, however, can be appreciated only now in the old postcards, whereas before, when that provincial Maurilia was before one’s eyes, one saw absolutely nothing graceful and would see it even less today if Maurilia had remained unchanged.

Could that attachment to the memory of a time gone by be related to the unrepeatable joy of early discovery and first experiences? Or perhaps it’s the certainty of the moment lying firmly in the past that allows us to fully trust it, as it’s no longer able to cause any harm? Or is it the consciousness that has matured and feels finally able to sharpen its knives and dissect its present, invoking in the process a romanticized, exemplary past?

For me, every memory is a now-memory. It is a selective recollection that takes place in the present, for reasons that belong to the present, moved by questions that drag the past to the present in order to be answered. Memory employs the eyes of the present, a present charged with existential questions and a daily struggle for survival. Its summoning of the past is biased and premeditated. It compares its old, tired, wrinkled image to that of a naïve, awestruck, irresponsible, careless child-past.

I wonder what grace can be found in Amman today, outside of the old postcards?

Because, as in this essay, the images of “then” coexist alongside the city’s current “now” in a conjoined-disjointed weave. Together, they offer entry points to understanding the city’s iterations and transformations, to summoning the past within the present against a variety of backgrounds. We try to understand the present by placing an anchoring foot in the past.

And the past does resurface in the present, and the present sometimes looks like a rerun of desires born in the past, never fulfilled, resurfacing time and again, emphasizing the idea that we exist—city and city-dwellers—in a moment of stuckness and stagnation that also doubles as a moment of regression. The world and its affairs are built on unrelenting movement; those who remain standing get left behind.

Hisham Bustani is an award-winning Jordanian author of short fiction and poetry. Much of his work revolves around issues related to social and political change, particularly the dystopian experience of post-colonial modernity in the Arab world. His fiction and poetry have been translated into many languages, with English-language translations selected for Best Literary Translations and Best Asian Short Stories, appearing in the Kenyon Review, The Georgia Review, The Poetry Review, and Modern Poetry in Translation. His most recent book is The Monotonous Chaos of Existence.

Nariman Youssef is a Cairo-born literary translator based in London. She has led and curated translation workshops with Shadow Heroes, Shubbak Festival and Africa Writes. Her recent translations include Mo(a)t: Stories from Arabic, Inaam Kachachi’s The American Granddaughter, Donia Kamal’s Cigarette Number Seven, and pieces in The Common, ArabLit Quarterly, and Words Without Borders. Nariman holds a master’s degree in translation studies from the University of Edinburgh.