Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

This month, our online contributors CHRIS JOHN POOLE, JULES FITZ GERALD, and LAURA NAGLE recommend three inventive, deeply human books with stories that traverse two oceans—from Japan, to Mexico, to Norway.

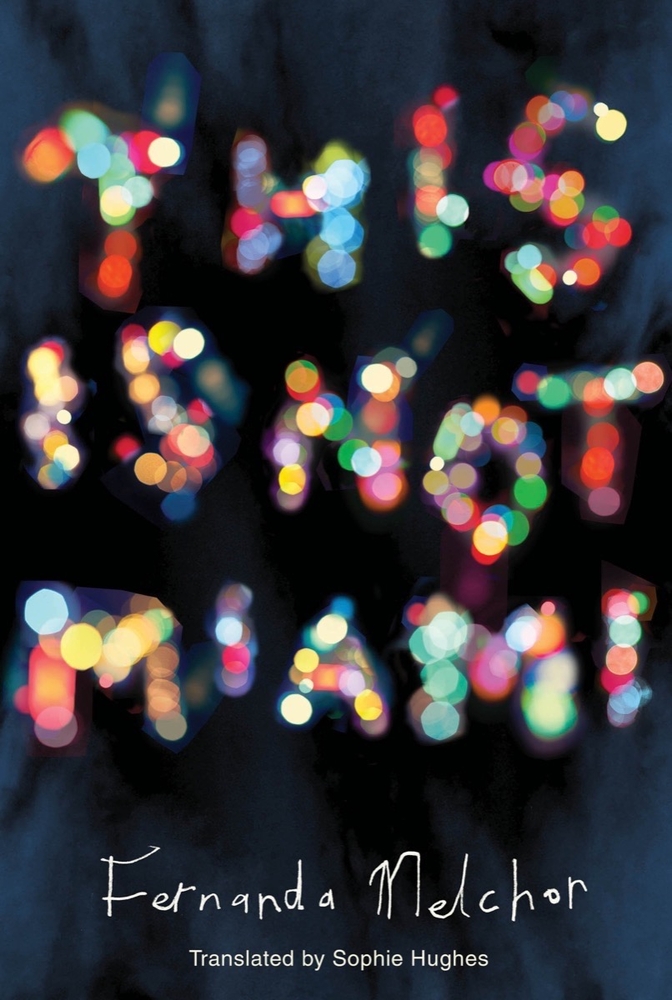

Fernanda Melchor’s This Is Not Miami (trans. Sophie Hughes); recommended by TC Online Contributor Chris John Poole

In her author’s note to This Is Not Miami, Fernanda Melchor writes that “to live in a city is to live among stories.” The city in question is Veracruz, Melchor’s birthplace, a city of cartel violence and political corruption; ritual magic and cold, hard truth. Veracruz’s stories, meanwhile, are those which are gleaned from—and imposed onto—its grim realities.

The stories in This Is Not Miami are crónicas, a genre with no direct equivalent in the Anglophone canon. Crónicas mix reportage and fiction, in a manner akin to gonzo journalism. They favour subjective accounts and firsthand experience over hard data and rigid chronology. Melchor’s crónicas collate rumours, folk myths, and personal narratives, injecting reportage where necessary.