I walked out there

between the boiling tides,

where the sky turns into a horizon

and the whales go global,

swimming like happy boulders

in an asynchronous landslide.

I walked out there

between the boiling tides,

where the sky turns into a horizon

and the whales go global,

swimming like happy boulders

in an asynchronous landslide.

Driving from Dunmore East about halfway

between Dublin and Cork on one of those narrow

cattle roads, we thought we were again lost

in the overcast and intermittent rain

O Lynx keep watch on my fire he had written in Pisa

and Dryad he’d called her a long time back and she

thought the new subtlety of eyes was probably hers

dove sta memoria when she read it in his prison poems

in her Künsnacht sanatorium . . .

i.m. Charles Olson and Thomas Wolfe

so you’ve only a museum now

and not a college at all

although I understand the buildings still exist near the town

where religion has reclaimed the real estate that

John Rice took for the muses after he scandaled at Rollins

lecturing on the classics in his jock.

The old men who scrambled out at last from behind

some rocks and trees below Poseidon’s great Horse Hill

That they called kolonos hippios and was famous for the rider

whose immortal name these coloni still bore and was

Still guarded by Eumenides of black night and bright day

Had a kind of tabloid curiosity

were men

in wool or gabardine. They named

the mountain road

sinuous for its crawl-by-crawl

among stone outcroppings.

In the beginning, the Lord God created man in Adams County, Ohio, just north of Peebles and south of Chillicothe.

On the very western edge of the Appalachians, in the craggy countryside of southern Ohio, the three branches of a small river called Brush Creek converge in a valley lined with pitch pine and chestnut oak trees. A steep rocky bluff rises one hundred feet above the riverbed. And on top of this bluff lies an ancient mound of soil, waist high, built in the shape of a serpent. The snake’s head—120 feet long and 60 feet wide—faces the north end of the bluff, overlooking the river. From there, the snake’s body stretches southward 1,300 feet in loose waves, and ends in a tightly curled triple spiral.

By TED CONOVER

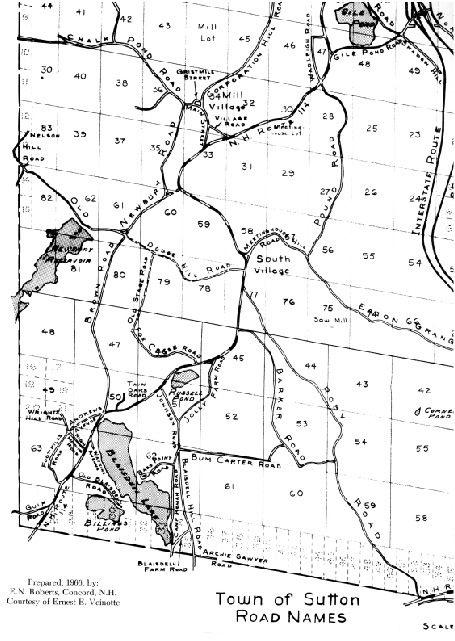

If it weren’t for the detailed map in my hands—a page of the New Hampshire Atlas and Gazetteer, from DeLorme, with the small state divided up into more than thirty spreads—I’d have had no idea that a road existed here, half a mile from our house. And in fact, the atlas has oversold it: Brown Road does exist, but not in a condition where you could drive a car or even an SUV down it. Nor a mountain bike, unless you were hardcore and could lift it over fallen trees, slide it under branches, and skirt some soggy bogs.

By LAUREN GROFF

My wife has always been a kind woman, but during the six months when I was in prison, her kindness grew to be a firm, beating thing. She called me every day and sent small and constant gifts. She brought our children to visit, and the kids soon lost their fury and held their smiles behind their palms, watching me with a kind of incredulous wonder. My wife was so graceful in the newspaper photographs and interviews, shining on me so much of her own quiet light, that by the time I was released I was more a figure of pity, even a scapegoat, than the monster I’d been painted as throughout the trial.

It was August when a young balding man and his fat mother appeared behind the counter of the corner deli. No grand opening. The previous owner, Herman, had cleared out one night. Gambling debts, neighbors said. Herman’s Deli had always been a beat-up place on the corner, and the new owners didn’t seem very ambitious either. The pushpins that held Herman’s rick-rack borders were still on the shelves—half of which were bare and unlined, exposing warped wood. The glass case that held the cold cuts was smudged even on that first day.