I said nothing and thought

of the Foro Romano—

its basilicas, temples, arches—

imagined being by the Lapis Niger

confessing by the tomb of Romulus

and listening to Livia.

Issue 28 Poetry

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Rome, New York

after Austin Araujo

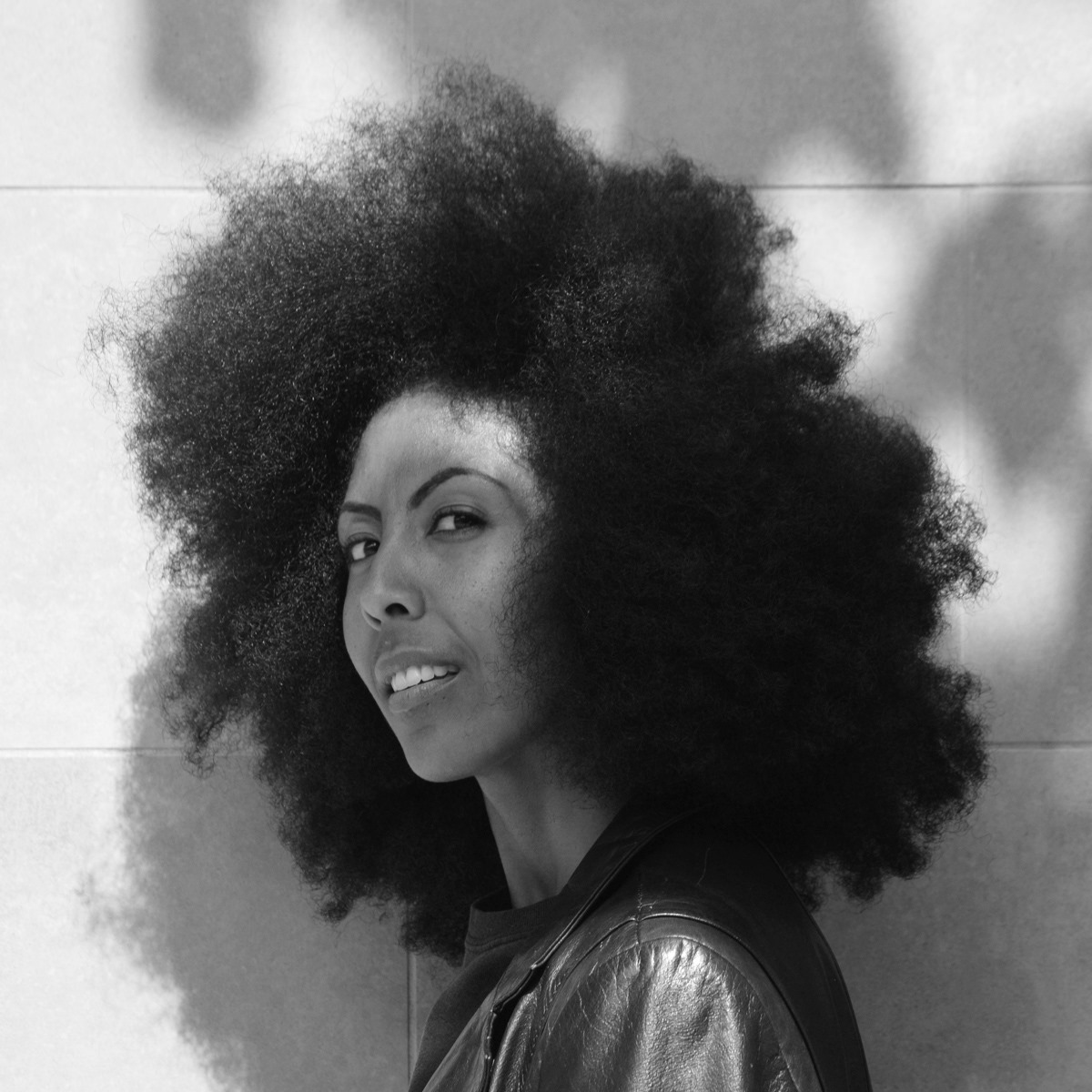

In my favorite picture of you, the hair blown across

your face, obscuring your face, it’s easy to make out,

deep in the distance, the hangers of the air force base

classified as a superfund site, a sprawling huddle

of buildings expanding out into the extent of the valley.

Prelude

Was it all simply adornment,

watching the rain fall from the sun,

or the mourning dove that carried

the wallet-sized photo in its beak?

Looking back, it was true—

I had stopped seeing the beauty in it all,

living from moment to moment,

looking to be granted some small sense

of pleasure, as if by respite or charity.

In Montgomery County

Maryland, 2020

My partner wears the panopticon,

and I carry the rope. Hungry

for the rush, the chase, we locate

the missing black calf

about two-tenths of a mile

from East Silver Spring.

He’s wearing a long-sleeve

jersey T-shirt, navy blue jeans.

Collaboration

We are stretching towards each other,

words tangling. The words can’t always

be torn apart. Sometimes you

are ти. Sometimes we touch.

Diorama 1871 (say her name four times)

Jane loved her and often thought of her skin.

Its misleading surface area always moved her, how it wrapped around

and became infinite.

Silent Spring

I saw a barn owl staring out from a telephone wire

driving down the road with the sky looking

like the edges of the newspaper we crumpled

into balls to light the woodstove

Maria Josep Escrivà: Poems

By MARIA JOSEP ESCRIVÀ

Translated by PETER BUSH

Who

Who has ever felt the shock of a brook

being sucked dry by the warm earth?

Who has ever felt the shock of the last

house falling apart in the mountains, mineral

corpse, stone by stone, bone by bone

of each man banished?

Iqra

Winner of the DISQUIET Prize for Poetry

By IQRA KHAN

Watch the poet read from this piece at our Issue 28 launch party:

I begin as revelation. As explosion of glottal light against silence.

I am again asking for directions to the Haram, my ankles fluent in Arabic.

I am again asking for direction, ya Haram, my ankles flowing with Arabic!

Hagar, watch how God transforms this wilderness to civilization.

Roadside Blackberries

By ZACK STRAIT

There were other vehicles moving through the darkness behind us. But we didn’t notice. We forced our bodies into the brambles. We stood on our tiptoes, reached high above our heads like we were greedy for the stars that night. But we craved something attainable, we thought. We thought our need was for the wild summer blackberries. But we were foraging for another memory to sustain us through the evil days to come. And as we ate, the past ripened in clusters for us there among the thorns. I don’t know what my father thought about then, as we filled our bellies with those dark jewels, but I could almost taste my grandmother’s fruit cobbler. The blackberries, I remember, were perfect that night. They were plump and sweet. The juice didn’t stain our fingers or mouths. We ate and ate. How wonderful, how the earth offers such goodness to us without cost. And how awful.