Rosa Castellano (left) and Diamond Forde (right)

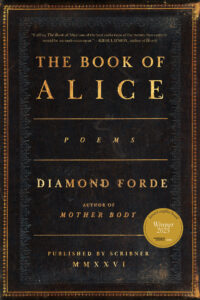

DIAMOND FORDE’s newest poetry collection, The Book of Alice, was the winner of the Academy of American Poets’ James Laughlin Award and was recently published by Scribner Books. Her first poetry collection, Mother Body, was a Kate Tufts Discovery Award nominee.

For this interview, Forde connected with friend and fellow poet, ROSA CASTELLANO, over Zoom. Castellano sipped coffee in Richmond, Virginia, while Forde sat in her bright office in Raleigh, North Carolina. Her dog, Oatmeal, curled at her feet. The poets discussed navigating family memories, the Bible, and Scribner selecting Forde’s manuscript during their open call for poetry manuscripts in 2023.

Rosa Castellano (RC): Diamond, how exciting that your beautiful collection, The Book of Alice was selected for publication by Scribner! I heard they reached their cap of 300 manuscripts in just three minutes!

Diamond Forde (DF): It’s a testament to how absolutely terrifying the landscape of publishing is right now, especially for poetry, that we were all so deeply desperate for this opportunity. And that is a responsibility that I hold with this book—knowing that there are so many incredible poets who also deserve this opportunity. I’m trying to do what I can to make this book successful because I want these publishers to invest in poetry. I want to prove that poetry is necessary and vital, and I want more opportunities to open up for other writers.

RC: Well, you are definitely doing your part for poetry with this collection—it’s a gorgeous book! While this is largely the story of your grandmother Alice, it often felt like I was reading the “Book of Diamond,” and then by extension, the “Book of Rosa.” I imagine that will be true for a lot of your readers. There’s this idea that stories belong to the teller until they are told, but in The Book of Alice, you push that idea to make readers aware of the multiple intersecting stories at play. Your book teases out ideas of lineage and links them to storytelling in a way that offers a blueprint for belonging. Readers can see, and sometimes feel, themselves inside Alice’s story. Could you talk about what it was like to bring Alice’s story to the page?

And as this book becomes part of the energy I put into the world, it will help change and construct and move people, too. Although maybe that is romantic and ambitious—an audacious idea, but fuck it. If white men can be those things, I can too.

DF: Thank you for that. One of the first poems I wrote for this book that showed me that I had a book was “Creation Myth,” a poem about my grandmother making biscuits that came from a story handed down through my family. My grandmother was a sharecropper’s daughter working the cotton fields in the Carolinas, and because she absolutely loathed it, she promised herself she’d marry the first man who asked her.

Then my grandpa fell in love with her. I mean, she was just this gorgeous woman with super long hair, and when she met him back in the late forties, early fifties, she was like, “I have to prove that I’ll be a capable wife,” and so decided she’d make biscuits. I really liked the idea of biscuits being the foundation of who I am, that I exist because of her biscuits. So, I took this story given to me with so much fantasy and transformed it into a kind of origin story, a kind of creation story, because it is—it’s the moment my grandmother constructed her own destiny, and in so doing, constructed me and the legacy I get to carry forward.

A lot of this book is me trying to understand who my grandmother was, to better understand who I am. I want to know the legacy of how my grandmother was raised, and how she raised my mother; all of those things are carried within me. A big part of what I was trying to accomplish with this book is thinking about all the energies I’ve collided with that have constructed me.

So there are times when the book gives voice to women outside my immediate family, literary figures like Sethe, for instance, because Toni Morrison’s Beloved fundamentally changed me. I’m trying to stretch the idea of family, opening up possibilities as energies collide in this book. The dedication of this book is to all of the children of Alice, and I don’t mean just my family. I mean all of us who find ourselves in kinship with Alice and her legacy, with the legacy of the characters in this book. And as this book becomes part of the energy I put into the world, it will help change, construct, and move people, too. Although maybe that is romantic and ambitious—an audacious idea, but fuck it. If white men can be those things, I can too.

I used the King James Bible because it’s the only thing I have to remember my grandmother by. She loved that book. It is, I think, her first and only true understanding of poetry.

RC: Yes! This book is audacious, biblical even! And that audaciousness seems intentional, from section titles like Genesis, Lamentations (or Leviticus), and Revelations, to the poems formatted with verse numbers like the chapters in the Bible. Can you talk about some of those choices?

DF: Yes, when I first started, it was formatted with chapters and verses like in a King James Bible. But then, as the book got bigger and more unwieldy, I realized I was boxing myself in, and that format became harder to pull off. So, I had to let that go, but I wanted to hold onto the ghost of those formats, keep that allegiance to the style of Bible verses. This idea is present in poems like “The Sow Speaks to Noah” or in the red-letter font included in the first edition—which is meant to represent those moments where my grandmother is speaking. I really wanted to utilize the hallmarks of the Bible, while also creating something new that functions as a poetry book.

And I used the King James Bible because it’s the only thing I have to remember my grandmother by. She loved that book. It is, I think, her first and only true understanding of poetry. And to understand her better, I spent a lot of time trying to recreate the conventions of my own particular Bible, trying to speak to and commune with the Word the way that she would’ve seen it.

RC: Was making the shift away from the structured biblical version of the format difficult?=

DF: It was. I went through a couple of iterations and sat with versions of what the chapter titles would be. Originally, I didn’t have five sections; I only had four. So: Genesis, Exodus, Lamentations, and Revelations. And before that, it was only three: Genesis, Exodus, and then Revelations. I knew I wanted the collection to be more in conversation with the Old Testament than the New. I sat with that and tried to figure out where I would fit. And it was the desire to stretch the idea of generations that led me to Daughters, except, unlike the Bible, I didn’t want a lineage of sons; I wanted to think about a lineage of daughters.

RC: I love that! And I think you’ve really done that here. Could we talk about the way these poems investigate grief?

DF: When my grandmother died back in 2007, I didn’t have the safety to grieve her, so her death was never fully real to me. This book, in many ways, is me grieving my grandmother’s death a decade late. I think the first time it hit, I was at the University of Alabama, where I got my MFA. We went out to dinner with Ross Gay right before his reading, and he was telling us about this song, Bettye LaVette covering Chaka Khan’s “Love Me Still,” and he ended up playing the YouTube clip for us in the restaurant and I was listening to LaVette and the way her voice warbled, it reminded me of the way my grandmother used to sing. And it hit me, hit me hard, that grief. And then I’m barely holding it together, trying to push it down until after the reading, and when I get back into my car, I don’t even leave the parking lot. I pulled up the video again, played the song, and I heard her voice again. And this voice that I hadn’t even had the space to realize I had forgotten came back to me. I just started bawling. I wrote a poem about that moment. But again, I still wasn’t really in a safe enough place to process, but I wrote the poem, and that was my entryway into grief.

My grandmother did not tell my mom that she loved her, which is a devastating thing to learn as an adult. But I don’t think my grandmother ever told me she loved me either. And that is its own kind of grief. I don’t know if she even knew how to love really, if she even believed in it anymore. And that’s something to mourn, too. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the first poem transitioning out of Lamentations is an “Addendum from the Savior,” where I talk about Emmett Till, which explores a kind of diasporic grief.

In this book, I’m navigating all of the things we are simultaneously grieving, from ecological to the historical, while also reclaiming power in the act of writing. And through understanding and knowing that my grandmother and I can never have any of the conversations I need to have with her.

So yeah, a multifaceted grief constructed who I am, but also, it’s my responsibility to break from it. I get to decide who I am at the end of the day. So, there’s grief here, but also Revelation.

“But the footnote is a beautiful way of conceptualizing the margins, and there’s power in ascribing my grandmother’s abusers to footnotes.”

RC: How you transition readers from Lamentations to Revelations is so powerful. And there are several poems in the Revelations section, the last section, that I’d love to talk about. After reading “Rememory,” I immediately pictured myself teaching it. This collection is full of poems I’m excited to share and teach, from the recipe poems to “What I Shoulda Said When You Asked Me…,” to the poem you wrote to a Diamond in an alternate universe (“Record of Deaths: Diamond Forde”). In “Rememory,” the poem has footnotes that operate as a separate poem in conversation with the original poem on the page. It reminds me a little of a Burning Haibun. Is this a form you invented?

DF: I don’t know if I could say I invented it, because other poets have also used footnotes this way. But the footnote is a beautiful way of conceptualizing the margins, and there’s power in ascribing my grandmother’s abusers to footnotes.

It’s part of my way of trying to reclaim my story and say what my story gets to be. Because of that cycle of violence and the way legacy is carried—I can say with confidence that my mom also knows abuse. But I can decide that that narrative stops in me, that I will not tolerate abuse, that I won’t participate in this cycle of violence. I refuse to be that continuation, because I get to say to those who have tried to wound my generations, have tried to wound my grandmother: you stop here, you become just a footnote.

Maybe the most difficult part of navigating this book and my grandmother’s history, my family’s memories too, is realizing my grandmother never knew a man who didn’t hurt her. Many of us intimately know that pain, but that pain can stop with us. The haunting can stop with us. At least, I want to believe it can.

A big part of what I wanted to do with Revelations was revel in our power. So this poem is one of those ways that I did that. And that transition from “Rememory” into the next poem, “Candied Yams or What to Do When Another Man Hits You,” is trying to acknowledge again, the kinds of violences that both my family and I have had to navigate.

Everything I write is just me trying to teach myself how to survive. There are a lot of ways life and our climate, and the systemic genocide of all of us is trying to destroy our ability to survive. And I think I have a hard time convincing myself that my survival is possible and necessary. So, the page becomes the place where one imagines that survival can take place.

I give myself permission to be on the page in ways that I could never give myself in this world. I’m skeptical of saying the “real world” because what happens on the page is also real. And so, I am trying to create a reality in deference to the very first poem in the book.

RC: Wow, yes. And when you say, “I am actively making something a footnote,” I am reminded that despite poetry’s ethereality, there can be something physical about the experience of reading. Throughout your book, you invoke the body by asking readers to participate. We have to turn the book sideways, or imagine the sound of Alice’s voice, and in the last poem of the collection (“Dance With Me, Alice”), there’s a dance with Alice that feels like a hug. Your collection offers readers a way of seeing and experiencing what’s liminal, and that allows for a kind of belonging that puts us and our lineages on the page with you.

DF: Pain is an inevitability of embodiment, but it doesn’t have to be the only consequence of embodiment, and I love a good stanky, sweaty, musky body in a poem. I love bodies that affront us with their physicality. I can think of no greater, sweatier joy than dancing in the club, this collision of bodies together. There’s a power in being able to command your body in the fullness of its joy. I mean, just the music, the things that live through you. It’s a communal process that we are all undertaking in a moment of ecstasy together. It’s fantastic.

I teach Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic,” and her engagement with eroticism as the fullness of pleasure, of the joy that we share with one another, is what that poem is inviting us into, this fullness of eroticism to say, here we go, let’s dance, be free.

Dr. Diamond Forde is the author of two poetry collections, The Book of Alice, winner of the Academy of American Poets’ James Laughlin award, and Mother Body, a 2022 Kate Tufts Discovery award finalist. Forde has received a Doctorate in Creative Writing from Florida State University, an MFA in Creative Writing at The University of Alabama, and a Bachelors in English at the University of West Georgia. Her work has received recognition in the Furious Flower Poetry Prize, in Great River Review’s Pink Poetry Prize, and has earned her a Ruth Lily Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg fellowship. You can find Forde’s work in Poetry Magazine, Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, Obsidian, and elsewhere. Forde serves as the Interviews Editor with Honey Literary, as an assistant professor at North Carolina State University, and as an avid lover of fish and grits. Find out more at her website: www.diamondforde.com

Rosa Castellano is the Literary Arts Director for Sundress Publications and co-founder of RVA Poetry Fest. Her writing appears in Poetry Northwest, Guernica, Bomb, Write or Die and Lit Hub among others. Her debut poetry collection, All is the Telling, is available now from Diode Editions. Originally from Tampa, FL, she happily calls Richmond, VA home.