Excerpted from The Church of Mastery, a finalist for the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing 2025

Or, to use some expressions which are nearest the heart of the Masters, it is necessary for the archer to become, in spite of himself, an unmoved center. Then comes the supreme and ultimate miracle: art becoming “artless,” shooting becomes not-shooting, a shooting without bow and arrow; the teacher becomes a pupil again, the Master a beginner, the end a beginning, and the beginning perfection.

—Eugen Herrigel, Zen in the Art of Archery

Given all their invisible stresses, all their accumulated ambitions, and the narrowness of their paths, the Freedom Riders in Pursuit of Veracity agreed they needed to relax to prepare for their journey down South; relaxation is not a luxury, it is a requirement. America has a problem with Black people relaxing. Or behaving like a boss. That’s why William would spend an entire day now and again by himself like Jesus in the wilderness. He’d meander through the weirdest stacks of a downtown bookstore just to wander. Who knows what Language was destined to change you? That’s why he took up cricket with René from Port of Spain. Why he’d take Rowena out to restaurants they could not afford to order dishes he could not pronounce—spine straight, risking glares.

Glyn Moore and Birdman—a Buddhist in Harlem!—has them watching samurai films in the basement of Harlem’s Trinidad Barbell. Turns out a dungeon can lead to a deeper dungeon; ask Dante. And just like so, this world opens up like an easygoing lotus, unbothered by the lake of mud in which it blooms. Sensible and still, a lotus possesses its own schedule. The East. Who said “The East” is east? Who said “The West” is west? An even more egg-headed, less employed version of himself would take apart all the problems with the adjective “Oriental,” admittedly pretty—a dactyl.

William is awful at watching movies! This is a sin. Who installed that light beam? The projector screen? That beam of white light reveals particles—dust. When nobody is looking, William reaches for light particles like they were fuzzy dandelion seeds floating in the sky after just the right puff. Is William touching Light? He’s touching Light. William’s mind goes off in too many directions, but the truth is, as summer approaches, and plans become realities, visions, bus tickets and living wills and the possibility of arrest, William realizes his mother is correct: his reasons must be stronger than his hesitations. Than his excuses. The first lines of William’s poems are always messy; he often excises them like a surgeon, time of the essence. Writing those first lines, he feels like leaping—into what? Where?

Here is the plan. Mid-June, the Freedom Riders in Pursuit of Veracity will pilgrimage to François’s family home in Washington, D.C. After a week praying and preparing with students at Howard, they will ride down: into Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, until they reach Florida. William craves crawfish and thick soups. Buckets of shrimp, unshelled in ice, spicy with horseradish, tart with fat Eureka lemons. William made Rowena laugh: could this great odyssey be for their appetites?

Silly, Rowena whispered. He knew when her laughter hid nerves.

He looked into her, looked away, and she knew what he meant.

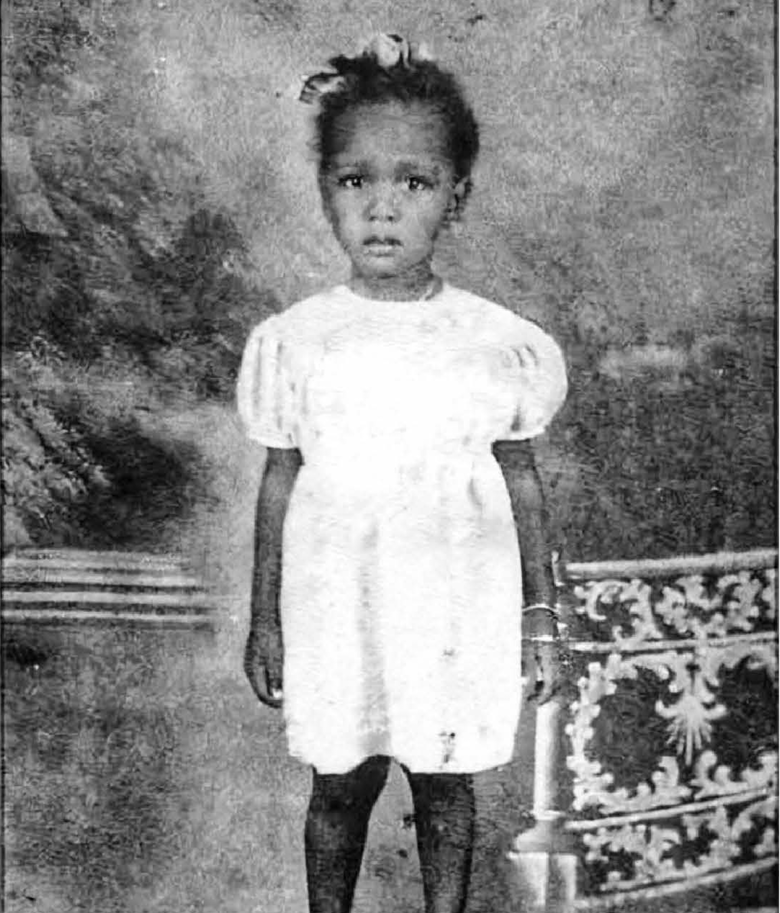

They must make it to Orlando, to Summer Park, to interview Abel. To understand his quiet, his history.

No agenda, François affirmed. Let Abel’s words shape his story.

And William nodded; the bus is their chariot.

René is half Black, all Hindu. What is René’s “why?” They have just finished watching a film on the masterless swordsman, Miyamoto Musashi. It was directed by Hiroshi Inagaki—who does not look like a samurai. What should a samurai look like?

Toward the end of the movie, William’s eyes landed on René sitting pensively in the front row. René looks like a samurai: eyebrows furrowed, observation fixed no matter what, or so it appears, on the causal dimension. The son of a tailor, René could not lose his scholarship—every day at Columbia, he must justify his position. William wonders how much of René’s work is tied to raw interest. How much of his work has to do with remaining in America? René has no choice but to be excellent. If René fumbles his arrow, once, what might be the translator’s finest arrow—blinks too long—René would be on the road. When William sees René, first things he thinks about are:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- logophilia

- cricket

- India.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

(René has to be more . . . )

The dozen Freedom Riders in Pursuit of Veracity climbed the steps to the gym where they were eating potato chips, sipping lime soda. Saturday, late March, eleven p.m. William and René are alone. William can hear his friends upstairs chatting: about the daily practice of the sword, stray gossip. Picong. René—still but not strange—stares at the blank screen.

William really does suffer from laughable concentration. Two Saturdays ago, the Freedom Riders watched a samurai film from the thirties—all swordplay, silver glinting on the projector screen. William found all the showdowns, powerplays boring. He closed his eyes, heard himself snore. When he opened his eyes, rubbed them, he saw three figures in kimonos, straw baskets covering their heads.

Beggar monks, Birdman explained. Komuso. In the film, all these warriors are fighting; the monks keep playing their flutes . . .

Ever-conscious of the vastness of these cosmoi, the sweep of the past, the unforgivingness of the future. Memento mori. The Japanese government banned the monks’ flute-playing. What did the governors fear?

René is built for cricket, for swordplay. Six-foot-five, precise fingers, forearms lightly veined. René’s manners remind William of that sadhu, Hanuman Singh, Abel told them about, guided by some beautiful Indian hymn ever chanting beyond his crown . . .

William channels Miss Johnson’s directness, joins René in the front row. René jumps.

“Sorry, brother,” William says.

“Didn’t know anybody was still here.”

Is there a way to be blunt without being mean? William pays very close attention to the music of his words. How can he not? Some conversations are poems; some conversations, you’re just trying.

“Can I ask you a question, brother?” William asks.

“Sure thing.”

The basement is dark.

“You pushing so hard at Columbia,” William says. “Down South: why you coming along?”

“Brother, I could ask you the same question.”

The chatter upstairs diminishes. Somebody drops a plate—a cup?

Broom in the closet, Birdman says.

The projector screen, still blank. William is talking to a man who holds onto so many secrets, so many stories, a man who has decided to devote his one, precious life to steering a single boat, cruelly tossing any weight that does not contribute to its forward momentum.

René’s care, François told William at Abraham’s Café. Brother, I’ve never seen anything like it—his care.

René is constantly translating other people, their words and silences. Every person is a text.

“My mother,” William tries. “Do you know what she asked me?”

“What’s that, brother?”

René folds his prayerful hands atop his right knee. Despite all his discipline, the translator never forgets his graciousness—does not want his friend to feel rushed despite the late hour.

“Before we do any of this work, my mother said, we need to write down our reasons. And if they are not strong enough—” William says.

“What?” René asks.

“We’re gonna fail,” William says.

René looks more deeply into the movie screen, still infinite, still blank.

“Your mother,” René says finally, “she’s a very wise woman.”

How slowly, consistently René’s translations must progress. How patiently, how methodically René—despite all his pressures—calmly yields to the gated metrics of sutras. Their rhythms are clearly his guides. How long does René spend determining whether “alacrity” is a more suitable noun than “swiftness?” René must unnerve his colleagues. We are frightened, profoundly, by people committed to Silence remaining silent.

René turns to William, looks into him.

“My ‘why . . . ’” René whispers, “you are inquiring about my ‘why . . .’”

And René allows the word why to enter some subtle chest René alone locks, unlocks. René receives the syllable. Tastes it.

“You know what happened to me, William, when I discovered Sanskrit? I imagine the same thing happened to you when you discovered poetry. I felt in control. A control I never before felt. On my maddest days, I’d feel invincible. Like the march of the universe, the music of the spheres flowed through my pen. That’s the kind of feeling a coolie man is trained not to honor. In subtle ways. Go back to slouching, a bully commands. Just with his stare. But that feeling of invincibility—immortality, invulnerability, importance: Voltaire ate that feeling for breakfast. Goethe . . . ”

“And Tagore,” William says.

“Some days, I envy their flow—their momentum,” René says. “But then I learn from those men: never dishonor the certainties.”

“When did you meet your guru?” William asks.

“I was thirteen,” René says. “Pandit Jambavan returned to Port of Spain. He had spent twenty-three years with his guru learning Sanskrit in London, then India. The pandit wanted to spend his remaining years in Trinidad teaching children this language the world didn’t care we forgot. But the pandit cared. Man, he cared so deeply. And we knew what he was teaching us was important even if we didn’t know all the reasons why. Something about the pandit’s care, its genuineness—this care, it was in his eyes, his words, you see, William—led me to believe in Sound, to worship it, and here was this language the pandit was gifting the six of us at his lotus feet to return to something I don’t know: pure.”

“Pure?” William asks, thinking of Hemingway. “Like struggling for your catch?

“Man, those first days I got it—when I really understood Sanskrit, could hear it, really hear it—I could feel this power surge through me. It felt that way because when I started transcribing short passages—from The Mahabharata, The Ramayana—”

“Epics . . . ” William whispers.

“Yes,” René says, smiling. “William, my hands would tremble when I let the work sink in, flow—God, what I was transcribing. And I could not stop! I was led. I suppose you could say: I became obsessed. Am obsessed. It’s not normal. I know this. I had to remember to nurture friendships, to bathe. One day, when I was seventeen and preparing to apply to university, my father pulled me aside and said—”

“What did he say?” William asked.

“Said: Son, you walking different. My posture. My laugh. The way I sat. Even the way I threw a pitch on the cricket ground. Less hesitation. And it’s true, brother, after discovering my first, true guru—the right guru—I felt . . . light . . . ”

“Light?”

“Still do. You can’t forget that feeling. You can always return to it, sure—that first moment of union. Connection. The event only happens once in a lifetime, sure. I found this place nobody can take away from me. Sometimes, it feels like I’m writing lines of Light on the page.”

William admires that René doesn’t apologize for his hubris. Is confidence hubris? William thinks of a great dancer, grips the edge of his plastic chair. Where were René’s thoughts coming from? From what source do they originate? They just flowed out. Maybe something about that samurai film—the gauntness of Miyamoto Musashi—uncorked the bottle.

That first afternoon studying poetry with Miss Johnson, William didn’t know he was meeting his first true-true guru. That chorus on Keats’s Negative Capability. How much has changed. William shakes René’s hand and doesn’t know why—he feels so, deeply—their talk had drawn them closer, forever.

“But I’ve digressed,” René says, wincing like he stubbed his toe against the sofa, turning as red as a brown man can manage.

William sees a drip painting by Jackson Pollock color that blank movie screen.

“Your why . . . ” William insists, turning toward René, forcing himself not to inch closer to the edge of his seat.

“Ah,” René says, still smiling; he is whispering now. “This ‘why!’ Well, my brother, we ain’t better than nobody. My mamma told me that. Daddy. But we must acknowledge—by Grace or accident—we found something. Discovered something. Touch something. You certainly did. I read your poem in The Grecian Journal.”

“You did?” William asks, growing suddenly warm.

“That Oresteia! Man: your poem—as I read it—comes from this obsession with unraveling how a son can defend the murder of his father.”

William bites his lip.

“Go on,” William whispers.

“That St. Lucian fellow. Walcott?”

“Derek Walcott,” William says.

“Yes, Derek Walcott. You share his music, are clearly inspired by it,” René says.

William will soon fall out of his chair.

“Ay, don’t get too cocky, brother. You don’t wanna write one poem; you wanna write a career. Sometimes I’ll get stuck, you know? On some passage from an ancient epic—I’ll get anxious. Think back to my childhood. Ask: who am I? This Trini boy writing about great battles in India. The Mughals. I’d die in war.”

“We are about to go to war,” William says. “What do you do, René? When you get anxious?”

“Run, brother,” René says. “Go back home. Shower. Ice-cold shower. Work before my mind even gets the opportunity to chatter. Get out ahead of it all. The pain. Memory. Why I love Trinidad Barbell so much. Boy, this brain sure does chatter. Listen for that right whisper—from where? God? Telling me: Son, you can only do what you can, and that’s sufficient. Was running last September down Riverside Park, got to the barrier, slumped down, palms on my knees. Retched right there in that river—felt relieved. Space opened up—from where?—for a solid thought to arrive—from who? I knew I had to learn more about this Freedom Riding business, William. I just feel it—I know we have to go.”

Stephen Narain was raised in the Bahamas by Guyanese parents and moved to Miami at seventeen. A graduate of Harvard College and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he is the recipient of the John Thouron Prize at Cambridge University, the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowship for New Americans, the Small Axe Fiction Prize, the Alice Yard Prize for Art Writing, and the Bristol Short Story Prize. His fiction and essays have appeared in Small Axe: A Platform for Caribbean Criticism, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Wasafiri’s special issue on the afterlives of indentured labor. Before beginning his PhD at the University of Miami, Stephen spent over a decade teaching literature and writing at the University of Iowa, Valencia College in Orlando, and The Door: A Center of Alternatives, a youth advocacy center in Lower Manhattan.

Read more from the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing 2025 Finalists.