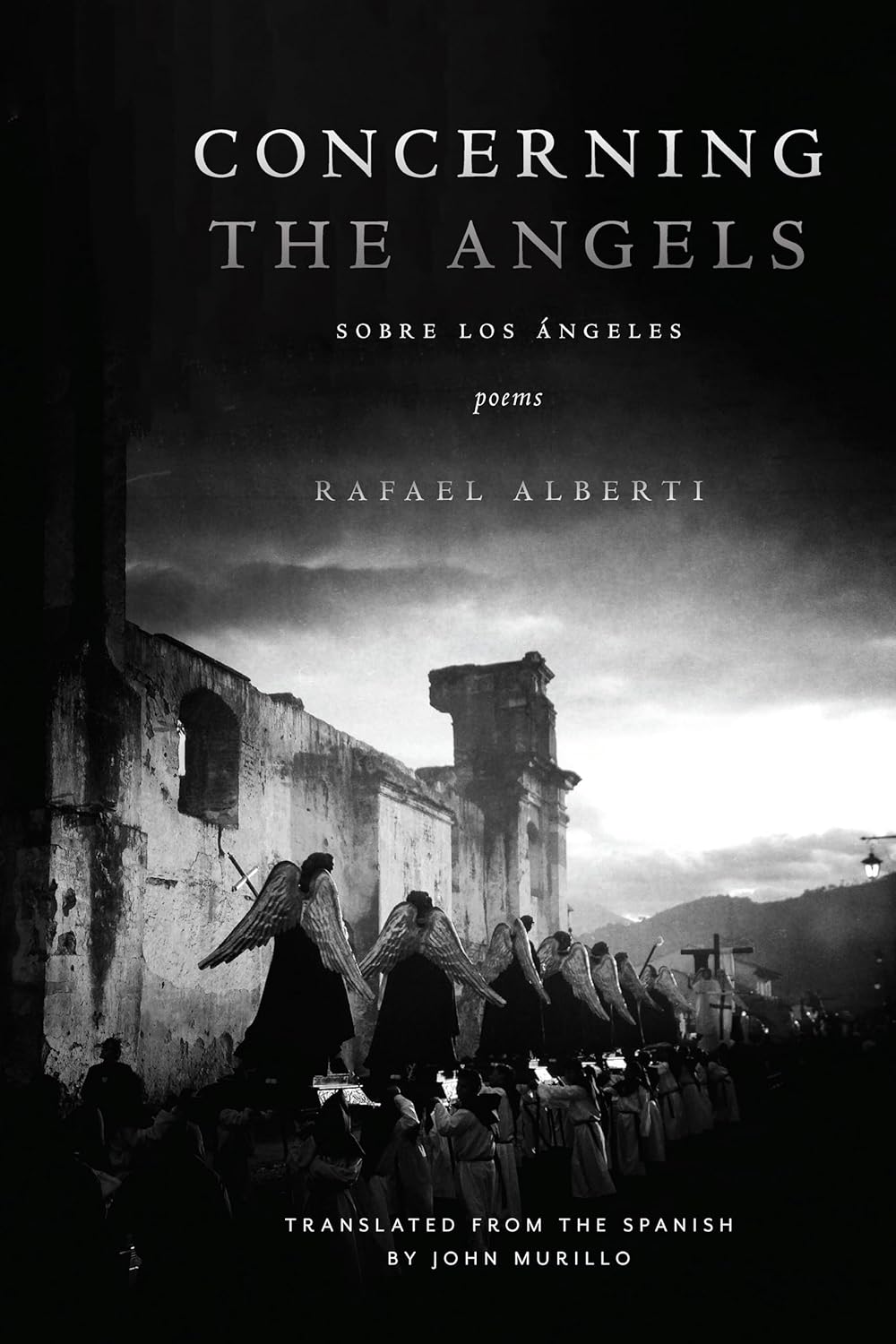

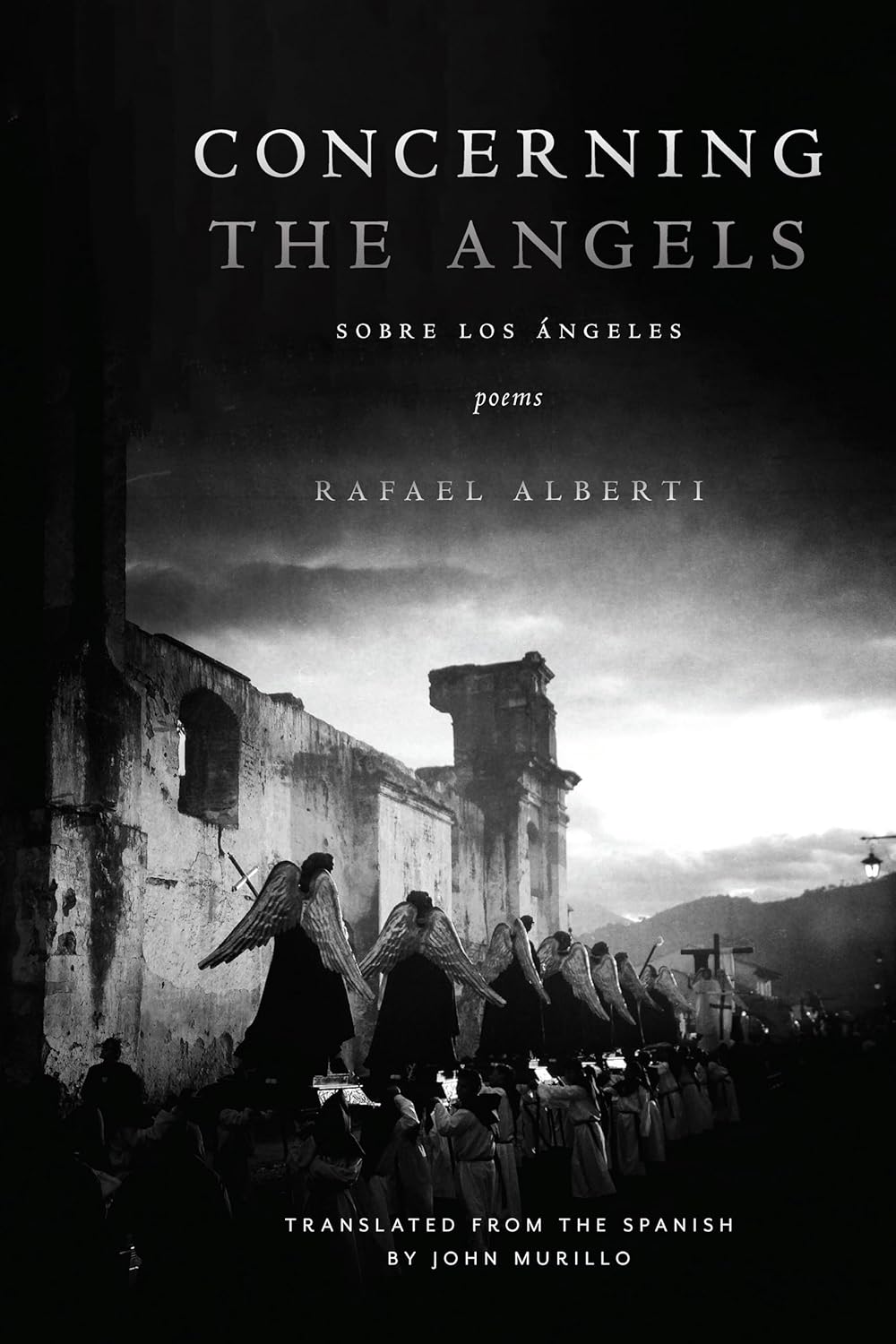

Poems by RAFAEL ALBERTI

Translated from the Spanish by JOHN MURILLO

From Rafael Alberti’s Concerning the Angels, forthcoming in March from Four Way Books.

Poems appear in both English and Spanish.

Table of Contents:

- Introduction by John Murillo

- LOS ÁNGELES VENGATIVOS (The Vengeful Angels)

- CAN DE LLAMAS (Hound of Flames)

- EL ÁNGEL TONTO (The Foolish Angel)

- EL ÁNGEL DEL MISTERIO (The Angel of Mystery)

- ASCENSIÓN (Ascension)

Translator’s Note

Begun just five years after T.S. Eliot published The Waste Land, and completed the year before Federico Garcia Lorca was to start on what would eventually become Poet in New York, Rafael Alberti’s Sobre los Angeles is a monument—albeit a severely neglected monument—of early twentieth-century literature. Like Eliot, who sought to capture something of the despair of post-war London, and Lorca, who, while traveling through parts of North America and the Caribbean, bore witness to the consequences of industry, both its worship and eventual collapse, Alberti penned a masterwork of social and psychic malaise as deserving as any of its place in the global canon. A masterwork which, though all but forgotten by English language readers of poetry, we might find especially relevant today given its treatment of themes and realities one fears recurring, if not chronic.

By the time Alberti published this collection, he was already a poet of stature in his native Spain. Born Rafael Alberti Merello, December 16, 1902, in the Puerto de Santa María region of Cádiz, he was, along with Lorca, Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí and several other notables, a member of a loose collective of artists and intellectuals that has come to be known as “The Generation of ’27.” (The name alludes to the date of their first official meeting, held on the tercentenary of the death of the poet Luis de Góngora. But as C.B. Morris points out in his brilliant study, A Generation of Spanish Poets, 1920-1936, it “magni[fies] the significance” of their connection to Góngora, and serves only as a shorthand reference for a group of friends of roughly the same age “who were never fused by a programme into a clearly defined school.”) His first collection, El Marinero en Tierra (1925), was selected for the National Literature Prize by a panel of judges that included novelist Gabriel Miró and poet Antonio Machado. He followed with other collections such as La Amante (1926) and Cal y Canto (1929), each widely acclaimed in its own right. With such early success, one imagines this might have been a time of great joy for the young Alberti.

But as productive as these years were for the poet, they found his country at a crossroads. Spain, though neutral in the first world war, was nonetheless adversely affected and left, years later, still reeling in its aftermath. A suffering economy. Strained infrastructure. Labor strikes and food riots. A long-lasting chasm between countrymen whose loyalties were split between the allied forces on the one side and the central powers on the other. Such instability made possible the juntas that would shape Spain for what must have felt then like the foreseeable future. By the time Alberti hit his stride as a poet, Spain was under the dictatorial rule of one Captain General Miguel Primo de Rivera, father of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, who, in turn, would one day father the fascist Falange Española. The country Alberti knew and loved as a child had become a foreign and hostile land. Though he claims not to have known much about politics at the time, and would only come to understand much later such words as “Republic, Fascism, liberty,” he could definitely feel the landscape changing. “I had lost a paradise,” Alberti writes in his memoir, The Lost Grove, “the Eden of those early years: my happy, bright and carefree youth.”

This was also a period of great personal suffering for the poet. In addition to the world’s woes and his own declining health, other sources of discontent included “[a]n impossible love that had been bruised and betrayed during moments of confident surrender; the most rabid feelings of jealousy which would not let me sleep and caused me to coldly contemplate a calculated crime during the long sleepless nights; the sad shadow of a friend who had committed suicide… Unconfessed envy and hate… [E]mpty pockets that could not even warm my hands… My family[,] silent or indifferent in the presence of this terrible struggle that was reflected on my face and in my very being… [M]y displeasure with my earlier work… all this and more.

“What,” Alberti asks, “was I to do? How was I to speak or shout or give form to that web of emotions in which I was caught? How could I stand up straight once again and extricate myself from those catastrophic depths into which I had sunk[?]” The only solution for Alberti, as for any poet, was to write his way through. Initially, without any consideration of form or convention, almost automatically, and in feverish fits. Some nights, he would rise from bed to scrawl, in the dark, lines he could barely decipher come morning. Within the span of two years, Alberti would not only have given vent to his sorrows, he would also have written what many consider his magnum opus.

Sobre los Angeles was published in early 1929 to mixed critical reception. For the most part, critics praised Alberti’s new direction. One such critic was José Martinez Ruiz, for whom the collection “signal[ed] [Alberti’s] having reached ‘the highest peak of lyric poetry.’” Still, there were one or two others, like poet Juan Ramón Jimenez, a personal hero and early champion of Alberti, who disparaged the latter’s “disjointed prattling,” finding it too radical a departure from his previous work. (Both Morris and Alberti, it may be interesting to note, surmise that Jimenez’ critique had less to do with the book itself and more to do with a personal qualm, with his having felt abandoned by a generation of younger poets who had previously considered him a guiding force but were now blazing their own trails.) In toto, however, the years have been kind to Alberti, with the vast majority of critics and scholars in the field (albeit outside the continental United States) recognizing the collection’s merit.

While it is true that these poems mark a stylistic, thematic, and tonal shift, Alberti’s rigor, his attention to detail, remain constant. His choices, deliberate. When discussing, for instance, some of the structural considerations in the manuscript, Alberti remarked that “the short, controlled and concentrated verse line I had been writing gradually became longer and more in keeping with the movement of my imagination in those days.” If these were poems drafted in the dark, they were also poems thought through, worked for, and revised in the full light of day. As concerns the cryptic images, the often opaque associations, in many of the poems—which were some of the key annoyances among Alberti’s detractors—we would do well to remember our Lorca who, in an unrelated essay, reminds us that there exist poems “that respond to a purely poetic logic and follow the constructs of emotion and poetic architecture;” our Lorca who, many scholars, such as his biographer Ian Gibson, believe, carried with him on his voyage across the Atlantic a copy of Sobre los Angeles.

Speaking of Lorca, it’s worth mentioning at this point that until his assassination in August of 1936, he and Alberti were often mentioned in tandem, as the two shining lights of “The Silver Age” of Spanish poetry. Friends and rivals, they shared not only a common appreciation of Andalusian folk art, respect for classical verse forms, and, paradoxically, a penchant for innovation, but nearly parallel literary careers—each publishing roughly the same number of books within the same timespan to, more or less, the same acclaim. By many accounts, Alberti was even considered the superior poet, the more versatile technician, equal to Lorca in imagination. Whereas Lorca died young, Alberti would live to age 96, write well over thirty books of verse and prose, and become, like Lorca, one of Spain’s most celebrated poets. His honors include, in addition to the 1924-1925 National Prize for Literature, the International Lenin Peace Prize, the prestigious Premio Cervantes, and the America Award for lifetime achievement, whose other honorees include Aimé Cesaire, José Saramago, Eudora Welty, and Mario Vargas Llosa. And yet, while any decent bookstore in the U.S. will carry a variety of Lorca translations—In Search of Duende, Poet in New York, his selected and collected poems, his plays—Alberti has fallen into relative obscurity.

In 2022, the University of California Press reissued Ben Belitt’s selected Alberti as part of their “Voices Revived” series. Prior to this, Belitt’s collection, originally published in 1966, had been unavailable for years. Or, rather, available only through second-hand booksellers and websites. The same is true of Mark Strand’s 1982 selection of translated Alberti titled The Owl’s Insomnia. In 2001, City Lights published Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno’s translation of Sobre los Angeles but that too has gone out-of-print. While it is beyond the scope of this introduction to speculate upon the reasons behind this diminished interest, perhaps it is not too much to lament it, to recognize it as a tremendous loss for us all.

This volume is in no way intended to serve as The Definitive Alberti, but rather as a humble attempt to share with a new generation of readers an important, maybe indispensable, voice.

—John Murillo

Brooklyn, March 2024

Portrait of Murillo.

LOS ÁNGELES VENGATIVOS

No, no te conocieron

las almas conocidas.

Sí la mía.

¿Quién eres tú, dinos, que no te recordamos

ni de la tierra ni del cielo?

Tu sombra, dinos, ¿de qué espacio?

¿Qué luz la prolongó, habla,

hasta nuestro reinado?

¿De dónde vienes, dinos,

sombra sin palabras,

que no te recordamos?

¿Quién te manda?

Si relámpago fuiste en algún sueño,

relámpagos se olvidan, apagados.

Y por desconocida,

las almas conocidas te mataron.

No la mía.

THE VENGEFUL ANGELS

No, the known souls

did not know you.

Mine did.

Who are you, tell us, who do not remember you

from earth or from heaven?

Your shadow—tell us—is from what space?

What light, say it, has reached

into our realm?

Where do you come from, tell us,

shadow without words,

that we don’t remember you?

Who sent you?

If you were lightning in a dream,

lightning is forgotten, doused.

And for being unknown,

the known souls murdered you.

Not mine.

CAN DE LLAMAS

Sur.

Campo metálico, seco.

Plano, sin alma, mi cuerpo.

Centro.

Grande, tapándolo todo,

la sombra fija del perro.

Norte.

Espiral sola mi alma,

jaula buscando a su sueño.

¡Salta sobre los dos! ¡Hiérelos!

¡Sombra del can, fija, salta!

¡Únelos, sombra del perro!

Riegan los aires aullidos

dentados de agudos fuegos.

¡Norte!

Se agiganta el viento norte…

Y huye el alma.

¡Sur!

Se agiganta el viento sur…

Y huye el cuerpo.

¡Centro!

Y huye, centro,

candente, intensa, infinita,

la sombra inmóvil del perro.

Su sombra fija.

Campo metálico, seco.

Sin nadie.

Seco.

HOUND OF FLAMES

South.

Metallic field, barren.

Plain, soulless, my body.

Center.

Vast, blanketing everything,

the petrified shadow of the dog.

North.

Spiral solo my soul,

jailcell in search of its dream.

Leap over both! Hurt them!

Shadow of the hound, petrified, leap!

Unite them, dog shadow!

Jagged howls of high flames

saturate the air.

North!

The north wind swells…

and the soul escapes.

South!

The south wind swells…

and the body escapes.

Center!

And the center escapes,

incandescent, intense, infinite,

the static shadow of the dog.

His petrified shadow.

Metallic field, barren.

Desolate.

Bone-dry.

EL ÁNGEL TONTO

Ese ángel,

ése que niega el limbo de su fotografía

y hace pájaro muerto

su mano.

Ese ángel que teme que le pidan las alas,

que le besen el pico,

seriamente,

sin contrato.

Si es del cielo y tan tonto,

¿por qué en la tierra? Dime.

Decidme.

No en las calles, en todo,

indiferente, necio,

me lo encuentro.

¡El ángel tonto!

¡Si será de la tierra!

—Sí, de la tierra solo.

THE FOOLISH ANGEL

That angel,

that one who denies the limbo of his photograph

and makes a dead bird

of his hands.

That angel who fears they will ask for his wings,

that they will kiss his beak,

seriously,

without a contract.

If he is from heaven and so foolish,

why is he on earth? Tell me.

Tell me.

Not in the streets, but everywhere,

indifferent, foolish,

I find him.

The foolish angel!

He will be of the earth!

Yes, from the earth alone.

EL ÁNGEL DEL MISTERIO

Un sueño sin faroles y una humedad de olvidos,

pisados por un nombre y una sombra.

No sé si por un nombre o muchos nombres,

si por una sombra o muchas sombras.

Reveládmelo.

Sé que habitan los pozos frías voces,

que son de un solo cuerpo o muchos cuerpos,

de un alma sola o muchas almas.

No sé.

Decídmelo.

Que un caballo sin nadie va estampando

a su amazona antigua por los muros.

Que en las almenas grita, muerto, alguien

que you toqué, dormido, en un espejo,

que yo, mudo, le dije…

No sé.

Explicádmelo.

THE ANGEL OF MYSTERY

A dream without lanterns and a dank forgetfulness,

trampled by a name and a shadow.

I don’t know whether by one name or many names,

whether by one shadow or many shadows.

Reveal it to me.

I know that cold voices inhabit the wells,

that they are of a single body or of many bodies,

of a single soul or of many souls.

I don’t know.

Tell me.

That a horse with no rider goes stamping

its old equestrian to the walls.

That on the parapet hollers, dead, someone

that I touched, asleep, in a mirror,

that I, mute, said to him…

I don’t know.

Make it plain for me.

ASCENSIÓN

Azotando, hiriendo las paredes, las humedades,

se oyeron silbar cuerdas,

alargadas preguntas entre los musgos y la oscuridad colgante.

Se oyeron.

Las oíste.

Garfios mudos buceaban

el silencio estirado del agua, buscándote.

Tumba rota,

el silencio estirado del agua.

Y cuatro boquetes, buscándote.

Ecos de alma hundida en un sueño moribundo,

de alma que ya no tiene que perder tierras ni mares,

cuatro ecos, arriba, escapándose.

A la luz,

a los cielos,

a los aires.

ASCENSION

Whipping, wounding the walls, wounding the dank,

ropes were heard whistling,

stretching questions between moss and the hanging dark.

They were heard.

You heard them.

Mute hooks dredged

the stretched silence of the blue, in search of you.

Broken sepulcher,

the stretched silence of the blue.

And four chasms, in search of you.

Echoes of a soul sunk in a dying dream,

of a soul that no longer has lands or seas to lose,

four echoes, above, escaping.

To the light,

to the skies,

to the air.

John Murillo is the author of the poetry collections Up Jump the Boogie, finalist for both the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the Pen Open Book Award, and Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry, winner of the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award and the Poetry Society of Virginia’s North American Book Award, and finalist for the PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry, the Hurston-Wright Legacy Award and the NAACP Image Award. His other honors include two Pushcart Prizes and the Four Quartets Prize from the T.S. Eliot Foundation and the Poetry Society of America. He is a professor of English and teaches in the MFA program at Hunter College.