Text by FRANCISCO FONT-ACEVEDO

Images by RAFAEL TRELLES

Santurce, originalmente llamado Cangrejos, fue municipio desde el siglo XVIII, aunque luego fuera anexado como barrio de San Juan. Fue también el primer pueblo fundado por negros en Puerto Rico en 1773, cien años antes de la abolición de la esclavitud en el país. A partir de la construcción del trolley (primero a vapor en el último cuarto del siglo XIX, luego eléctrico a partir del 1901), se cambió el nombre de San Mateo de Cangrejos al de Santurce, en homenaje a Pablo Ubarri, Conde de Santurzi, encargado de la instalación del tren. Durante el siglo XX, en especial durante la modernización del país a partir de los años 40, Santurce se convirtió en el centro económico y cultural del país. Llegó a tener una población de 195,000 personas en 1950. Luego del proceso de suburbanización del país y la construcción de los centros comerciales a partir de finales de los años 60, la importancia de Santurce decayó notablemente. En la actualidad su población ronda los 82,000. Aun así, sigue siendo el barrio más poblado del país.

Los textos que siguen están narrados por Santurce/Cangrejos mismo. Las imágenes son de los murales tal como se reprodujeron e instalaron por todo el barrio. En todos los murales hay una imagen, un texto, el título del libro, un mapa y unas instrucciones para el peatón.

Para más información puedes ver nuestra página web: www.santurceunlibromural.com.

Although it was later annexed as a neighborhood of San Juan, Santurce—originally called Cangrejos—has been a municipality since the eighteenth century. It was also the first town founded by blacks in Puerto Rico, in 1773, one hundred years before the abolition of slavery in the country. Since the construction of the trolley (first the steam model in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, then the electric one in 1901), San Mateo de Cangrejos was renamed Santurce in homage to Pablo Ubarri, Count of Santurtzi, responsible for building the commuter railroad system. Throughout the twentieth century, particularly during the modernization of the country which began in the 1940s, Santurce became the island’s economic and cultural center, with a population of 195,000 people in 1950. After the suburbanization of the country and the construction of malls at the end of the 1960s, Santurce’s importance declined significantly. Its population now stands at approximately 82,000. Even so, it remains Puerto Rico’s most populous district.

The texts that follow are narrated by Santurce/Cangrejos itself. The images are of the murals just as they were reproduced and installed throughout the neighborhood. Each mural includes an image, a text, the title of the book, a map, and instructions for pedestrians.

For more information, visit our website: www.santurceunlibromural.com.

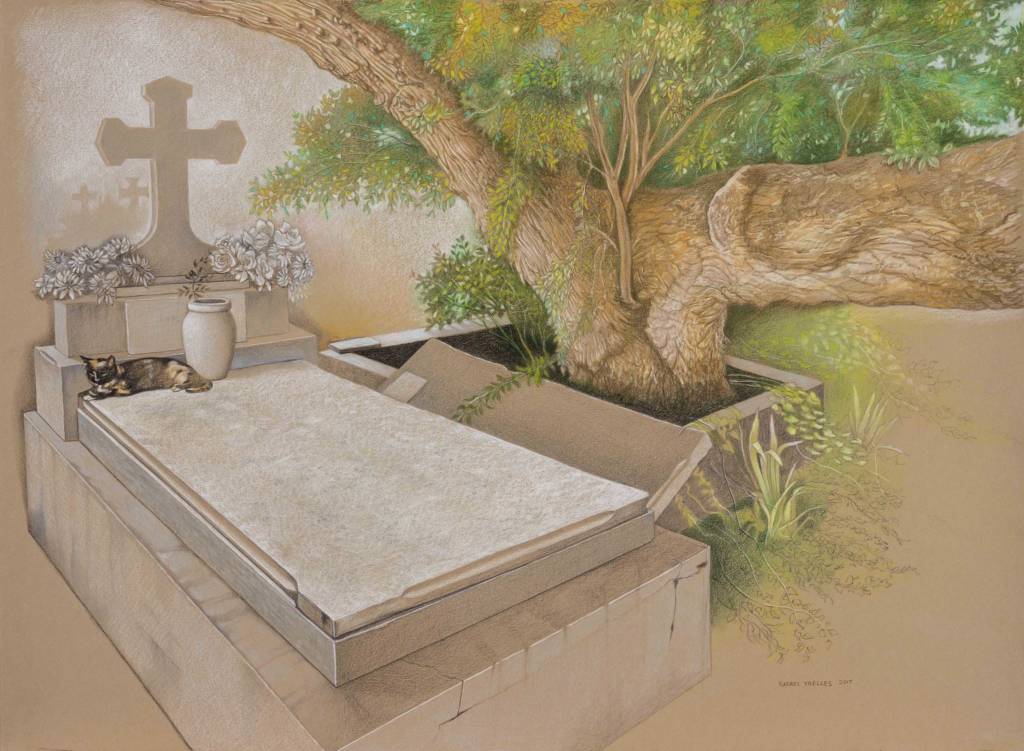

Villa Crucis

Al este —donde primero calienta el sol— hallarás el cementerio de Villa Palmeras. Allí moran mis muertos y se asientan mis dominios. Sepa que establecer un territorio es fundar un mundo, pero es el otro, soterrado, el que lo sustenta. Por esto mi primer fundamento fue El Muerto: el primero que hincó y abonó mis entrañas; ese que hizo brotar la ceiba que daría sombra a los descendientes; aquel cuya ausencia desató—en cuento y fantasma—la memoria colectiva. Visite mi villa crucis y vea su numerosa descendencia. Si va un 2 de noviembre escuchará a los más rumbosos tocando bembé.

Villa Crucis

To the east —where the sun first warms the earth— you’ll find Villa Palmeras Cemetery. There my dead dwell and my realms reside. You should know that settling a territory is like constructing a world, but it’s the other, the buried one, that sustains it. That’s why my first foundation was The Dead: the first to plunge down and fertilize my womb; the one that gave birth to the ceiba tree that would shade its heirs; the one whose absence sparked, in stories and ghosts, the collective memory. Visit my villa crucis and see its numerous descendants. If you go on November 2, you’ll hear the more rambunctious playing bembé.

El arcoíris

Entre el pudor y el desenfado se equilibraban mis amantes clandestinos. Al desenfado de interior (con música, licor y cuartos oscurecidos) le seguía el pudor obligado de la calle, un pulido trasiego de señas y sobrentendidos. Solo por la Ashford o las inmediaciones de la Laguna los más atrevidos sacaban a pasear el amor de la mano. A resguardo ha sido su amor pero cada vez menos, pues desde hace veintitantos años marchan por mis calles en reclamo y celebración de sus colores. Mía ya es su bandera de arcoíris y mis dominios, uno de sus baluartes.

The Rainbow

My clandestine lovers swayed between abandon and restraint. Indoor lack of inhibition (with music, liquor, and darkened rooms) would be followed by forced modesty on the street, a subtle exchange of signs and mutual understandings. Only on Ashford Avenue and the backstreets of Condado Lagoon did the most daring hold love by the hand. Their love took place in the shadows, but less so over time, because for twenty-odd years they have been marching down my streets in protest and in celebration of their colors. Mine is their rainbow flag, and my domains one of their bastions.

La resaca

¿Andas de farra, jangueo? ¿Otro viernes social? Sean todos bienvenidos a mis calles, a mi Placita del Mercado; no faltarán alternativas para el desquite y el goce multitudinario. Nombra tu deseo y te aseguro una ilusión satisfactoria. Anda y pruébame; hace siglos que me doy a los excesos sin chistar. Cinco colinas, cinco caderas tengo para tu frenesí. Aprovecha y disfrútame, mi hospitalidad conoce pocos límites. Pero vete, eso sí, antes de que salga el sol. A no ser que quieras ver mis vagabundos, mi lepra arquitectónica. Compartir conmigo la resaca cotidiana.

The Hangover

Partying? Hanging out? Another night on the town? Welcome to my streets, my Placita; opportunities abound to loosen up and have a blast. Name your desire and I guarantee you a satisfying illusion. Come try me; for centuries I’ve been giving in to excess without hesitation. I have five hills, five hips to quell your frenzy. Enjoy, take advantage of me—my hospitality knows no bounds. But leave before the sun comes up. Unless you want to see my homeless, my architectural decay, and share with me the daily hangover.

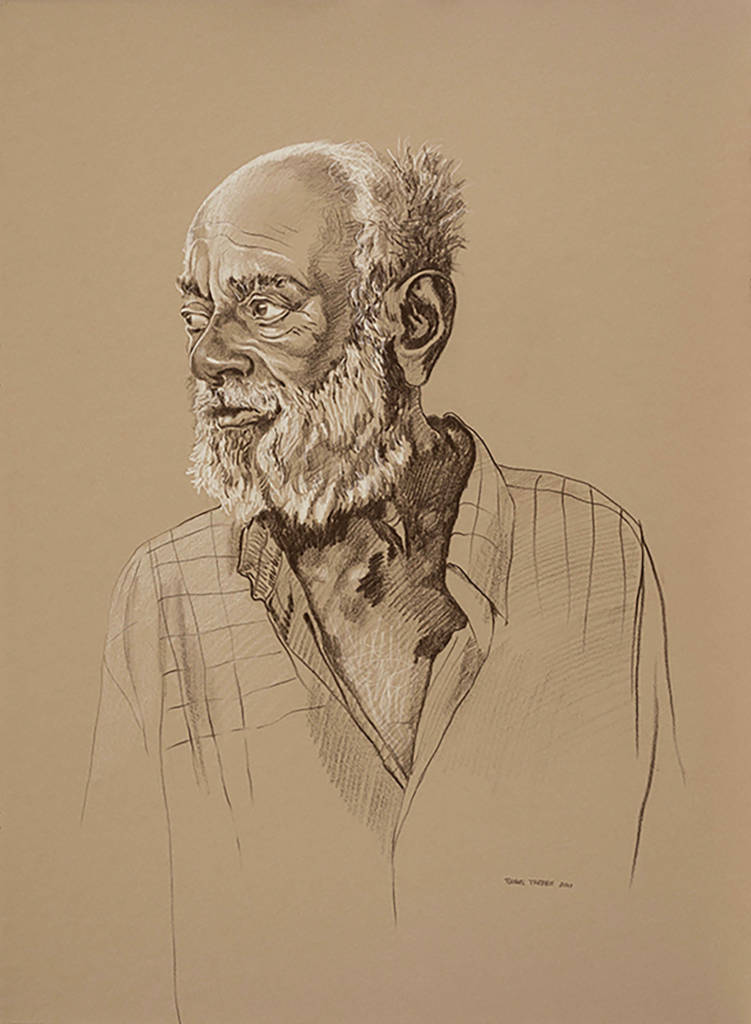

El lazareno

Los confunden con mis adictos porque unos y otros extienden hedor y mugre desde la Placita Barceló hasta los comercios de Miramar. Pero no; son, clase aparte, mis heraldos de la locura. Habitantes del inframundo, uno pregona obscenidades a carcajadas, otro duerme junto a una prótesis, alguna se desvive por pasear perros en un carrito de supermercado. Entre estos se distingue un viejo negro con bastón, ropas raídas y descalzo que, silencioso, fuma cigarros. Cada domingo, nada más sentarse en la Placita del Mercado, los asiduos lo colman de comida y café. El justo agasajo al más místico de mis lázaros.

The Lazarene

They’re often confused with my addicts, because both spread stench and grime from Placita Barceló to the businesses in Miramar. But no, they are a class apart, my heralds of madness. Inhabitants of a netherworld, one cackles and shouts obscenities, another sleeps alongside a prosthesis, and yet another goes out of her way to walk dogs in a shopping cart. Among them stands out an old black man with a cane and frayed clothes, barefoot and silent, smoking cigars. Every Sunday, as soon as he sits at La Placita, the regulars shower him with food and coffee. A fair reception for my most mystical Lazarus.

Los regresados

Hartos del mall y la suburbia regresarán a una imaginaria ciudadela. Con barbas toscas él, tatuada y sin maquillaje ella, ambos —con botas— volverán sobre los pasos de antepasados desconocidos. A pie y en bicicleta recorrerán mis calles, pintarán murales, en inglés y español me profesarán una devoción casi publicitaria. Ensayarán la creación artesanal: de tres paredes harán un cine, de un vagón un restaurante, de telas y cachivaches una tienda de antigüedades. Comerán y fumarán verde, y por un tiempo se embelesarán ante mis ruinas. Luego, como tantos antes, partirán en busca del próximo paraíso.

The Returned

Fed up with the mall and suburbia, they will return to an imaginary citadel. Him with a coarse beard and her tattooed and makeupless, both—in boots—will retrace the steps of unknown ancestors. By foot and bicycle, they will roam my streets, paint murals, and advertise their devotion to me in English and Spanish. They will practice arts and crafts: out of three walls they’ll make a theater, out of a trailer a restaurant, out of knickknacks an antique shop. They will drink and smoke green and, for a while, be mesmerized by my ruins. Then, like so many before them, they will depart in search of the next paradise.

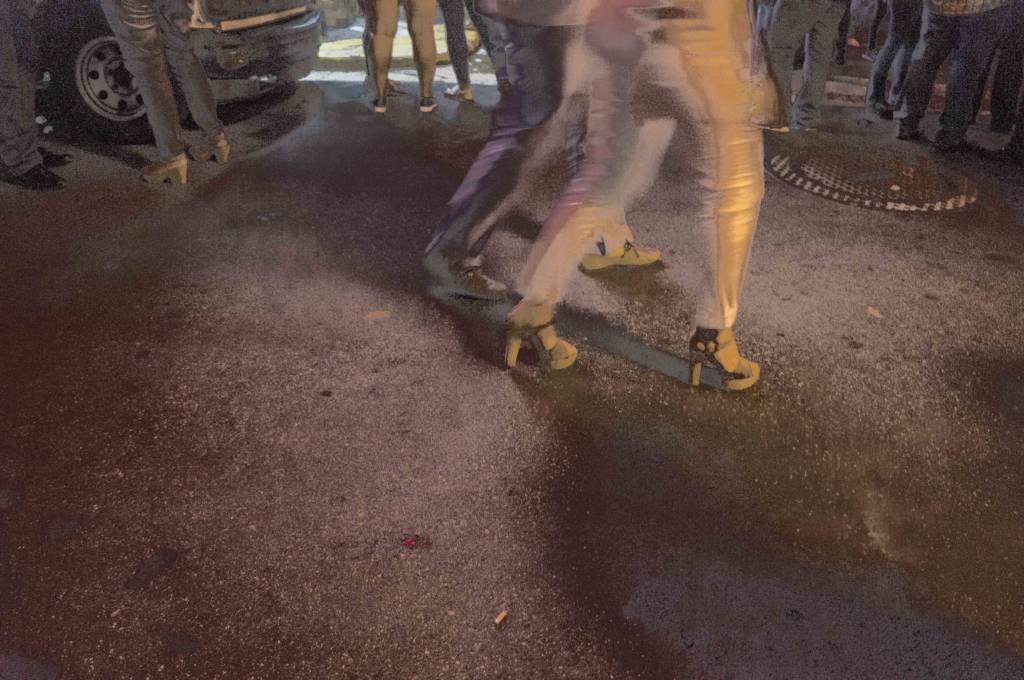

La jauría roja

Casas de lenocinio hubo —algunas de leyenda negra— en mis dominios; barras, pubs y discotecas complementaban la oferta para el desahogo de calenturas. Pero la vida alegre más descarnada siempre fue en tacos y a la intemperie. Primero ellas, luego también ellos y ell@s atraían con brillo la presa a la oscuridad de mis callejones. En breve la jauría—con los colmillos en los bolsillos—iba llegando a comprar escenas o actos de lujuria maquillada. Hubo transacciones que terminaron en sangre. Digo sangre por no decir muertos. Digo hubo por no decir ay.

The Red Hounds

There were brothels—some of black legend—in my domains; bars, pubs, and discos complemented their offer to satisfy hidden desires. But the starkest reality of the life of easy virtue was always in heels and out in the open. First women, then men, lured their prey with sequins into the darkness of my alleys. Soon the hounds—baring their fangs—came to buy scenes of made-up lust. There were transactions that ended in blood: I say were so as not to say are; I say blood so as not to say death.

La suerte

No es ni será la última crisis. Peatones y vehículos, arribistas y miserables, siempre han coexistido en mí. Pocos suben, muchos caen; se cierra un ciclo y se abre otro. No hay buena fortuna que no se gaste, ni infortunio que no recese. Puede que grites de desesperación o de júbilo, o puede que, como yo, dividas por parcelas tu buena y mala suerte. Lepra o brillo, mudo el carapacho de nuevo y cambio mis letreros. Como tú con tu piel y tu dentadura. A veces somos paisajes de polvo, a veces de aguacero.

Wheel of Fortune

This is not and will not be the last crisis. Pedestrians and vehicles, the opportunists and the miserable, have always coexisted in me. Few rise, many fall; one cycle ends, and another begins. There’s no good fortune that lasts, nor wave of misfortune that doesn’t ebb. You may cry out in despair or cry for joy, or perhaps, like me, parcel out your good and bad luck. Leprosy or luster, I shed my skin again and change my signposts. Just as you would your hair and teeth. Sometimes we’re a dusty wasteland, others a lush green grove.

Translated by Joan M. Pabón Maxán

Francisco Font-Acevedo is a Puerto Rican writer born in Chicago, Illinois. He is the author of La Troupe Samsonite, La Belleza Bruta, and Caleidoscopio. Font-Acevedo was a literary critic for Radio Universidad and Plural, a literary and cultural journal. He has worked as a language instructor, translator, interpreter, freelance editor, and legal proofreader. He currently lives in Philadelphia.

Rafael Trelles is a Puerto Rican painter and visual artist whose prolific work covers sculpture, installations, performances, urban interventions, digital photography, and other experimental media. Trelles has participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Puerto Rico, the United States, Europe, and Latin America. His works are housed in various art collections, such as those of Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico, Museo de Arte de Ponce, and Ramapo College in New Jersey, among others. He has received awards from the Puerto Rico Chapter of the International Association of Art Critics for his exhibitions in 1991, 2004, and 2007, as well as awards from Revista Sin Nombre, Fondo Nacional para el Financiamiento del Quehacer Cultural de Puerto Rico, Fundación Ricardo Alegría’s Medalla de la Cultura (Medal of Culture), and the Innovation and Change in Higher Education Award from the Center for Academic Excellence of the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras.

Joan M. Pabón Maxán is a Puerto Rican translator, editor, and copywriter. A product of the island’s public education system and a long-term rural resident, she has strived to achieve academic and professional success in a competitive, at times inhospitable job market. Pabón, an avid reader and amateur fountain pen collector, currently works as a managing editor for a consumer review website and is a founding member of the translators’ collective TraduCoop, soon to become the first translators’ cooperative of Puerto Rico. She now lives near San Juan’s Golden Mile with her little sister and a lizard-hunting foster cat named Koko.