By ERICA DAWSON

The counselors told us to fucking go

to bed; but, earlier they’d taught us one

more Christian song—

It only takes a spark

to get a fire going—

By ERICA DAWSON

The counselors told us to fucking go

to bed; but, earlier they’d taught us one

more Christian song—

It only takes a spark

to get a fire going—

By W. RALPH EUBANKS

All thinking Southerners, at some point, find their minds at war with their hearts, a battle that often ends with the heart claiming victory. It is this triumph of the heart that landed me, a black expatriate Mississippian, back in my home state again. Yet returning to Mississippi after nearly forty years, albeit temporarily, as a visiting professor, has left me torn somewhere between acceptance and separateness. In some ways, the longer I am in the South, the less I try to maintain my distance from the place.

Translated by OSTAP KIN

A good day is a day

without bad news.

Sometimes everything turns out fine—

no news,

no fiction.

Three thousand steps to the supermarket

frozen chickens

like dead stars

gleam after death.

All you need is

mineral water,

I only

need my mineral water.

Execs, like

frozen chickens,

are hatching

the eggs

of profit

in the twilight.

Three thousand steps back.

All I need to do is hold on

to my mineral water,

to hold on to

the countdown:

thirty-two days without alcohol

thirty-three days without alcohol

thirty-four days without alcohol.

Birds perch on each of my shoulders,

and the one on the left keeps repeating:

thirty-two days without alcohol

thirty-three days without alcohol

thirty-four days without alcohol.

And the one on the right responds:

twenty-eight days till a bender

twenty-seven days till a bender

twenty-six days till a bender.

And the one on the left is drinking the blood of Christ

from a silver chalice.

And the one on the right—the simpler one—

is drinking some crap,

some diet coke.

On top of that

they’re both drinking

on my tab.

Serhiy Zhadan, Ukrainian poet, fiction writer, essayist, and translator, was born in the Luhansk region in 1974 and has published over a dozen books. In 2014 he received the Ukrainian BBC’s Book of the Decade Award; he won the Ukrainian BBC’s Book of the Year Award in 2006 and in 2010. He’s the recipient of the Hubert Burda Prize for Young Poets (Austria, 2006) and the Jan Michalski Prize for Literature (Switzerland, 2014).

Ostap Kin has published work in St. Petersburg Review and Krytyka Magazine. He lives in New York City.

By PETER SCHMITT

It was a little blue purse she had asked for,

my mother, age four, when her father called

from the Mayo Clinic. With a silver chain—

and he had somehow found one in a pawnshop

Giyorgis Balthus: 1321-1400

1.

We surged in the moon-darkened

room, between counter-actions,

naked, our spectres clocking

the grey-scale before morning,

By ELVIS BEGO

The first time I came upon Raley was in a volume of Edith Wharton’s correspondence—a short, scabrous note he wrote from Venice in the winter of 1908. When I later read his Drowned City—one of those belated NYRB Classics that seem to appear out of a hidden crack in the library of Babel—I found its rooftop phantasmagoria irresistible. Tales of an unnamed city’s last population of gnarled maniacs, scheming widows, foolish valentines, old men whose eyes are black with mascara, boatmen mooring their vessels to weathervanes, women who sell their kisses for a dry bed. The city is half-sunk in its dream and no news of the world across the spent sea. “An imagination as awkward and prophetic as Kafka’s,” says the blurb, predictably. Nobody knew about the book for a hundred years. It was privately printed in Venice in 1899—only a trunkful of copies—and remained obscure till Edward Kingsley, the Anglo-Italian philanthropist-slash-Luddite, found it in a library in Burano. James Wood’s piece in the New Republic, although not without censure (“Raley’s iambic murmur too often apes the Jacobeans … but the wry vision is his own. His world is peopled by blind self-unravelers, and we are their stunned eavesdroppers”), sent me to the bookshop, and I tore through the two hundred perfect pages in a sitting.

By EMILY CHAMMAH

I wouldn’t say that Omar is my best friend, because I like to think we are closer than that, that there is something bringing us together more than any friendship could. While it is true that he is my cousin, I never feel as connected to the others—to Muhammad or Nour or Ahmed or Anais—or even to my older sister, Sousan. They don’t know, for example, that I prefer to drink my orange juice without sugar, that I’d rather eat falafels straight out of a paper cone than smashed inside a pocket of bread.

By VALERIE DUFF

Iron mallet, shield of glass. Our

genesis a crucible of gas

and condensation shot straight through the aorta

By JENNIFER ACKER

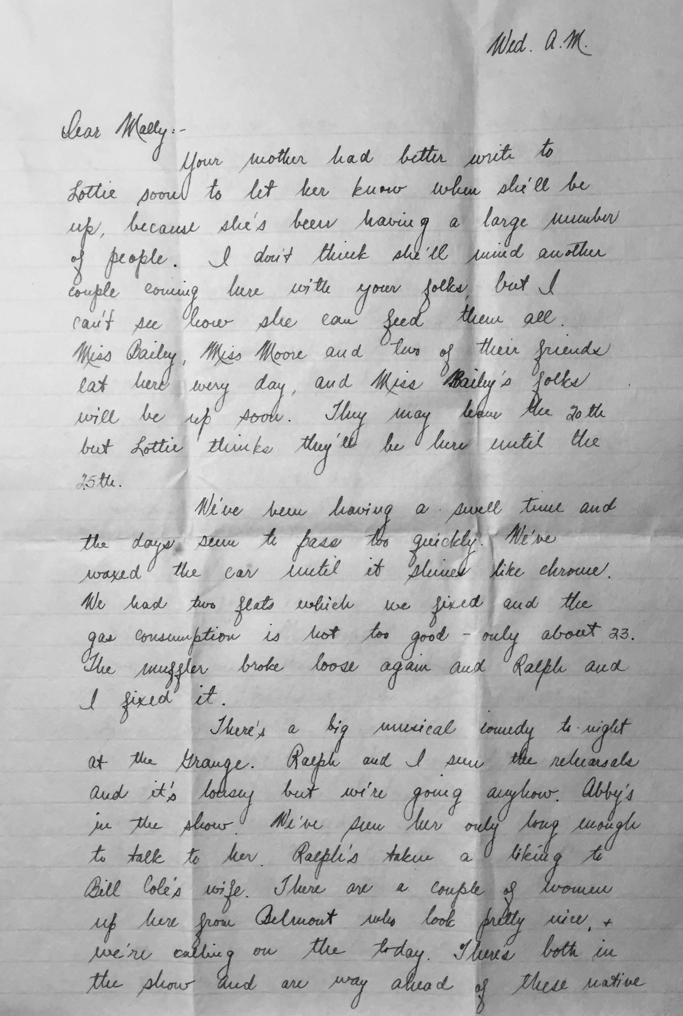

Mostly, Les gossips and writes about girls. One’s “a real peach” and another “darn nice.” Poor Esther has legs like parentheses—she “must have been born with a barrel between her legs.” Then there’s Mildred, who’s darn good-looking but too biting: “Sarcastic is no word. That’s complimenting her.” Les gets a little revenge when he sees her at a dance with “an awful dopey looking hobo.” He has a good time, even though “nearly every girl there was a pot.”

Mostly, Les gossips and writes about girls. One’s “a real peach” and another “darn nice.” Poor Esther has legs like parentheses—she “must have been born with a barrel between her legs.” Then there’s Mildred, who’s darn good-looking but too biting: “Sarcastic is no word. That’s complimenting her.” Les gets a little revenge when he sees her at a dance with “an awful dopey looking hobo.” He has a good time, even though “nearly every girl there was a pot.”

By CLARE BEAMS

The church ladies were having coffee in the living room of the Baker house when Martin Williams delivered his parachute to Lily Baker, his bride. Only some of the church ladies could really have been there, but in retellings they all claimed seats. They allowed one another this. A natural desire, to be part of the story.