By DAVID LEHMAN

Imagine the money the Keats estate would have made

if they could have copyrighted “negative capability”

and charged permission fees for its use, nearly as pricey

By DAVID LEHMAN

Imagine the money the Keats estate would have made

if they could have copyrighted “negative capability”

and charged permission fees for its use, nearly as pricey

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

The long New England winter is finally thawing, and here at The Common, we’re gearing up to launch our newest print issue! Issue 29 is full of poetry and prose by both familiar and new TC contributors, and a colorful, multimedia portfolio from Amman, Jordan. To tide you over, Issue 29 contributors DAVID LEHMAN and NATHANIEL PERRY share some of their recent inspirations, and ABBIE KIEFER recommends a poetry collection full of the spirit of spring.

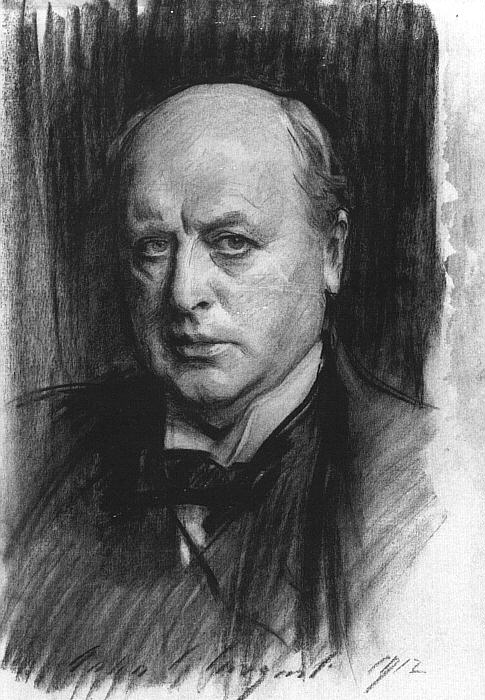

Henry James’ short works; recommended by Issue 29 contributor David Lehman

I’ve been reading or rereading Henry James’s stories about writers and artists: “The Real Thing,” “The Lesson the Master,” “The Death of the Lion,” “The Tree of Knowledge,” “The Figure in the Carpet,” “The Aspern Papers,” et al. His sentences are labyrinthine, and you soon realize how little happens in a story; the ratio of verbiage to action is as high as the price-earnings ratio of a high-flying semiconductor firm. Yet we keep reading, not only for the syntactical journey but for the author’s subtle understanding of the artist’s psyche—and the thousand natural and artificial shocks that flesh and brain are heir to.

New poems by our contributors DAVID LEHMAN, MATT DONOVAN, JULIA KOLCHINSKY DASBACH, and GRAY DAVIDSON CARROLL

Table of Contents:

By DAVID LEHMAN

The month, shortest of the year, least popular, ends,

and on the radio there’s “Midnight Sun,” a concept

worthy of a Ramos Gin Fizz, if you have the ingredients,

April Is Poetry Month: New Poems By Our Contributors

MARK ANTHONY CAYANAN, DAVID LEHMAN, and YULIYA MUSAKOVSKA (translated by the author and OLENA JENNINGS)

Table of Contents:

Mark Anthony Cayanan

—Ecstasy Facsimile (These days I ask god…)

David Lehman

—The Remedy

—A Postcard from the Future

—Last Day in the City

Yuliya Musakovska (translated by the author and Olena Jennings)

—Angel of Maydan

—The Sorceress’ Oath

New work from our contributors: ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA, DAVID LEHMAN, and MATT DONOVAN.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra | “The Walk”

David Lehman | “Just a Couple of Mugs”

Matt Donovan | “Portrait of America as a Philadelphia Derringer Abraham Lincoln Assassination Box Set Replica”

The Walk

By Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

In a tree hollow like a cave mouth,

in which you and your partner

selfied yourselves, is a trash bag

oozing trash juice.

Please join us in welcoming back contributor DAVID LEHMAN. This is the title poem of his new collection, The Morning Line.

The Morning Line

— May 22, 2020

1.

You can pick horses on the basis of their names

and gloat when Justify wins racing’s Triple Crown

or when, in 1975, crowd favorite Ruffian, “queen

of the century,” goes undefeated until she breaks down

in a match race with Derby winner Foolish Pleasure.

Who could root against Ruffian?

Did patriotic Englishmen cheer

when Sir Winston won the Belmont last year?

I rejoiced when Monarchos, a ten to one bet, became

the second horse ever to break the two-minute mark

at the Kentucky Derby. Why did I pick it? I liked the name.

Those two minutes in May 2001 and the giddy hours after

now seem a little like a garden party in England in July 1914

as the nineteenth century approached the finish line

and collapsed.

Today you might buy 50 shares of Qualcom at 78.11,

or 500 shares of Sirius at 5.15,

because you like the sound of their names,

and you may make these trades even without knowing

a thing about what the companies produce or do.

As luck would have it, under current market conditions,

a portfolio consisting of these two stocks plus Alphabet,

Amazon, and Apple would satisfy our poetry criterion

and stand a decent chance of outperforming the market,

as would a portfolio consisting of attractive stock symbols

like ACES, CAT, KO, NICE, QQQ, SPY, TAN, and TOKE.

“Under current market conditions.” There’s the rub.

If current, market, and conditions are variables,

chance determines the outcome, as in abstract art.

There will be an epidemic, an earthquake, a hurricane;

these will take place, but you can’t say where or when,

and the same goes for a cyber-attack crippling the electric grid,

a terrorist outrage in a tunnel or bridge, the meltdown

of a nuclear power plant, or even a rebellion of angry birds

menacing the human population of a northern California town.

What if the stars should take a powder? Can’t happen?

You never know. “If the Sun and Moon should ever doubt,

they’d immediately go out,” wrote William Blake.

The if is even more important than the doubt.

If you can conceive it, it can be done. Scoff all you like.

If history has taught us anything, it’s that you can kill anyone,

and Ladbroke’s of London will lay the odds.

Acts of God (if you’re a traditionalist)

or black swan events (if you’re a secular humanist)

cannot be predicted. The blather of experts

will do you little good, because

the unknowns are in flux, and the gulf

is sometimes wide between the odds

set by the handicapper for the morning line

and the betting public at the track

when the horses reach the starting gate.

Nevertheless, though playing the ponies has declined

as a pastime, though market crashes

have spooked retail investors, and though

everyone knows the odds are stacked

in favor of the house, people will continue to bet,

and bet big, on races and contests, cards and dice,

games and turns of the wheel, stocks and bonds,

options, rates of exchange, orange juice futures,

elections, murders per capita, jobless claims ,

the number of crates of disinfecting wipes

Clorox has shipped since March 15, 2020

or the number of current ad campaigns

in which part of the pitch is “we’re in this together.”

At the moment I have a side bet on “never bet

against America,” a phrase that has caught on

since Warren Buffett used it at Berkshire Hathaway’s

virtual annual meeting. The phrase frames the crisis

of the day as a wager about who will prevail when

Affirmed and Alydar go head to head for a fourth showdown

or when the Celtics of Larry Bird square off one more time

against the Lakers of Magic Johnson.

The Derby and Preakness won’t be run until the fall this year,

and they won’t be playing the NBA finals in June.

People will miss the games, but they will bet on much else

with cash, or play money, or just in that realm

of the imagination that prefigures the things we do.

2.

Gambling is a natural human instinct, because life

is a gamble in which you will lose your shirt

or draw a third ace to fill a full house

on days equally rare. “Life,” Baudelaire wrote,

“has but one true charm: the charm

of gambling.” All beliefs are bets,

though a bet is not necessarily a gamble.

If the lockdown goes into a third month,

and we get a heat wave, and beaches are closed,

and there’s no sports betting, it’s a safe bet

there will be rioting in the cities

and a big spike in day trading. You can also bet

on the persistence of prejudice, political bickering,

fakery, hypocrisy, bureaucracy, and the power of the lie,

but no one will take the bet, and it’s not a gamble.

You need a degree of recklessness to be a gambler.

Religion is risky, a big gamble,

though not in the way Pascal proposed

and Voltaire refuted. Pascal’s wager is not,

as he tries to sell it, a real gamble.

He would subject a belief in God

to a cost / benefit analysis.

If you bet on God and God exists you win;

if you bet against and you lose, you lose big.

The argument is seductive, but the proposition

has lost all conviction. The risk has been drained from it.

If only self-interest could furnish the grounds for belief!

You might also say that the ends (divinity) stand

in diametric opposition to the means (logic)

in Pascal’s equation, which remains, despite

its flaws, a fascinating subject of contemplation,

like the bust of Homer in Aristotle’s hands.

“God is a scandal – a scandal which pays,”

Baudelaire wrote in his “squibs” (trans. Christopher Isherwood).

“God is the sole being who has no need to exist in order to reign.”

Gambling requires faith, not assurance or certitude

but something finer, rarer: faith, a near rhyme

of truth and death that sounds like fate,

which is how Willem de Kooning pronounced the word.

And what is faith but the opposite of doubt – a force

to press back against the dismal news of the day,

the doubt that arises in the mind of the prophet

beholding the wickedness of the people?

Religion requires risk, like the risk you feel

when you are so deeply involved with another person

that you cannot imagine living your life without her.

The inevitability of loss, a much-misunderstood aspect

of gambling, is not a deterrent but an attraction.

The experience of loss is as potent a stimulant

as the experience of jumping from a low-flying plane

trusting your parachute will work.

3.

A compulsive gambler’s habit is as hard to break

as smoking or drinking, maybe harder. The gambler

believes in the god of chance, which is the wrong god

to believe in. Gamblers act on superstition just as athletes do:

wear a shirt with red in it every Sunday; on a winning streak,

use the same bat, do not shave, eat the same breakfast

every day; change your stance in a slump, though you know

nothing will help in a slump. Skillful poker players

put a game face on a nasty turn of events,

but they do that when the cards favor them, too.

Skill or luck: “People think mastering the skill

is the hard part, but they’re wrong. The trick to poker

is mastering the luck” (James McManus).

To the writer, all is raw material, bad luck or good.

A novelist friend developed a system of winning at roulette,

but it did him more good as the backdrop for a story

than in practice in Monte Carlo.

The philosophical gambler takes the path

of the melancholy pickpocket in a 1950s French movie.

To him, if I may speak of myself this way, luck is a muse,

and Frank Loesser’s song “Luck, Be a Lady”

communicates the risk taker’s situation. The phrases

he likes have two or even three separate meanings, which

he must conjoin, so that Stendhal’s The Red and the Black

is read in the context of the red and black boxes

on a roulette-wheel carpet – or the red and black squares

of the chess board in a match pitting the Russian grandmaster

against the American upstart – and the morning line signifies

not only the bookmaker’s calculations, but also

a verse to speak when the bell tolls for thee.

David Lehman‘s recent books are One Hundred Autobiographies: A Memoir (Cornell University Press, 2019) and Playlist: A Poem (Pittsburgh). He is the editor of The Oxford Book of American Poetry and series editor of The Best American Poetry. He has written nonfiction books about the New York School of poets, classic American popular songs, Frank Sinatra, and mystery novels, among other subjects.

We are happy to welcome DAVID LEHMAN back to our pages.

The Complete History of the Boy

1.

The baby giggled in his crib.

His father walked in. “Why are you laughing?”

“Because,” the baby said, “we all have our joy.”

It was his first sentence.

When the baby had his own bed,

he said children are luckier than grownups

because they get to sleep in their own bed

while grownups have to share.

At four he was asked what he wanted

to be when he grew up. “Santa Claus,” he said.

That was Thanksgiving. By January he thought better of it.

“I never want to be a grown-up because

that would be the end of me.”

It was the age of the aphorism:

“Candles are statues that burn for the ceremony.”

“Saliva is the maid of your mouth.” (It cleanses it.)

This month we’re pleased to bring you selections from Playlist, David Lehman’s new book-length poem forthcoming from University of Pittsburgh Press in April.

By DAVID LEHMAN

[in memory of Paul Violi]

In this my thirtieth year,

Drunk and no stranger to disgrace,

I grin like a fool from ear to ear

Despite the trickle of tears on my face,

Clown that I am, condemned

By Thibauld d’Assole’s command,

Threatened and even damned

By the faker with the crozier in his hand.