Where do your shapes come from? This is a common question I encounter.

I dislodge shapes stored in my body through the act of drawing. These shapes originate from a vast matrix of experiences. There are typically three categories of overt reference: art and archeological objects I seek out through research and travel; landscape; and direct physical experiences (floating on a lake, running in the woods, dance, aging, sex). In the act of drawing, I am thinking through my hands to access this embodied knowledge. The process of ingesting references and experiences, and how they then rearrange themselves within me and come out as these assertive and sturdy abstracted shapes, is an alchemy that remains deeply mysterious to me. They flirt with the figurative, but then swing solidly back into the abstract.

During a studio visit, I unpack for my guest the range of places I have been and the art I have researched. This conversation meanders: from studying quilts in Nebraska and Alabama; to rugged landscapes with geological time marked upon earthly mounds, volcanoes, valleys, and mountains in Guatemala, South Dakota, or the Pacific Northwest (where I was born); to the depths of museums in Istanbul, Tokyo, or New Orleans, where one sees what thousands of hands have made over thousands of years; to ruins in Peru, Cambodia, and Pompeii.

In the paintings, I construct the shapes to stack different layers of female- and male-dominated art histories through my material and paint application choices. Sewing, fabric, dyeing, assemblage, and embroidery all come from a female-dominated tradition, while canvas, paint, and stretcher bars signify a male-dominated history of painting. For hundreds of years, these two sets of artistic conditions carried judgments of differing worth inherent to their materiality and means of production. Smooshing them together within the frame highlights the falsity of these accumulated judgments.

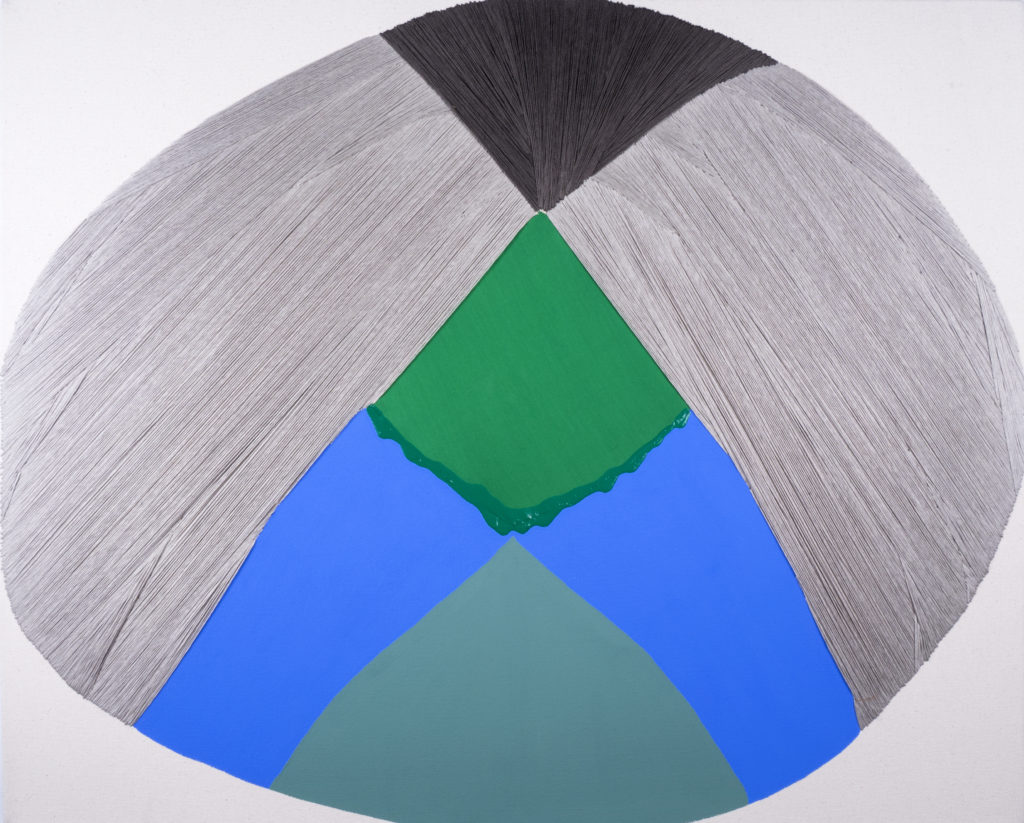

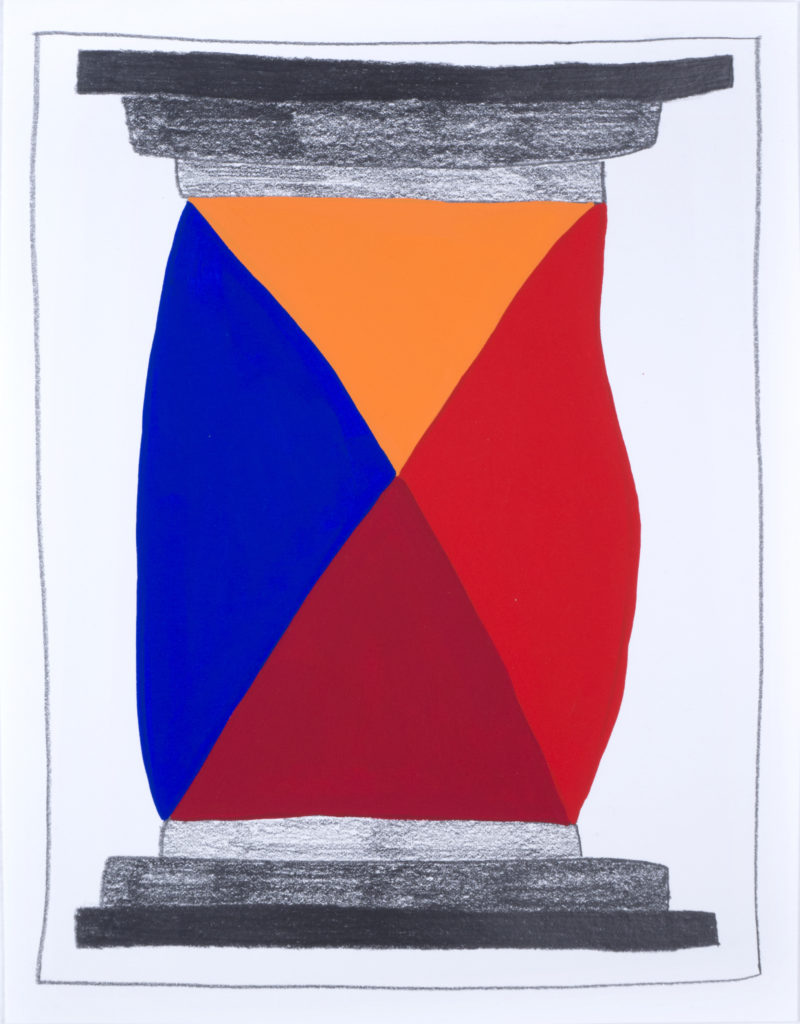

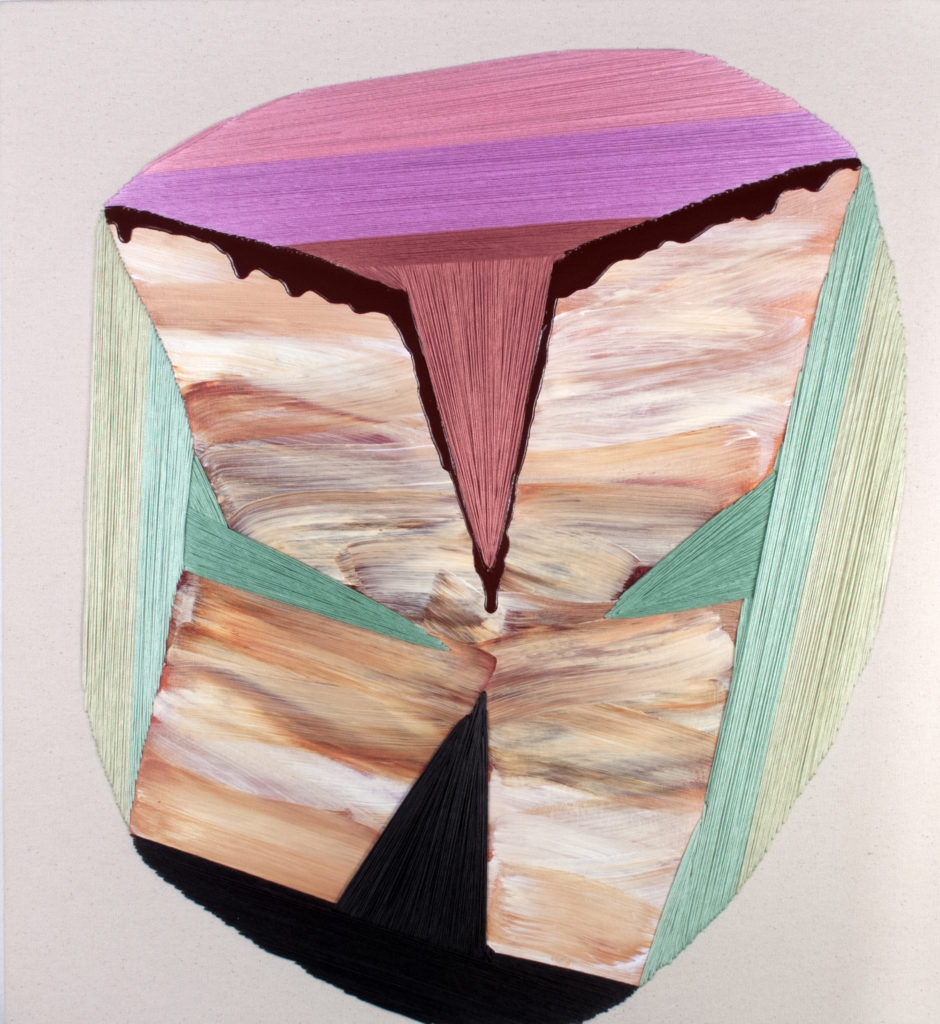

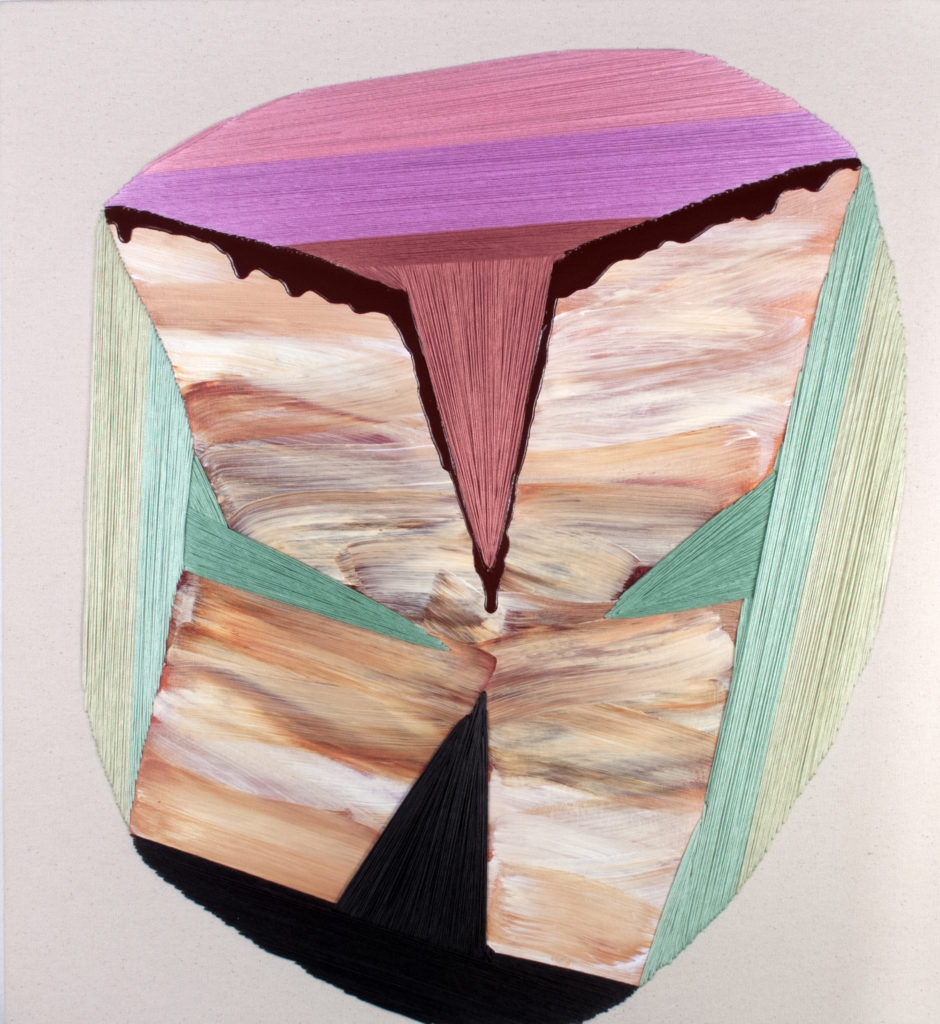

MirrorMirror utilizes a foundation of quilted triangles to produce a visual disorientation: two minimal black flattened mounds support twin peaks thrusting up that paradoxically have a contained wildness that refers to abstract expressionism. Suck Face Sunrise, in color and paint application, quotes the striation of barren mountains in the Southwest and in Badlands National Park, South Dakota. Mirador came to me after I spent a month drawing and learning to backstrap weave on a lake in Guatemala surrounded by four volcanoes. The circular composition and title (Spanish for an expansive view) refer to the wholeness that settles and affirms our spirit when creating personal universes and gaining space in which to view them. The central cone shape in the painting is inspired by a volcano, a form often found in creation myths. The photo paired with Mirador comes from Orcas Island in Washington State, a place I find deeply ingrained and resonant with my abstract shapes, having spent time there for over twenty years. Ancient Future rises out of a year researching pagan iconography in antiquities (often a fertile place for powerful images of women) and these objects’ influence on Renaissance painters. The accompanying caryatid lives in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums.

Lastly, reading and research are paramount to how I locate my human experience. From fiction to biography to theory, I use these sources to build up a conversation. These quotes are affirmations and revelations. They express what I am experiencing in my limited, time-stamped body, and point to the residue of humanity I can leave behind through my shapes.

Suck Face Sunrise. 2015. Embroidery, acrylic, and canvas. 24 x 22 inches.

Badlands National Park, South Dakota, 2014

“There are moments of harmony that rise to the level of serendipity, coincidence, and beyond, and certain passages of time that seem dense with such incidents. Summers and deserts seem best for them.” —Rebecca Solnit

MirrorMirror. 2014. Fabric, black gesso, acrylic, and canvas. 84 x 72 inches.

Gee’s Bend Quilts, Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 2016.

“Some history-making is intentional; much of it is accidental. People make history when they scale a mountain, ignite a bomb, or refuse to move to the back of the bus. But they also make history by keeping diaries, writing letters, or embroidering initials on linen sheets. History is a conversation and sometimes a shouting match between present and past, though often the voices we most want to hear are barely audible. People make history by passing on gossip, saving old records, and by naming rivers, mountains, and children. Some people leave only their bones, though bones too make a history when someone notices.” —Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

Mirador. 2015. Embroidery, fabric, gouache, acrylic, and canvas. 26 x 32 inches.

Orcas Island, Washington, 2013.

“Acknowledging that every aspect of human being is grounded in specific forms of bodily engagement with an environment requires a far-reaching rethinking of who and what we are, in a way that is largely at odds with many of our inherited Western philosophical and religious traditions.” —Mark Johnson

Ancient Future. 2016. Graphite and gouache on paper. 12 x 9 inches.

Caryatid, draped, from Tralles. Roman copy (1st c. AD) of classical Greek original (5th c. BC). Marble. 73 inches high.

“Knowing the past is as astonishing a performance as knowing the stars. Astronomers look only at old light. There is no other light for them to look at. This old light of dead or distant stars was emitted long ago and it reaches us only in the present. Many historical events, like astronomical bodies, also occur long before they appear, such as secret treaties, aide-mémoires, or important works of art made for ruling personages. The physical substance of these documents often reaches qualified observers only centuries or millennia after the event. Hence astronomers and historians have this in common: both are concerned with appearances noted in the present but occurring in the past.” —George Kubler

Amanda Valdez is an artist based in New York. Recent solo shows include Rotherwas Project 1: Amanda Valdez, Ladies’ Night, Mead Art Museum, Amherst College; Hot Bed, Dot Fityone Gallery, Miami; and The Mysteries, Koki Arts, Tokyo. She received her MFA from Hunter College, New York City and BFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.