Curated by ISABEL MEYERS

In this month’s Friday Reads, we’re hearing from our volunteer readers, who consider submissions for print and online publication. Their book recommendations range from poetry collections to recent novel debuts and Flannery O’Connor short stories revisited through the lens of anti-racism. Read on for new quarantine entertainment and keep an eye out for a second round of recommendations from our volunteer readers, out later this fall.

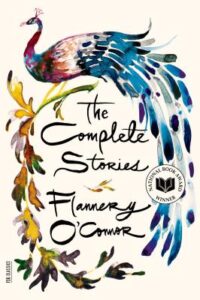

Recommendations: Thin Girls by Diana Clarke; Shiner by Maggie Nelson; Complete Stories by Flannery O’Connor; Cherry by Nico Walker, Dear Edward by Ann Napolitano.

Diana Clarke’s Thin Girls; recommended by Jake Zucker

Two months ago, my friend Diana Clarke published her debut novel, Thin Girls. A feminist-realistic-horror-comedy-tragedy about twin sisters—Rose and Lily—living with disordered eating and navigating celebrity obsession, toxic friendships, diet culture, and the male gaze, Thin Girls is a marvel of voice: the reader follows Rose through a fragmented recovery, rendered endlessly readable by Rose’s cutting irony. “Animals love to follow one another,” Rose tells us. “Their collective is often named for the verb they enact. A group of bees is a swarm… A group of elephants, a parade… Skunks are a stench. A group of thin girls, in recovery, we are surviving.”

Readers unduly focused on the novel’s medical or sociological value ignore Clarke’s expert craft. Rose shifts the novel’s attention to and from pre- to mid-recovery, interjecting summaries of her research on animal behavior (see above) and using weigh-ins as section-headers and time-markers to denote her twin’s dissimilar life and body. (One such heading reads: 18 years old—Lily: 187 lbs, Rose: 75 lbs.) Clarke’s ingenuity serves the aim of much great fiction—to upend unexpected narrative with matching-yet-unexpected form—and hers is a voice we’re lucky to have. Read this book.

Maggie Nelson’s Shiner; recommended by Abigail Frederick

Nothing stays still in Maggie Nelson’s Shiner. In the book’s titular poem, Nelson writes, “Simply / put, I walked into an opening door. / The world is constantly changing shape.” Endings blur with beginnings in these poems: ruined buildings come down at dawn, demolition shares the page with blooming violets and accumulating snow. Nelson mourns and adores in a single breath. The poems ring with both a weariness and a defiant hope, written in a rich diction that demands to be read aloud.

In “The Deep Blue Sea,” which is addressed to her mentor Robert Creeley, Nelson meditates on the rare gift of a teacher who believes you are strong enough to swim on your own. Shiner, published in 2001, was Nelson’s first book of poetry, preceding a number of other imaginative hybrid works. In Shiner, we see a poet standing on the shore—not quite sure yet what she’s seeking as an artist but catching glimpses of it bobbing out on the waves: “one heart- / red buoy.” As I read Shiner, waiting on my back porch between two phases of my life and anticipating an uncertain future, I found a much-needed reminder in its pages. “I am / a beginner,” Nelson writes. “I am / beginning a house I am beginning / to grow filaments.”

Flannery O’Connor’s Complete Stories; recommended by Melissa Holbrook Pierson

Flannery O’Connor’s Complete Stories; recommended by Melissa Holbrook Pierson

Sometimes the universe sends me signals about what I should read. It communicates via the giveaway table at the dump, or boxes left outside cafes. Recently I found something so desirable I snatched it up quickly, sure someone had made a mistake. Who would leave an unread copy of the 1971 550-page Complete Stories by Flannery O’Connor?

I discovered O’Connor’s fiction as a teenager. What I remember of it now is not specific; I only recall a distinct feeling that it was the literary equivalent of being slammed in the head with a board. Her stories were a resounding revelation in an enduring belief that the short story is fiction’s apex form. All I saw then was the gorgeous darkness of her vision, its pitiless gaze on hapless losers of the Southern landscape, the stunningly baroque delusions with which she equipped her characters. The women insisted on drowning in the lake of hard psychological reality rather than throw off the outmoded Southern gentility; the men were blind or grasping or headstrong and usually got the comeuppance they deserved, and if they didn’t, it was the reader who took the punch.

I dug in this time expecting to reacquaint myself with old friends. The stories were every bit as masterfully brutal as I remembered. “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” still stunned with its portrayal of the amoral drifter Shiftlet (her names!) and the fate to which Lucynell Crater willingly delivers her daughter with disabilities. But what brought me up short now was the cavalier racism everywhere. It’s the rare story in which the n-word does not appear, yet it is also the rare story that is not told entirely from inside a character on a collision course with a truth they are too benighted to see. It is their stereotypes—the “lazy” farmhand and the brazen prostitute—that are of a piece with whatever broken conscience is punished in the end. Why had I not had the same response, like choking on inedible bones, when I first read these words in O’Connor’s stories? Meeting this god of my youth helped me answer the question, and it isn’t as pretty as her fiction remains.

Nico Walker’s Cherry; recommended by Chris Skiles

“And it feels like the whole wide world is raining down on you.” This is one of the opening

quotes from Nico Walker’s Cherry, a wild, explicit novel about the perils of war and the temptation of drugs. The quote comes from a Toby Keith song, played throughout the novel as the unnamed protagonist enters the military, graduates from bootcamp, and eventually returns with his battalion as a hero. The story begins with a young man who dabbles in drugs and flunks out of college before deciding to fight in the Iraq War. Once over there, he finds it surprisingly tranquil; the soldiers can even play videogames on base. But that all changes when they enter real “war.” After returning to America, Walker’s protagonist has trouble getting back into the civilian routine; not only does he resume his illicit drug use, but he begins robbing banks and is eventually arrested and sent to jail.

Written much in the style of The Catcher in the Rye, this book follows a young man trying to find his way in a macabre world of sex and drugs, all while not seeming to care about anything. Ultimately, he realizes that you can’t count on people for everything: sometimes you have to rely on yourself. Written from the confines of prison, where the author is serving time for his own bank robberies, Cherry is about dependency on the good in people, and the let-down that occurs when those people do not follow through. One of the reasons I enjoyed this book so much is that it shows how much one can still do from prison—even when all of one’s rights are taken away. The book feels even more relevant in today’s political climate, showing how regular people often pay for the mistakes of the rich and powerful, leaving the American public feeling helpless as a result.

Ann Napolitano’s Dear Edward; recommended by Heather Brennan

Edward Adler’s life changes irreversibly the day his family boards a flight from New York to Los Angeles. In the opening chapter of the book, we are introduced to the passengers on the flight; then, flash forward to late that same evening: the plane has suddenly crashed, killing everyone on board—except twelve-year-old Eddie. From then on, Ann Napolitano’s Dear Edward follows two timelines. The first timeline moves forward with Edward in his post-crash life as he navigates the loss of his family and faces his new status as a nationally famous lone survivor. The second timeline never leaves that fateful flight; the hours between its takeoff and crash span the entire book, giving insight into who the passengers were. We watch Edward through middle and high school as he forms relationships with his aunt, uncle, and neighbor/best friend Shay, at the same time that we slowly learn what happened to make the flight go so horribly wrong. Edward appears trapped between past and present, and the only solution seems to be for him to learn more about the passengers he outlived. He begins to consider what he would like to do with a future he doesn’t feel like he should even have.

Ann Napolitano looks directly at love, loss, and trauma, and does not spare the painful ways that grief can resurface. Part mystery and part tragedy, Dear Edward is ultimately about the impossibility of living a life untouched by others. I believe most readers will remember this book for a long time.