Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

The long New England winter is finally thawing, and here at The Common, we’re gearing up to launch our newest print issue! Issue 29 is full of poetry and prose by both familiar and new TC contributors, and a colorful, multimedia portfolio from Amman, Jordan. To tide you over, Issue 29 contributors DAVID LEHMAN and NATHANIEL PERRY share some of their recent inspirations, and ABBIE KIEFER recommends a poetry collection full of the spirit of spring.

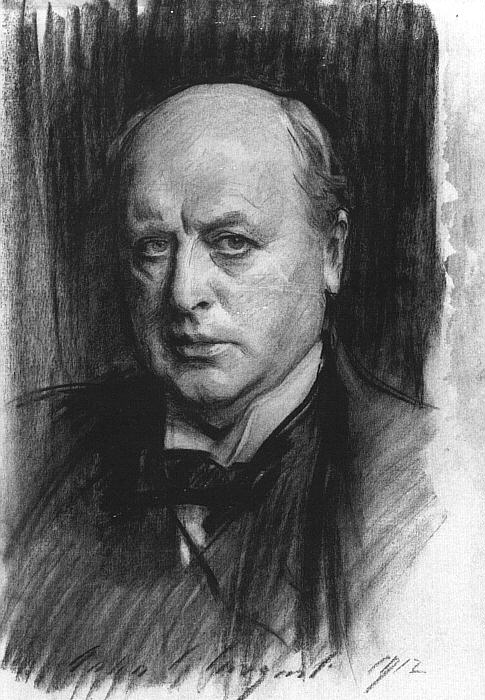

Henry James’ short works; recommended by Issue 29 contributor David Lehman

I’ve been reading or rereading Henry James’s stories about writers and artists: “The Real Thing,” “The Lesson the Master,” “The Death of the Lion,” “The Tree of Knowledge,” “The Figure in the Carpet,” “The Aspern Papers,” et al. His sentences are labyrinthine, and you soon realize how little happens in a story; the ratio of verbiage to action is as high as the price-earnings ratio of a high-flying semiconductor firm. Yet we keep reading, not only for the syntactical journey but for the author’s subtle understanding of the artist’s psyche—and the thousand natural and artificial shocks that flesh and brain are heir to.

All that happens in “The Death of a Lion” may be the loss of a manuscript— or was it a theft?—at a time when there were no copying machines and the burning of a manuscript in a fireplace could mark the dramatic climax of a play. The paradox at the center of the story is that the author toiling in obscurity may produce masterpieces, but when they are recognized as such and he achieves belated success it comes with all the defects of celebrity: his time and solitude are taken from him. He dies two ways.

The stories are parables, but the lessons are ambiguous. That artists have defects, including egos that cannot bear the knowledge of their own mediocrity, is a subordinate theme of “The Tree of Knowledge,” a story about illusions. That the relationship between mentor and student may include an unexpectedly competitive element is one theme of “The Lesson of the Master.” At the end of both these stories, a major character is gobsmacked by actuality.

Anyone who imagines that scholars and biographers are admirably virtuous will not survive a reading of “The Aspern Papers.” Anyone contemplating a career as an English teacher will profit from the fruitless pursuit of the key to an author’s lifetime work in “The Figure in the Carpet.”

What happens when reality and appearance are flipped? In “The Real Thing,” the aristocratic couple hired to model for a portrait of an aristocratic model look less plausible than the married couple who has been hired as servants. Sooner or later the commercial artist has little choice but to flip their roles. The poor pass as noble; their visual appearance conforms to the Platonic patrician ideal. The rich are content to serve them with tea. Is the point that reality and appearance are often at odds? Can we justify fakery as the means to accuracy, itself an illusion? Does the inversion of the classes in “The Real Thing” have a secret subversive meaning? I have long believed that a good essay can be written about this much anthologized story in relation to the greatest Coke commercial of all time, the one proclaiming the soft drink to be “the real thing.” If I were teaching the story, I would give that assignment.

Merrill Gilfillan’s Three Roans in the Shallows, One of Them Blue: Selected Poems; recommended by Issue 29 contributor Nathaniel Perry

I’ve been reading Gilfillan’s work off and on for many years. I’ve read his poems when I could find them; I was awed by his aleatoric prose-birding work The Warbler Road—a collection of what he calls ‘al-fresco essays’—and I’ve published poems of his in the magazine I edit. So when I saw this selected poems from Flood I was excited to have a good chunk of his work in one place. What I was not anticipating was how immersive the book is. This is one of the most well-constructed selected volumes I’ve ever read—organizing the poet’s career indeed in a very rough chronology, but perhaps more by feel and circumstance. One reads the book like a weird novel, or like an atlas, or like a guidebook, or like an aviary, or like a bestiary, or like a bestiary of rivers, or like a daybook, or like all of those things. Gilfillan’s familiar concerns are here— he writes at one point, “Since I cut back / to birds and rivers, life is smooth, / days surer,” and that could certainly be a motto for the whole book (and life goals for me). But this book also isn’t just lyric meditation. It is stranger and more beautiful than that: “Woman on the lawn with wine / pick up summer for a broken book” or “Yes, it’s a beautiful country / … / and our many coffees rarely spill.” Gilfillan is a poet of garrulous concision—can I say that? I’ll stand by it. He is a poet of walks and orioles and good cheese. He is a poet who wants his poems to be like rivers— at once things of easy beauty and also at times inscrutable and rough. My copy right now has as a bookmark a postcard from Japan from one of my oldest friends, a songwriter who was doing a house-show tour of the country last summer. He writes that his tour was an adventure full of “magic, mystery, … and FOOD.” That serves well for a description of Gilfillan’s beautiful book too and as Gilfillan writes about his friends I think too of mine. What worlds a book can hold and touch, and how lucky to be on the porch in spring with this beautiful book. Much gratitude to Gilfillan for breathing and birding and writing, and also, it must be said, to Michael O’Leary and Devin Johnston whose work over the years with Flood Editions has been an uncountable contribution to American poetry.

Elizabeth Galoozis’ Law of the Letter; recommended by contributor Abbie Kiefer

In the title poem of Elizabeth Galoozis’ new poetry collection, Law of the Letter, the speaker recounts a childhood mistake: misspelling a familiar word at the statewide bee. She calls it a joke, being “ditched by the only dependable / knowledge: the order of letters, so confirmable.”

Reading those lines, I made my own mistake, at first seeing “confirmable” as “comfortable.” But confirmation is comfort, right? And dependability, orderliness—those are comfort, too.

The poems in Galoozis’ book, which examine personal and collective histories and our place in the natural world, wrestle with the question of confirmability. What can we know for certain? And what solace can we take from that knowledge? What control does that give us?

Sometimes the answer is not much. Not much certainty, not much control. There’s the seriously ill friend. The wildfires. The limitations of our own capacities. In “Have Yourself,” set during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the speaker tries to remember a “simple recipe, / which I could search for / on the computer in my pocket, / but I can’t admit / one more unknowable thing.”

Where we lack the comfort of certainty, though, Galoozis gives us the comfort of kinship—showing us that we aren’t alone in our desire to make order from the mess. And that we can continue to experience pleasure despite uncertainty. In one of my favorite poems of the collection, “Nine of Pentacles,” the speaker discusses the backyard trees that her wife tends while she enjoys their shelter and fruit. She watches with tenderness and appreciation, glad for the seeds that form so there can be “more fruit / for me to pluck / and squeeze into my rum.”

The speaker goes on to consider how the bees and seeds can’t not participate in the life of a plant. This is their certainty: to pollinate, to germinate. And what is our certainty? We have choices, self-knowledge. That’s beautiful and it’s terrible. We know our own frailty. The fruit—like the tree that grew it, like the gardener who tended it—will, at some point, cease to be. The speaker reminds us of this, but not before giving us a gentle nudge to partake: “we don’t deserve it. / but we don’t not.”