By ALA JANBEK

Translated by ADDIE LEAK

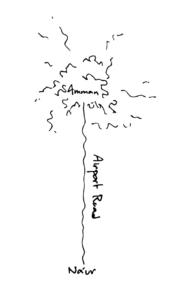

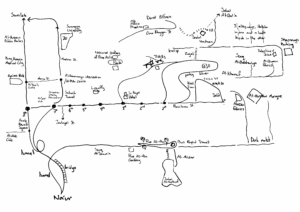

Amman was culture, colorful walls, and distant souqs in the old city where Mama tried to buy everything we needed in one trip. Na’ur was where my grandfather built the mill near a spring, where our home by the hill watches the sun set behind Palestine, far from the chaos of the valley.

I got my driver’s license the summer after my freshman year of college and decided to start taking the family seven-seater to class. I signed up for the 8 a.m. lecture; I wanted to be up early to get a good parking spot by the engineering school.

The SUV was big and empty, and I left home at the same time as the bus. I’d often considered riding the bus to uni, but I’d never actually done it. The SUV meant I could finally explore Amman. I could immerse myself in the art, the colors, the souqs. It felt like holding the keys to the city.

My father was anxious but didn’t want to keep me from my after-class adventures, so he just told me never to go out driving alone. It was good advice, and anyway, I felt guilty about the six empty seats I was dragging around with me.

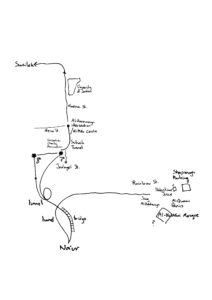

What did I know about Amman back then? The Shabsough parking garage in Wasat al-Balad—the old city—was where my mother would park so we could walk to Souq al-Bukharia, the al-Quraini Supermarket, the Istanbuli and Abu Zahra yarn stores, and the Nazzal gift shop. We would pray at al-Husseini Mosque and then finish out the day with a cocktail of freshly squeezed juices from Palestine Juice. As for my father, he took us to Rainbow Street a few times to eat AlQuds falafel, which he sometimes got on his way to work. One night, when he heard two young men using inappropriate language near us, my father calmly went over to explain how and why their behavior was shameful. How could they talk like that in front of a mother and her daughters? I hadn’t even heard what they were saying.

I would round up my girlfriends, and we would pile into the SUV and type either Rainbow Street or Shabsough Garage into Google Maps; then off we would go.

“Falafel on Rainbow, or should we go for a walk in Wasat al-Balad today?”

“No, not Rainbow—there’s nothing to do there. It’s a ghost town.”

“But it’s too hot in the Balad! And, come on, let’s go someplace classy for once, like girls are supposed to.”

“I think there’s a new spot in Abdali; we should check it out.”

So our trips got rerouted to the Abdali Boulevard, Mecca Mall, City Mall, and Swefieh Village.

And just like that, the old Amman—an empty Rainbow Street and a crowded old city—ceased to be interesting.

You’d Have to Be in Love

She handed him a postcard she’d made herself. She’d drawn a girl on the beach, writing on the sand with a crooked branch. Beneath her, she wrote in English: Find me.

It was David’s last week in Jordan. She’d been working with him on his research in Amman. He bought a notebook from her for three times its price, because that’s what he would’ve paid in America.

So she gave him a postcard.

He sat with his back to the door in the Jadal library. “I know that’s Jabal al-Qala’a even though I can’t see the ruins of the citadel,” he said, looking out the window. “I can’t see them, but I know they’re there: that’s what Amman’s hills are like.”

She gave him the postcard, and he held it with trembling fingers, his voice faint. “You’d have to be in love to send someone this postcard.”

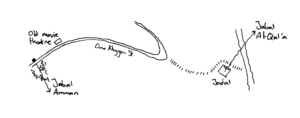

He showed her some thermal maps of Amman’s streets on his laptop, then offered to walk her to her car. They climbed the Kalha Stairs and walked down Omar al-Khayyam Street. The old movie theater was on their right, its concrete screen façade both revealing and concealing the building.

To their left, the buildings parted for a moment, revealing the slopes of Jabal Amman opposite them.

“I’ll really miss Amman,” David said.

It was here, at that moment, that I fell in love with Amman.

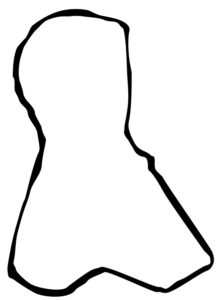

This shape opens up a new phase in my relationship with Amman.

“Stick to the street going toward the cemetery, the Ruwwad NGO building, and the gallery.”

My colleagues set boundaries for me in the neighborhood to keep me safe. It was my first day in Jabal al-Natheef.

My father wasn’t particularly happy about my accepting a job there, especially since I’d turned one down in an air-conditioned office in a glass building under Abdoun Bridge. His creeping anxiety, a remnant of his time as a security officer, was eased somewhat when I told him that the Innovation Space was in the old Circassian neighborhood just in front of Hina Park.

“I know that park,” he said, then added, “Just don’t be a statistic.” It’s what he always says when I start some new adventure, meaning, Don’t be a part of that tragic, tiny percentage we hear about on the evening news.

Mama woke up in the morning to make me a sandwich and a cup of tea for my first day on the job.

Jabal al-Natheef is the only hill in Amman I know inside and out. The borders of the neighborhood are strange. Sidra tells me her house is “on the border between al-Natheef and Ras al-Ain.” Shahad says she commutes from Mars—al-Marreekh, in Arabic—which I assumed was some other, far-off hill, which would explain her grumbling. It turns out, though, that it’s just another neighborhood in Jabal al-Natheef, not more than a ten-minute walk away.

Al-Marreekh, where the municipality’s meeting halls are. I park my car in the small lot next to the building.

At the end of one of the trainings I gave there, my coworker Omar came up to me and whispered, “Don’t leave the building today unless you have security with you.”

“What? Why?!”

“See our friend over there?” He pointed. “He’s wasted.”

It was the young man in the yellow shirt with whom I’d gotten into a heated seven-second conversation earlier, during the training. I’d asked him how he could improve his cell phone store, and he told me he already had everything he needed. “So why come for training?” I said. “Surely there’s something that could be better.”

“I’m telling you: I’ve got it all. Anything you want, I got it,” he said, which is when Omar broke into the conversation.

I usually drive a small electric Ford, but lately Hiba’s been getting up before me to take it to university, leaving me Baba’s Mercedes. Unlike our brother Abdullah, who once made me meet him in the Abdoun Corridor during my drive home to give me the Ford and show off in the Mercedes, I do everything I can to avoid that car.

One day, a boy from the neighborhood knocked on the door of the Innovation Space. He pointed at his friend, who was hiding at the base of the hill, and told me he’d accidentally thrown a rock at the Ford. Good thing it was the Ford. I told him that accidents happened and not to worry about it. There was a tiny, almost imperceptible scratch on the car, and the boy told me again that his friend was the one who threw the stone.

I smiled and reassured him it was okay before closing the door.

An hour later, I went outside to head home. The second boy was still half hidden behind the short wall at the base of the hill. I drove over and rolled down the window. “Hey, it’s okay, no big deal.”

He told me his friend had lied to me and that he was the one who’d thrown the stone.

“It’s fine, not a big deal.”

“It was him, I swear!”

And then, today, I walked out of the Innovation Space and found the Mercedes missing its doors and wheels. A man in the street directed me to a store where I could buy back the parts to get home. I called my father, and he told me that was the only solution: to buy the parts that had been stolen from us.

After that nightmare, I never took the Mercedes to al-Natheef again.

But that wasn’t the main reason I insisted on driving the Ford every morning. The Mercedes didn’t belong in al-Natheef, whereas I found myself cautiously and quietly trying to find my place there.

The Mercedes didn’t belong in al-Natheef, so I didn’t belong in the Mercedes.

After a year and a half in the neighborhood, I no longer wonder if I should buy a snack from the red shop or the blue one; instead, I buy from Abu Hussein, who throws in a date and a walnut for free (because you can’t eat a date by itself).

“The wall even has E + M = ♥ written on it,” said Suleiman.

My students’ discussion topic this session was street art. Yesterday, volunteers had painted a new mural at the entrance to the organization. The students were excited to go see it after class.

“We put plants at the door of our house,” Fatima al-Zahra started.

Suleiman cut her off, saying, “And they got stolen.”

“I wish they’d gotten stolen. I wish! No, they broke them.”

“If we only knew who was scribbling on the walls, me and all the neighborhood kids would beat them up.”

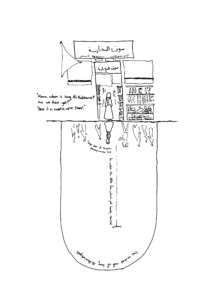

I found pictures of al-Natheef online. “This is the Nawar quarter,” Moayed told me, wrinkling his nose. And he recounted how they’d found a Nawariya, a nomadic Dom woman, in their mother’s bedroom one evening. Malak complained about the Dom kids who would break into their house to go upstairs and pick almonds off the upper branches of their tree.

We were talking about street art in public spaces. I didn’t expect the discussion to get stuck at defining what constituted a public space, without even getting to street art. In al-Natheef, where did the public end and the private begin? How is it that we’re setting boundaries the Dom people don’t recognize? And what would we call the narrow passageways separating the houses: public or private? What would we call the streets themselves? I’d parked the car in the street that day. I could hear a news broadcast issuing from an open window nearby. The walls of the house extended onto the sidewalk. I felt like I was invading the privacy of that home just by choosing to park there.

“Get rid of the Nawar quarter, and that’ll fix al-Natheef.”

I’d asked the students what they wanted to add to the neighborhood to make it better.

“Al-Natheef isn’t fixable.”

“If we get rid of the people like you, it’s fixable.”

“Get rid of all the people who live here; that’ll fix it.”

“Get rid of all the beat-up Sephias and Avantes they drive, and that’ll fix it.”

Then they told me more stories about the neighborhood, as though describing exotic locales to the Sultan.

I try not to be a foreigner in al-Natheef. I try not to be a foreigner in Amman. I try to understand. And love.

Ala Janbek holds a bachelor’s degree in architecture and a master’s in spatial planning. Her grandfather was displaced from the Caucasus Mountains and built a mill in Na’ur, southof Amman, Jordan. She spent her childhood in Rwanda, and currently lives with her family in Na’ur. She works with a sustainable community development organization in Jabal al-Natheef, where she devours the neighborhood stories her students bring her.

Addie Leak is a co-translator of Mostafa Nissabouri’s For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert and Hisham Bustani’s Waking Up to My Distorted City, as well as the curator of a Words Without Borders feature on Jordanian literature. She is based in Amman, Jordan.