Curated by ISABEL MEYERS

Amidst the warmer days and rainy weather, we at The Common are busy preparing to release our spring issue. In this month’s Friday Reads, we’re hearing from our Issue 21 contributors on what books have been inspiring and encouraging them through the long, dark winter. Read their selections, on everything from immigration to embracing loneliness in pandemic times, and pre-order your copy of the upcoming issue here.

Recommendations: The Poetry of Rilke by Rainer Maria Rilke, Transit by Anna Seghers, Stroke By Stroke by Henri Michaux, By the Lake by John McGahern.

Rainer Maria Rilke’s The Poetry of Rilke, translated by Edward Snow; recommended by Peter Filkins (Issue 21 Poetry Contributor)

Rilke is a poet of deep interiority and solitude, one who encourages us to embrace loneliness and isolation in order to more fully dwell within the world. During this past year, I found myself turning to his poems, spending extensive time with them as I had not done since first reading Rilke many years ago. Advising his reader in Edward Snow’s nimble translation of “Entrance” to “step/ out of your room, where you know everything,” he urges our gaze to “raise one black tree/ and set it against the sky: slender alone,” until “you’ve made a world. And it’s immense/ and like a word ripening in silence.”

Not a bad prescription for navigating the stillness of a pandemic, a stillness always on the verge of death, but still holding life lived within its confines. “Nothing is too small” for Rilke’s attention, for through it a bowl of roses is transformed beyond the transitory to become that “which is unforgettable and wholly filled/ with that utmost of presence and promise,/ of offering up, beyond any power to give, of being here,/ that might be ours – our utmost as well.” In an impossible year, the sense of unfolding possibility has been hard to come by. Yet Rilke reminds us that possibility is always there, right in front of us, because it is, well, possible and can vanish, and does, and then returns again, if only we remain patient enough to see it in our midst.

Anna Seghers’s Transit; recommended by Talia Lakshmi Kolluri (Issue 21 Fiction Contributor)

I came upon Transit by Anna Seghers the way I find many of the books I buy, which is to say accidentally, and when I was looking for something else. And then I put it on my bookshelf and didn’t return to it until December of 2020 when time stretched out before and behind me like a long ribbon.

The unnamed narrator, a German man in his late twenties, has escaped from a Nazi concentration camp, swum across the Rhine, been put into a French work camp near Rouen as “half prisoner, half soldier,” escaped again, and walked to Paris. In Paris, he reunites with Paul, a man from the French work camp, and agrees to deliver a letter to another man named Weidel who is staying nearby. The narrator attempts to deliver the letter only to find that Weidel has taken his own life, and that Weidel has a visa and travel funds waiting for him in Marseille at the Mexican Consulate. The narrator eventually makes his way to Marseille and allows himself to be mistaken as Weidel by immigration officials. Transit details the narrator’s attempts, failures, and eventual success in obtaining residence permits, exit visas, transit visas, and safe passage. In his orbit are fellow refugees all trapped in the same loop: trying to book passage on a ship, which is necessary for a transit visa, which cannot be issued until you have an exit visa, which cannot be granted until you have passage on a ship. His life is infused with tremendous sorrow, but because everyone around him has suffered to the same degree, he renders his own experiences as almost not worth mentioning. When Paul explains that he has been issued a “danger visa for the Unites States,” the narrators asks, “Are you in special danger?” He goes on to say, “I just meant to ask whether he was perhaps endangered in a more unusual way than the rest of us in this now dangerous part of the world.”

What struck me the most about Transit is the exacting detail with which Seghers renders the in-between experience of refugees. Rather than focusing on where her narrator is from and where he is going, Seghers homes in on the process of migration itself. She throws into sharp relief that our societies decide who is permitted to stay, who is permitted to leave, and who is permitted to travel in a way that often defies reason. Many of the refugees in Transit are prohibited from staying in Marseille permanently. But they are also prohibited from leaving, or from entering the country that is their final destination, or from passing through the countries that are necessary to get there. Transit is a vital book, not only because it exposes another aspect of suffering caused by the rise of Hitler, but because, as Peter Conrad says in his introduction, “what Seghers saw as an emergency, has now become what we call normality.” Today, long after the end of the last World War, there are many people still traveling to save their own lives, still waiting for safe passage.

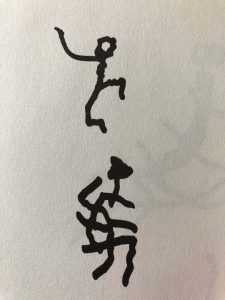

Henri Michaux’s Stroke By Stroke; recommended by Martha Cooley (Issue 21 Fiction Contributor)

“Hardly a painter, hardly even a writer, but a conscience,” said John Ashbery of Henri Michaux, a twentieth-century Belgian literary and visual artist whose interest lay in “pictographic trajectories, but without rules.” I first encountered Michaux’s astonishing work in Stroke By Stroke, a physically and conceptually beautiful little book published by Archipelago Books in 2006. It contains two brief prose-and-verse texts, Grasp and Stroke by Stroke, and their accompanying ink drawings. (The originals were published in French several decades earlier; Richard Sieburth offers a lively and smart translator’s Afterword.) In these works, Michaux takes the reader on a journey that commences when he decides to create a bestiary “from which the verbal would be entirely excluded.” This project soon goes awry. “My various efforts to maintain a grasp, to seize on things, soon aggravated my oppositional bent, and the more I was determined to draw an animal the more I would refuse it.”

Mixing in with these thoughts are visual eruptions, a series of ideogrammic ink drawings that appear, morph, escalate and deescalate, ascend and descend across many pages. The images and words enter a delightfully conflictual dance in which, gradually, a kind of ars poetica emerges: “To release / to loosen / to drain / to unfreeze / to burst to pieces…” The artist opposes any reduction to standardized forms, beliefs, gestures, actions. His aim is always toward multiplicity—“above all not single, / not reduced to one”—and his playful drawings offer a thrilling rebuttal to what he calls “the handcuffs of words,” to “language forming, limiting, grouping.” They’re at once light and dense, comic and serious, antic and contemplative. Always undergoing transformation, the images travel across or up and down the page like dancers whose good cheer is never forced.

Michaux seeks to generate a language that is modest, without pretense, and “not territorial, not aiming to respond to everything…even less to conquer, to convince, to subjugate.” He generates it both verbally and visually, inviting the reader to join him “on ladders that fall but always climb again, ladders one grasps hold of, loses again…them, you, oneself, in space, in all of space.” Reading Stroke By Stroke, I felt invited to travel “toward greater ungraspability”—and in our uncertain times, Michaux’s ease with that is deeply reassuring.

John McGahern’s By the Lake; recommended by Gary J. Whitehead (Issue 21 Poetry Contributor)

Unable to travel over the last year, I happily discovered the fiction of John McGahern, a novelist and short story writer previously unknown to me, and, reading his books and stories, I’ve spent delightful hours in rural Ireland and Dublin. I set out to read all of his books in order, but those plans were dashed by the vicissitudes of shipping in the time of Covid-19. I read his first two novels, The Barracks and The Dark, both of which are moving in their own ways and somewhat autobiographical, but before his third novel, The Leavetaking, arrived, his last, That They May Face the Rising Sun (published in the US as By the Lake) landed on my doorstep. It’s that book I would recommend, though his penultimate, Amongst Women, is also proving wonderful.

By the Lake does what the American title promises: it places the reader by a lake in County Leitrim, which McGahern knew well because he lived there. Slowly, cyclically, he ushers us through a year in the lives of the people who live by the lake. First there’s Joe and Kate Ruttledge: a childless couple who in their retirement have moved from England back to a farm in Joe’s rural Ireland. Their neighbors, Jamesie and Mary Murphy, are also farmers whose children have grown and moved away and whose house is full of antique clocks that all ring the hours at different times. Then there’s Patrick Ryan, a prickly bachelor who is handy at building but less handy at finishing anything he starts, and Bill Evans, a limited and lonely old farmhand whose day is only complete if the bus picks him up for a trip into town. The characters are warm and real; the type of people you’d want for your own neighbors. They visit one another often for tea or whiskey, for cigarettes or a meal, or to bring the bounty they’ve harvested from the land they work. The landscape itself and the lake in the middle of it all becomes just as familiar and beloved, for McGahern’s gorgeous and often repeated images make one feel as if one has lived there one’s whole life: “The morning was clear. There was no wind on the lake. There was also a great stillness. When the bells rang out for Mass, the strokes trembling on the water, they had the entire world to themselves.”

Behind all the joyful moments, there’s a despondency in the knowledge that this simple life is mostly one of the past, and that things end: the cattle, however lovingly raised, are sold for slaughter; children come and go; bright summer ends; and people pass from this idyllic world. The Irish title, That They May Face the Rising Sun, alludes to the Irish tradition of burying a body with its head toward the east, toward the sunrise, the daily reappearance that symbolizes the promised resurrection. In this, his final novel, McGahern wielded the best of his powers to resurrect a lifestyle mostly gone or in the process of disappearing, and to turn the final page made me pine to return to the first, to live by the lake again.