Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

If you’re in need of a deep breath amid the holiday frenzy, look no further. This month, Issue 28 poets and longtime TC contributors OLENA JENNINGS and ELIZABETH HAZEN bring you three recommendations that force you to slow down and observe. Hazen’s picks provide an intimate window into the paradoxical, tragic, and sometimes ridiculous characters that inhabit our world, while Jennings’ holds up a mirror to readers, asking them to meditate on the act of viewing itself.

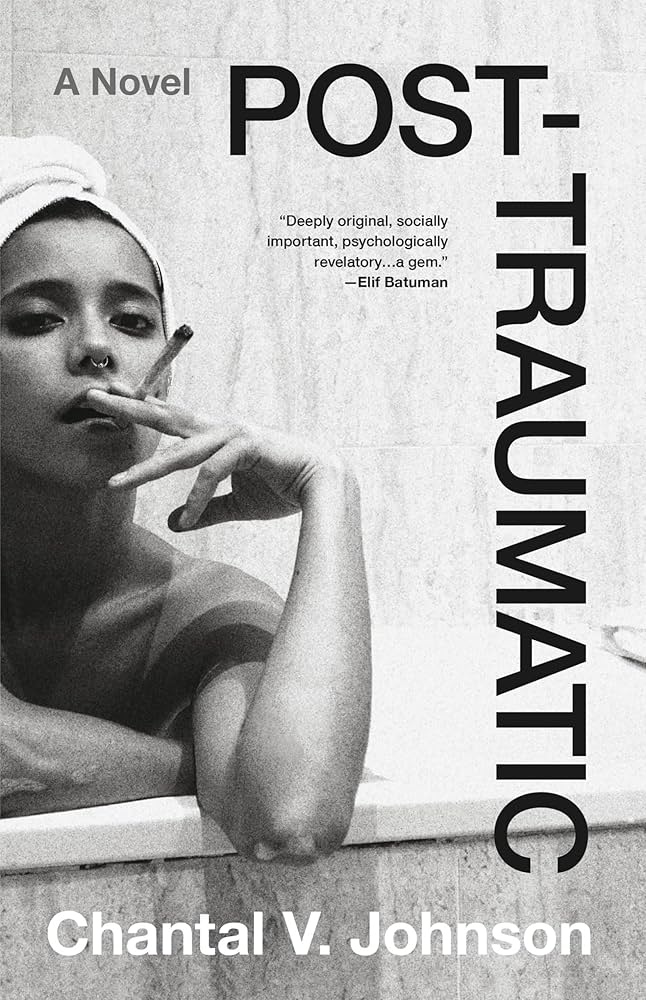

Chantal V. Johnson’s Post-Traumatic and Kate Greathead’s The Book of George; recommended by Issue 28 Contributor Elizabeth Hazen

Typically, I have a few books going at once, and I am almost always at the very least reading one physical book and listening to another. Often, the pairings reveal interesting connections, and my most recent reads—Kate Greathead’s latest, The Book of George, and Chantal V. Johnson’s debut, Post-Traumatic—did not disappoint.

Both books are contemporary, the former out just this October, the latter in 2022, and feature protagonists who are deeply flawed but trying to figure out who they are. They hail from starkly different backgrounds, though, and this determines the starkly different difficulties they encounter as they navigate adulthood.