By PRIA ANAND

The elephant-headed boy was born with the head of a boy.

“I had been expecting you for years,” his mother told him. “By the time you were born, you could practically walk.”

By PRIA ANAND

The elephant-headed boy was born with the head of a boy.

“I had been expecting you for years,” his mother told him. “By the time you were born, you could practically walk.”

By HISHAM BUSTANI

Translated by NARIMAN YOUSSEF

Amman is not incidental. The sayl, the stream that patiently carved a path between seven hills for thousands of years, drew—as waterways often do—the din of life. It was somewhere close to here that the Ain Ghazal statues were found. Nine thousand years old, captivating in their simplicity, they seem to be about to speak as you contemplate their black-tar eyes, the details of their fine features, their square torsos and solid limbs.

By ERICA DAWSON

The month is February and that means

nothing because winter in Tampa is

the same as fall and spring so it could’ve

been easily Thoreau’s “September sun”

or Eliot’s “April is” blah blah blah.

By MARIAH RIGG

Fifty-eight years before Harrison’s granddaughter is born, the U.S. government drops a two-thousand-pound bomb on the island of Kaho‘olawe. It is 1948. On Maui, the shock from the bomb is so strong that it shatters the glass of the living room window, and Harrison, a baby still in his crib, starts wailing in time with the family mutt.

By ALA JANBEK

Translated by ADDIE LEAK

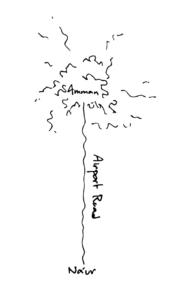

Amman was culture, colorful walls, and distant souqs in the old city where Mama tried to buy everything we needed in one trip. Na’ur was where my grandfather built the mill near a spring, where our home by the hill watches the sun set behind Palestine, far from the chaos of the valley.

According to rule. The terrible safeguard

of the text when placed against the granite

ledge into which our industry inscribed

itself. We were prying choice from the jaws

of poverty, from the laws of poverty.

To take a liberty with lexicon

is remiss in the circumstances

of the curlew

with diminished habitat.

It reprises every day,

and the mudflats

sheeted by the in-

sweep of tide leads it to the mowed

grass in front of the Bantry

is quiet and bright along

the edges, is a beast of silence,

grips a wooden cane

where in the daylight it taps

its way among the stones

and puddles.

By HAIFA ABUALNADI

Translated by ADDIE LEAK

Deferred Migration

Amman is a city of deferred migration with no hope of arriving, depression with no hope of recovery, and the scam that is returnees’ dream of connection. Amman isn’t mine. Because I’m the daughter of parents who left for a time.

When I was just a girl in braids, my hair already settled into its center part, I would walk along the beaches of the Gulf near our house in Mina al-Zour, on the border between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. The Kuwaiti desert stung my feet with its extreme heat and cold. I went to a primary school with only four grades. It had a small pen that held rabbits, two sheep, chickens, and a rooster. On the right side were “barracks” where we had art and vocational classes, and on the left were barracks housing a female nurse and doctor who rarely had office hours. “Home” meant both school and home, and the hugs followed me wherever I went; my mother was with me constantly, day and night. She was a supervisor at the school, and I was her pampered little girl. The other students watched me with envy. My friends were all teachers’ daughters, and we were spoiled: we were given small gifts and made members of the Library Committee, the Scouts, the gymnastics team, and more. The population of Mina al-Zour was scant, so there weren’t many girls at the school.

Out my kitchen window, no pink corridor of smoke.

Along my daughters’ walk to school, redbud trees, native to this state, also known as flamethrowers.

Five miles away, in Newark, the sky above Raymond Boulevard blooms with the discard, the abandoned, rubbish—

No, those are not the right words.