Reviews

What We’re Reading: December 2024

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

If you’re in need of a deep breath amid the holiday frenzy, look no further. This month, Issue 28 poets and longtime TC contributors OLENA JENNINGS and ELIZABETH HAZEN bring you three recommendations that force you to slow down and observe. Hazen’s picks provide an intimate window into the paradoxical, tragic, and sometimes ridiculous characters that inhabit our world, while Jennings’ holds up a mirror to readers, asking them to meditate on the act of viewing itself.

|

|

Chantal V. Johnson’s Post-Traumatic and Kate Greathead’s The Book of George; recommended by Issue 28 Contributor Elizabeth Hazen

Typically, I have a few books going at once, and I am almost always at the very least reading one physical book and listening to another. Often, the pairings reveal interesting connections, and my most recent reads—Kate Greathead’s latest, The Book of George, and Chantal V. Johnson’s debut, Post-Traumatic—did not disappoint.

Both books are contemporary, the former out just this October, the latter in 2022, and feature protagonists who are deeply flawed but trying to figure out who they are. They hail from starkly different backgrounds, though, and this determines the starkly different difficulties they encounter as they navigate adulthood.

What We’re Reading: November 2024

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

With the holidays coming up, many of us turn to books for company on cold nights, or a respite from the stress of the season. If you’re craving an escape into the world of ideas, look no further! This month, our contributors DOUGLAS KOZIOL, CARSON WOLFE, and ANGIE MACRI deliver an eclectic mix of nonfiction and poetry recommendations sure to satisfy and inspire the curious reader.

Nick Pinkerton’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn; recommended by Issue 28 contributor Douglas Koziol

Tsai Ming-liang’s 2003 film Goodbye, Dragon Inn is, in one sense, an elegy to a type of moviegoing no longer possible. Set in a single-screen Taipei theater on its final night, as it plays the 1967 wuxia (a Chinese martial arts subgenre) classic, Dragon Inn, to a handful of people, it would be easy to read the film as overly sentimental or nostalgic. But Nick Pinkerton resists this temptation in his book on the film, which treats the concerns of Goodbye, Dragon Inn with a wonderfully discursive and prismatic critical eye.

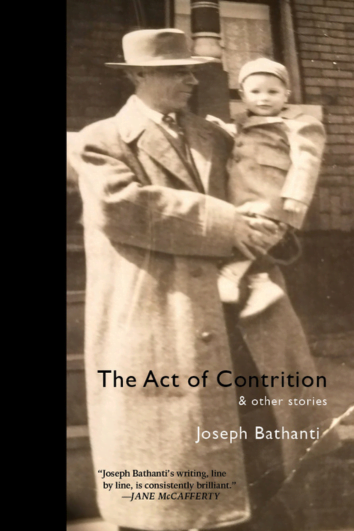

Kaleidoscope of the Heart: A Review of Joseph Bathanti’s The Act of Contrition

By JOSEPH BATHANTI

Reviewed by STEPHEN HUNDLEY

Omega Street. Malocchio. Napolitano and Calabrese. Fritz, Frederico, and Fred. In The Act of Contrition, a collection of linked stories and one novella, Joseph Bathanti reconstructs the mid-twentieth century in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. The Act of Contrition arrives on the heels of Bathanti’s 2022 book of poetry, Light at the Seam, and revisits characters introduced in the author’s 2007 story collection, The High Heart. Bathanti represents East Liberty as a kaleidoscopic dome of terms, places, and names that become familiar to readers, transporting—even trapping—them in a world that is sharp, hostile, and yet, manages to feel like home. Even as readers feel themselves fixed under the pressures of place, they cannot help but be, in equal parts, enchanted by the specificity of Bathanti’s prose. For example, take these lines, from “The Malocchio,” which wed the romance of embodied perspective to the frank realism of the quotidian archive:

“…nothing but brick piles and twisted metal peeked above the mud lots hacked with maudlin footprints and toppled clotheslines—trampled dresses and diapers yet clinging to them. Jackhammers still throttled. The stench of gasoline cloaked the ether—and in the distance, from Penn Avenue, rose the heavenly aroma of Nabisco’s ovens.”

What We’re Reading: October 2024

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

This month, our online contributors CHRIS JOHN POOLE, JULES FITZ GERALD, and LAURA NAGLE recommend three inventive, deeply human books with stories that traverse two oceans—from Japan, to Mexico, to Norway.

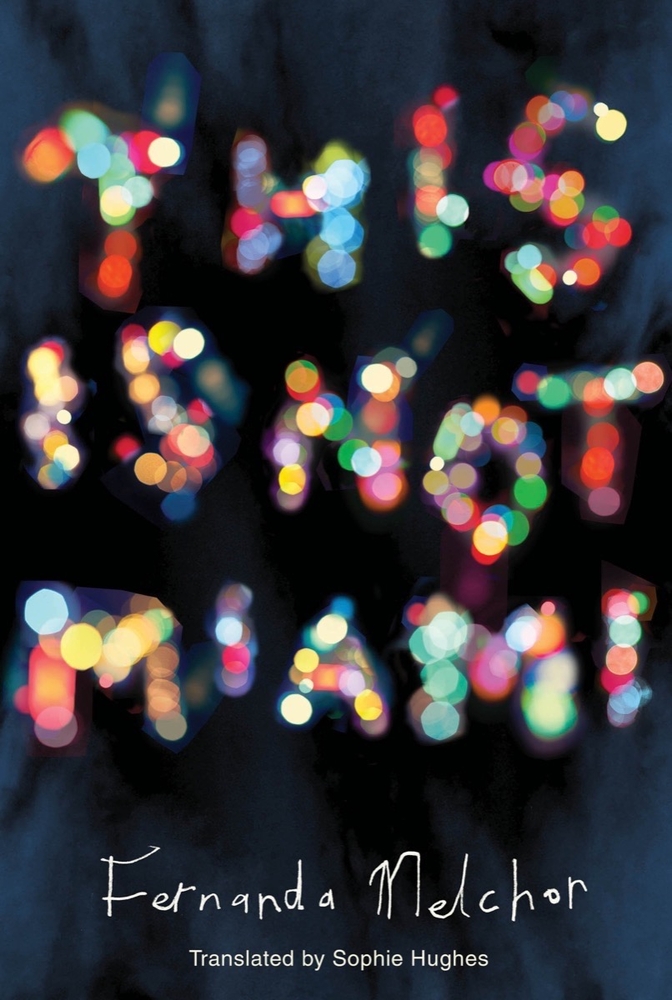

Fernanda Melchor’s This Is Not Miami (trans. Sophie Hughes); recommended by TC Online Contributor Chris John Poole

In her author’s note to This Is Not Miami, Fernanda Melchor writes that “to live in a city is to live among stories.” The city in question is Veracruz, Melchor’s birthplace, a city of cartel violence and political corruption; ritual magic and cold, hard truth. Veracruz’s stories, meanwhile, are those which are gleaned from—and imposed onto—its grim realities.

The stories in This Is Not Miami are crónicas, a genre with no direct equivalent in the Anglophone canon. Crónicas mix reportage and fiction, in a manner akin to gonzo journalism. They favour subjective accounts and firsthand experience over hard data and rigid chronology. Melchor’s crónicas collate rumours, folk myths, and personal narratives, injecting reportage where necessary.

What We’re Reading: September 2024

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

To kick off the autumn column, our contributors bring you three novels that invite unexpected encounters with time. A recommendation from former TC submissions reader SAMUEL JENSEN trains our sights on the future of the American dream; with LILY LUCAS HODGES, we unearth an artifact of historical erasure; and with HILDEGARD HANSEN, we finally transcend history through prose that gropes at the primordial core of life.

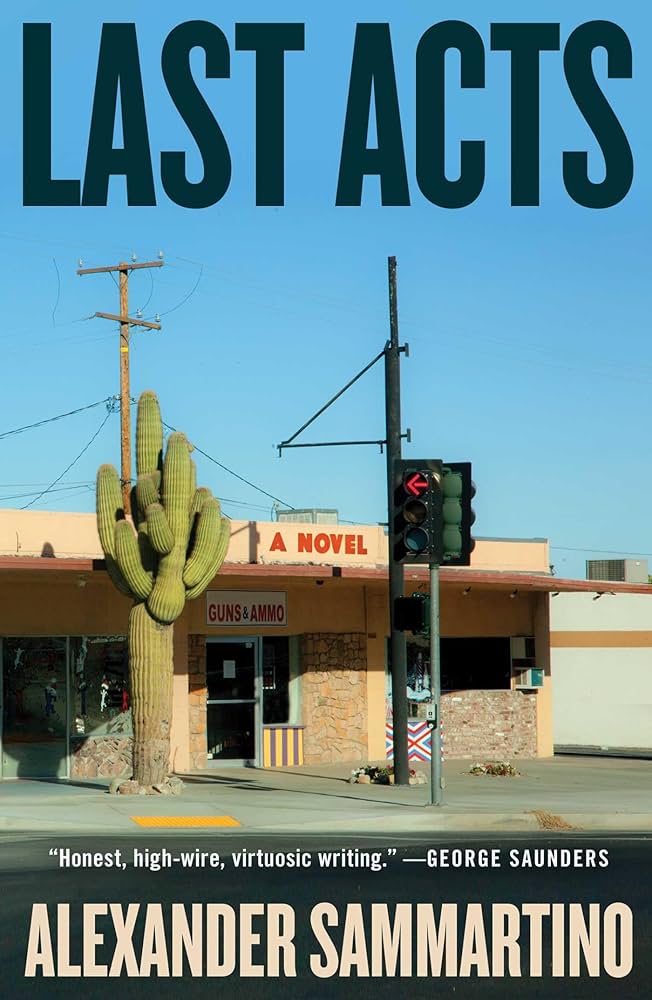

Alexander Sammartino’s Last Acts; recommended by Reader-Emeritus Samuel Jensen.

I picked up Alexander Sammartino’s debut novel, Last Acts, because of the cover. Seeing it at the book store, it was as if someone had walked up the road from my childhood home, aimed their camera across the arroyo, and snapped a picture. I’m from El Paso, Texas and Sammartino’s novel is set in Phoenix, Arizona—two very different places—but still: a sunbleached strip mall with a gun shop in it, burning under a merciless blue sky? It was like running into someone you’re not sure you wanted to see again.

What We’re Reading: August 2024

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

The summer is waning, and here at The Common, we’re soaking in the quiet moments before the final stretch of production for our fall issue. Read on for recommendations from JAY BOSS RUBIN, EMILY EVERETT, and myself, for three pithy books that can help stretch out the season’s end.

What We’re Reading: July 2024

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

July in Western Massachusetts is a month of heightened sensation. Perceptions are focused by the burning and buzzing heat, until it bursts in its own excess, dripping or pouring from the sky. It is an excess that ferments rather than rots, and it is what makes July so intoxicating. The onset of climate change, bringing merciless humidity and monsoon weather patterns, has deepened and darkened this character. Amid this, our Editorial Assistants AIDAN COOPER, CIGAN VALENTINE, and SIANI AMMONS have been reading books that match the month’s potency: storytelling that dazzles, prose that floods and sweeps away the sane, and historical truths delivered in lightning-bolt cracks.

Friday Reads: June 2024

Yesterday, June 20th, marked the official first day of summer! Though the longest day of 2024 has come and gone, the season still promises a plethora of long afternoons and lazy nights. Many of us at The Common cherish this time as an opportunity to comb through our bookshelves and catch up on our neglected To Be Read lists. In this edition of Friday Reads, our editors and contributors share what they’re reading this summer, with recommendations in an array of genres and topics fit for the park, a road trip, a cool refuge from the heat, or whatever other adventures the season may have in store. Keep reading to hear from John Hennessy, Emily Everett, and Matthew Lippman!

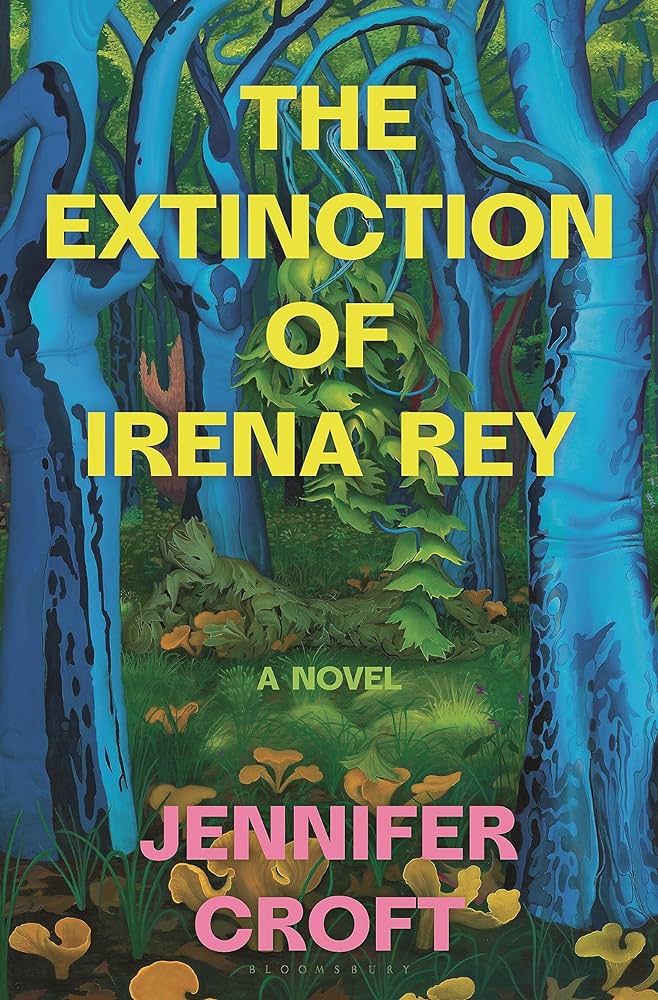

Review: The Extinction of Irena Rey

By JENNIFER CROFT

Review by CHRIS JOHN POOLE

At first, the autobiographical roots of The Extinction of Irena Rey seem simple to trace. This is a novel by writer-translator Jennifer Croft, who works in Spanish and Polish; its protagonist is a Spanish writer-translator. This is a novel from the acclaimed translator of Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights; the eponymous Irena Rey is a Polish literary megastar. This is a novel from a staunch advocate for translators’ visibility; its eight main characters are all translators who seek—and perhaps supplant–their elusive muse.

Yet it is the very abundance of extratextual parallels that makes it so difficult to situate Croft within her text. Unlike Croft’s debut Homesick, a hybrid novel-memoir, The Extinction of Irena Rey provides no single stand-in for its author; instead, a network of interlinked characters echo Croft’s own life. From the novel’s tantalising biographical parallels, countless questions arise: is Irena Rey modelled on Tokarczuk or Croft? Is protagonist Emilia a self-insert, or a novel creation? Ultimately, it seems, these characters are hybridisations of Croft and her influences, as within this novel the lines between self and other, like those between truth and fiction, begin to blur.