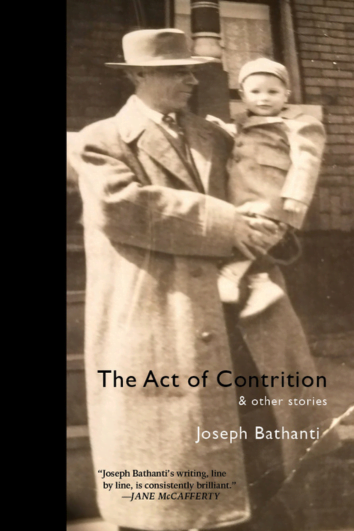

By JOSEPH BATHANTI

Reviewed by STEPHEN HUNDLEY

Omega Street. Malocchio. Napolitano and Calabrese. Fritz, Frederico, and Fred. In The Act of Contrition, a collection of linked stories and one novella, Joseph Bathanti reconstructs the mid-twentieth century in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. The Act of Contrition arrives on the heels of Bathanti’s 2022 book of poetry, Light at the Seam, and revisits characters introduced in the author’s 2007 story collection, The High Heart. Bathanti represents East Liberty as a kaleidoscopic dome of terms, places, and names that become familiar to readers, transporting—even trapping—them in a world that is sharp, hostile, and yet, manages to feel like home. Even as readers feel themselves fixed under the pressures of place, they cannot help but be, in equal parts, enchanted by the specificity of Bathanti’s prose. For example, take these lines, from “The Malocchio,” which wed the romance of embodied perspective to the frank realism of the quotidian archive:

“…nothing but brick piles and twisted metal peeked above the mud lots hacked with maudlin footprints and toppled clotheslines—trampled dresses and diapers yet clinging to them. Jackhammers still throttled. The stench of gasoline cloaked the ether—and in the distance, from Penn Avenue, rose the heavenly aroma of Nabisco’s ovens.”

The collection’s primary speaker, Fritz, provides the vantage of a lovestruck realist. While the collection does give readers access to Fritz as a young man, most stories depict him as a child struggling with fears of abandonment, even as he embraces his independence. The meditations of the speaker take on the trappings of religiosity in a book consumed by family bonds and expectations:

“I waited and prayed—as I had waited and prayed all of my life—for Travis and Rita Sweeney to barge from that impenetrable pall of snow through the kitchen door.”

The tension between freedom and abandon plays out across the collection’s thirteen stories, but perhaps most poignantly in the novella, “Fred,” which opens the book. In rich, painterly prose, Bathanti introduces readers to East Liberty’s deep roots and harsh winter through Fred, the eponymous mutt. The dog is adopted by Fritz’s mother, Rita, and bears her late father, Frederico’s name—as does her son, Fritz.

With so many versions of Fred on stage at once, mirroring and contrasting one another, Bathanti evokes living memory as well as its dark counterpart, vendetta. The collection’s central dilemma is Fritz’s choice to embrace or eschew the weight of family history that is his birthright. Bathanti writes:

“Shouldering vendetta … ends up breaking you. Makes you cry out for mercy. I didn’t need the grief—that hereditary machinery grinding away at me, my soul filled with concrete. I preferred my dad’s resigned bemused detachment: as if he had gauged the underbelly of human nature so flawlessly, that to despise people for being assholes was like despising a bee for having a stinger.”

Functionally, opening the collection with the novella orients readers to the key players and mythology of the collection—Fritz’s parents’ relationship, the wrongs his mother can’t forgive, the church’s role in both unifying and ostracizing the residents of East Liberty, and the economic divisions of the neighborhood. Subsequent stories revisit the lore introduced in “Fred.” The patient accrual of detail grants readers the pleasure of illuminating new facets of the collection’s pantheon of characters—Fritz’s friends, enemies, and relatives—that, by book’s end, attain a complexity that is nuanced and wholly human.

Fritz is simultaneously critical and immersed in the generational grudges, dreams, and limitations of his mother’s “Old World,” Italian family. The insights that Fritz finds throughout the course of the collection relate an understanding of the toll that violence exacts.

Even as a piece of historical fiction that enthralls modern readers in the firmament of neighborhood life, Bathanti flexes mastery in addressing spiritual intrusion. The smoldering ghost of Frederico appears to Rita and Fritz several times throughout the collection and serves as an avatar of all that Rita can’t let go. The mystery of Frederico’s death and the burning of his cobbler shop animates the psychology of Bathanti’s characters. In these moments, Bathanti’s expertise as an imagist and poet amplifies his grounded narrative to create scenes of resonant haunting:

“[Frederico] walked slowly, deliberately, his hands behind his back, a little drunk. Tendrils of smoke wafted from him, flames spouting in the seams and folds of his gray trousers, gray cardigan, gray fedora. Gray skin. Gray whiskey stubble. He smiled or grimaced— his teeth were gray— stopped in front of his daughter, and doffed his cauldron hat in the courtly manner of Old World men. His gray hair sparked.”

Maturing at the intersection of religious fervor and worldly strife, Fritz must negotiate his path with care. He finds himself—like his father—too in love to leave, but too different to ever completely belong. The tearing, binding force of this paradoxical environment has the effect of endearing readers to Fritz—we wish he would run, we see that he won’t, and we love him all the more.

In Bathanti’s world, anyone might be carrying a switchblade. Ghosts appear, accompanied by souls in purgatory. The snow piles high and the frozen streets may kill you where you stand. The forces of good and evil, alike, are depicted as drugs vying for control. Fritz regularly observes his mother under the sway of invisible forces, which he contextualizes in the terms of his world:

“The Devil, with his bag of dope, has hold of her. He’s already got her tied off. The vein throbs indecently in her white arm, her pink dress. In spins the needle. Down goes the plunger. Back roll her eyes.”

In this intense atmosphere of danger, family history is everything, and yet, even memory is a violence to be wary of, lest it devour you. In this world, religion is a tangible force that may offer salvation, but might as easily infest the mind with spiritual possession:

“…like his mother: with her sacramental devotion to getting back at people, making them pay for every wrong she catalogues and nurtures her mouth that assassinates people, then closes against them, like the gates of Heaven…”

Outside of the mayhem of Fritz’s home life, readers are submerged in a class drama that plays out across the various partitions of the neighborhood, which bears the lasting marks of segregation along racial and economic lines. Notably, Fritz’s family exist in a liminal space that provides them some access to all parts of this world—its smoky barrooms and high-end homes as well as its bustling construction sites and bridges haunted by accident and suicide. Through Fritz’s eyes, everywhere is burdened by the past.

As divided as the citizens of East Liberty are, they share a collective, stifling knowledge of one another. Everyone knows exactly where everyone else belongs, and every action prompts a consideration of class. When Fritz is offered a hundred-dollar-bill by a wealthy man, he cannot help but hesitate, wondering at the act’s implications, imagining how his parents would react: his mother, with spite, and his father with neutral acquiescence. Paralyzed by indecision, Fritz divines the wealthy man’s thoughts from his smirk: “Take it or don’t, you worthless fucking peasant. Whatever you do, it’s your funeral.”

When the collection allows escape from the cloistered and hierarchical East Liberty there is an appreciable feeling of possibility. Outside of the neighborhood, the characters imagine new identities for themselves outside of the destinies they have inherited. Whether on the open road, where “thumbing” is a regular mode of travel, or the West Virginia mountains, the closest that Fritz’s mother and father get to the mythical beaches of Florida, these spaces are rife with life and magic.

Readers come to recognize the trademark control of Bathanti’s storytelling, which, time and again, finds its characters in the throes of pressurized scene, rising conflict, and dynamic action, but holds back the final, decisive blow of resolution. When Rita Sweeney abruptly charges into a blizzard, when the police shine their bright lights into a car full of guns and dope, when the hundred-dollar bill is dangled in front of hard-up Fritz’s face; Bathanti brings us to the summit of climax and leaves us there, knowing that his stories resolve according to the rules of his world—rules which tease escape, but promise containment.

These stories bring readers to a place lost to time but familiar in its limitations, breathtaking in its cruelty and its hope. The triumph of Bathanti’s craft is to render a byzantine setting in the crystalline understanding of a native and to impart that understanding to readers who cannot help but feel moved by its drama and invested in its fate.

Joseph Bathanti is the former Poet Laureate of North Carolina and recipient of the North Carolina Award in Literature. He is the author of twenty books, including award-winning novels, volumes of poetry, a short story collection, and memoir. Bathanti is Professor of English & McFarlane Family Distinguished Professor of Interdisciplinary Education at Appalachian State University. He served as the 2016 Charles George VA Medical Center Writer-in-Residence in Asheville, North Carolina, and is the co-founder of the Medical Center’s Creative Writing Program. He also teaches in Carlow University’s low residency MFA Program in Creative Writing in Pittsburgh, where he was born and raised.

Stephen Hundley is the author of The Aliens Will Come to Georgia First and Bomb Island. His stories and poems have appeared in Prairie Schooner, Cream City Review, The Greensboro Review, and elsewhere. Stephen serves as a fiction editor for Driftwood Press and book reviews editor for The Southeast Review. He holds an MA from Clemson, an MFA from the University of Mississippi, and is currently completing a PhD in English at Florida State University, where he is writing a book about the feral horses of Cumberland Island.