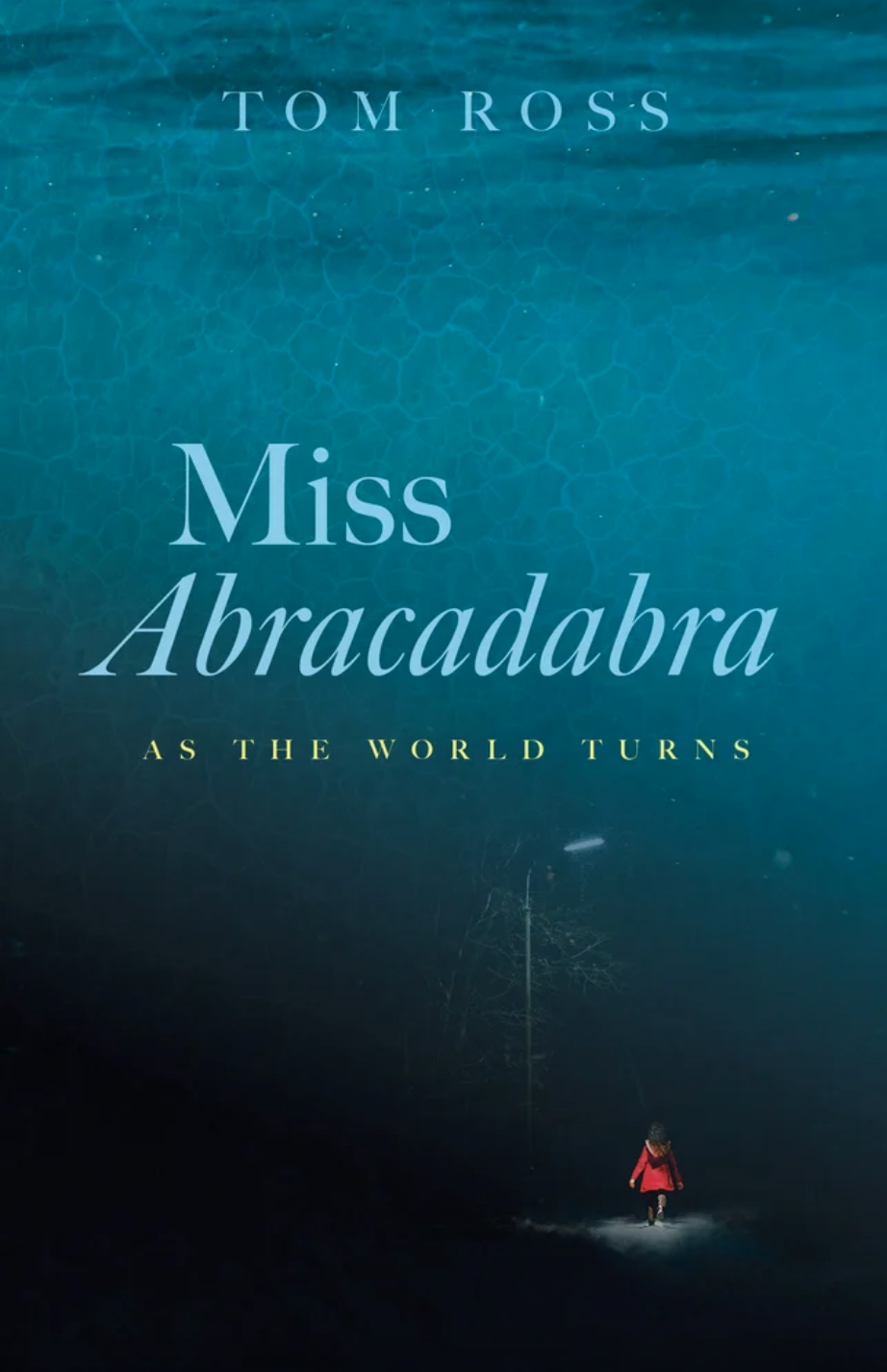

By TOM ROSS

Review by TERESE SVOBODA

My copy of Miss Abracadabra is appallingly dogeared in my attempt to mark its most exquisite parts. Although amazed to discover that this is Tom Ross’ debut novel, I am not surprised that the venerable Deep Vellum published it. Miss Abracadabra is only the second novel they’ve taken on in twelve years that’s not a translation. What magic did Miss Abracadabra conjure to convince them?

Move over, Virginia Woolf. Ross goes deep into the interior with long, long sentences in an astonishing stream of consciousness. Here’s the locale:

That plain now shattered by the highway called 17 East and West, subtending the arc of the sun in its miles of asphalt, into which nothing could ever grow and onto which no living thing could ever venture without being struck dead and ripped into a bloody heap beneath the wheels of cars and trucks racing ever faster to their fleeting destinations, whose drivers and passengers grew ever more indifferent to the fact of that ancient lowland, to the blurring hacked green of the passing mountainside, to the clumps of poisoned weeds crowding the guard rails, to the sound and sight and fragrance of the river to which the horses had once come down to drink now ever more suffocated and muted, indifferent to the blood-red sunset staining their faces and drenching the horizon of the winter sky.

This is the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York during the pre-Civil Rights era, the sticks. You’ve been there, but not with such generosity of spirit nor such precise sentences, which offer heft and clarity, and proceed their sinuous way down the page like one of that region’s rivers, weighted by the pull of print. With infallible syntax and wrought clauses and much interiorized dialogue, Miss Abracadabra heaps on character development instead of relying on a whole lot of plot, which is simple: In a matter of a few months, twenty-something too-adventurous “dunderhead” Rain (short for Lorraine) flees a cad called Zorro Casanova, runs into the arms of Jimmy Love, a long-lashed loverboy on military leave who turns out to be just as fly-by-night, and gets pregnant. In the 1950s’ Black middle class, that is terrifying. Why, even her mother’s teeth-sucking is used as a weapon against her.

Mother’s gesture of infallible disgust, that glaring look with the sharp sound she’d make that folks always think sounds like Tisk tisk, oh quite refined they automatically think, but for her Oh no, it’s wasn’t like some kind of high and proper English whatchamacallit which they always have to go behind and spell different from our good old U.S.A. word for it, it always sounded to her like spitting, a spitting meant to hit her.

Miss Abracadabra’s subtitle is “As the world turns,” also the title of a soap opera that lasted 54 years, from 1956 to 2010, the longest total running time of anything ever to appear on TV. Successful soaps require that each disaster be worse than the last, until the viewer teeters on despair. Miss Abracadabra offers the above disasters in only a few very long paragraphs and much immersion. Time disappears, even inside a single sentence.

But all of a sudden she was not so sure that she was ready, or could get ready, even with a lot of strong drinks, to call home, to leap into the floodtide of silence which would swallow up the words Hello, Mother, which she would scarcely dare to utter, which would sweep her over the edge of the world and then they will drag her down after them into the deep, to sink for what seems an eternity before she would answer, asking each damning question with unflappable eloquence, neither angry, nor happy, nor sad, nor surprised, nor comforting, nor anything at all, and as she plummets down she will feel the dark crushing against her and recall what, at the end of falling, will certainly find what’s left of her there.

It’s not Henry James, thank god, bent on being pedantic and self-absorbed, but full of Jamesian delight in being in total control of the artistic consciousness, with the confidence of a memoir but with all the sumptuous details the novel requires.

And lest you think, my god, Miss Abracadabra’s talking your ear off, Ross changes register at the drop of the fifties’ fedora, to tell another perfectly-pitched story, for example, the one Rain recalls as told by her “terribly bad big brother Sonny”:

These bad hombres what come in here have took over and ruint this town and now they got their beady eyes set on my wife and daughters. Well turn em out I guess, what else? Turn out? she asked. Think about it, you’ll figure it out. Anyhow the Boss says What’re whining to me for why don’t cha just rustle up a posse and ride in an take and string em up?

Overheard or quoted or imagined are many other characters, including a brave Lana Turner, the bartender who hides Rain from Casanova, and her mean-to-the-bone mother, who rides her like an omnipresent conscience: “If Mother were to burst in through the door, as she had ninety eleven times before when she’d been too noisy or too quiet for too long or why in the world wasn’t she all ears when she called…” but it’s Rain and her ruminations that electrify the book. Ross has devised unusual indentations to signify speakers and sometimes irregular spelling and punctuation, but once these are established as deliberate, such aberrations refresh the delivery:

Oh, sweetie, she purred,

scratching behind his ear where he liked it,

I can’t see how all that could be right. I’ll sure have to pick a bone with your whatchamacallit, wing men if I get a chance one of these days.

I presuppose you will, Jimmy Love said.

Talk about a hairy man, she thought, Shoot, laying on him’s about like laying on a bear rug.

“All in good time, my pretty” is the title of the first of the book’s five sections, a quote from the Wicked Witch of the West who’s taunting Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz, suggesting that Dorothy will get what she deserves, but not just yet. A later chapter heading “Handy Man” celebrates what hands can do in a seduction:

Poised for her stirring to meet them as they drew near the places she would have wished them to go if she had known where they were, the places which she could not bear to find them approaching because they would find her already there, the places you were when you didn’t know or didn’t want to know where you were.

There’s also a chapter called “Animal, Vegetable, Mineral,” which title quotes Jimmy Love, the soldier, trying to explain how heat works. She turns it into flirtation:

when a body cold

Like the ones they find and take to the morgue?

Any body, it could be animal, mineral, vegetable. Girl you got a one track mind

And how about you?

Miss Abracadabra’s real coup is capturing the consciousness of a woman as written by the male author. In this gender-sensitive era, that sort of high-wire showing off should trigger a klaxon of impossibility, as egregious as Ariana Olisvos: Her Last Works and Days by David Dwyer that won the Juniper Prize in poetry in 1976. Purported to be the work of an elderly poetess “Ariana Olisvos,” the impersonation raised the hackles of many feminists of that era, but it did win the prize. The audacity of Tom Ross taking on a young girl’s voice—well, you can’t ponder the problem of being pregnant seriously without attempting to “be” a woman. Eventually his relentless use of interiority goes so deep into Rain that the reader doesn’t question the gender divide. As Rain says: “Funny how you can look at everything, she thought, and still not find the answer.” The book wants us to understand Rain as human, someone who finds herself lacking yet tries to make the best of a situation that seeks to get the best of her. She argues with her mother:

And by gosh he’s so IN LOVE with you she [her mother] says. Yes we are with each other I say. Then why not tell him the truth the whole truth. I’m sure he’ll forgive you for putting the finger on him in the first place, what are you waiting for. My whole truth not yours I say.

Miss Abracadabra too deserves a prize.

I’m not telling you how the book ends, not even a spoiler alert, but you’ll come to love Miss Abracadabra in all her wackiness, her troubles-that-she-brings-on-herself, her crushed romantic fantasies, her spirited tussles with her mother, and above all, her very human vulnerability. “As for herself, she was sure that Getting Out of Hell Free would never be in the cards.”

Terese Svoboda is the author of 24 books of fiction, memoir, biography, poetry and translation. Her second memoir, Hitler and My Mother-in-Law, is forthcoming October 7.