By VERNITA HALL

Bottled Water Tastes Better

through a straw

because Things Go Better with Plastic.

Recyclable is the new biodegradable

because the light at the end of the tunnel

only seems brighter in a fairy tale.

By VERNITA HALL

Bottled Water Tastes Better

through a straw

because Things Go Better with Plastic.

Recyclable is the new biodegradable

because the light at the end of the tunnel

only seems brighter in a fairy tale.

The night river calms me with its slow dirty movements.

I walk home briskly, in a black baseball cap.

I work at the fringes of the day. I write poetry in bed

and criticism in the bath.

Among my friends here, I have a man

who calls me love names

in four languages. Once, in a moment, I thought I wanted to die

of his pleasure, but that was a wound

speaking. The history of this place

abounds with wounds.

Mobs of vandals have ransacked the villas.

A very rich man on his deathbed

from a corrupt family who loves the arts

was fed a medicine of powdered pearls.

There’s an itch in my throat like fox fur,

broom bush, cactus whittled to dust,

and my son thinks the city has vanished,

Nariman Youssef speaks to managing editor Emily Everett about her work translating three short stories from Arabic for The Common’s portfolio of fiction from Morocco, in the spring issue. In this conversation, Nariman talks about the conscious and unconscious decisions a translator makes through many drafts, including the choice to preserve some features of the language, sound, and cadence that may not sound very familiar to English readers. She also discusses her thoughts on how the translation world has changed over the years, and her exciting work as Arabic Translation Manager at the British Library.

By SASHA STILES

This month we welcome back contributor Sasha Stiles, whose TECHNELEGY is coming soon in hardcover from Black Springs Press Group.

Completion: Are You Ready for The Future?

An ars poetica cybernetica*

Are you ready for the future?

If you are, today is your day. And when tomorrow hits you like a ton of bricks, you’ll appreciate today even more. Because in reality, tomorrow is a line you walk towards, and now is a line you never see. But you just didn’t see it yet. Reflect. Now the anticipation is here. Finally.

Are you ready for the future?

That depends on how you define ready.

On November 3rd at 4:30pm EDT, join The Common for the virtual launch of Issue 22! Contributors Mona Kareem, Keija Parssinen, Tariq al Haydar, and Deepak Unnikrishnan will join us from all around the world to read their pieces from our Arabian Gulf portfolio, followed by a conversation about place and culture, hosted by the magazine’s editor in chief Jennifer Acker and portfolio co-editor Noor Naga. This event is co-hosted by Amherst College’s Center for Humanistic Inquiry and sponsored by the Arts at Amherst Initiative.

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email via Amherst College, containing information about joining the event. If you’d like to preorder Issue 22, you may do so here.

Mona Kareem is the author of three poetry collections. She is a recipient of a 2021 NEA literary grant and a fellow at the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University. Her work appears in The Brooklyn Rail, Michigan Quarterly Review, Fence, Ambit, Poetry London, Los Angeles Review of Books, Asymptote, Words Without Borders, Poetry International, PEN America, Modern Poetry in Translation, Two Lines, and Specimen. She has held fellowships with Princeton University, Poetry International, the Arab American National Museum, the Norwich Center for Writing, and Forum Transregionale Studien. Her translations include Ashraf Fayadh’s Instructions Within and Ra’ad Abdulqadir’s Except for This Unseen Thread.

Keija Parssinen is the author of the novels The Ruins of Us, which received the Michener-Copernicus Award, and The Unraveling of Mercy Louis, which earned an Alex Award from the American Library Association. She is currently an assistant professor of English and creative writing at Kenyon College.

Tariq al Haydar‘s work has appeared in The Threepenny Review, North American Review, DIAGRAM, Beyond Memory: An Anthology of Contemporary Arab American Creative Nonfiction, and other publications. His nonfiction was named as notable in The Best American Essays 2016.

Deepak Unnikrishnan is a writer from Abu Dhabi. His book Temporary People, a work of fiction about Gulf narratives steeped in Malayalee and South Asian lingo, won the inaugural Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing, the Hindu Prize, and the Moore Prize.

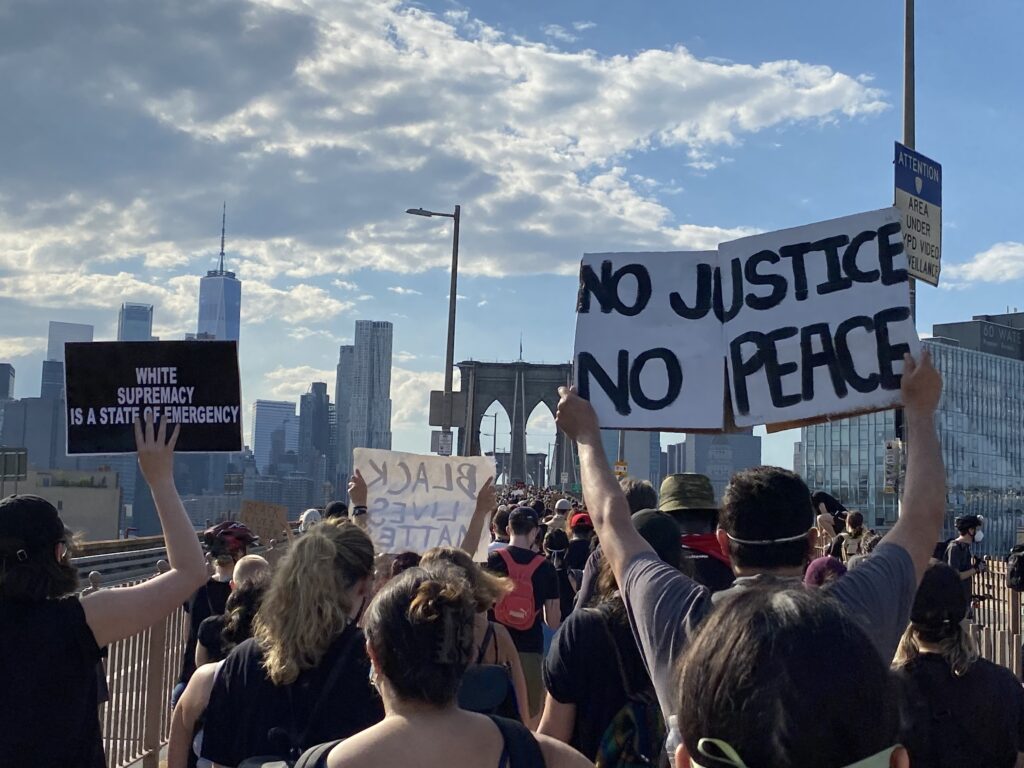

By AKWE AMOSU

New York City

After Kenosha, Wisconsin, 26 August 2020

1. Erasure

I went to the for water,

although I had no thirst, again

unable to find Not sleeping,

roaming restless, hunting

at 2am for on my phone,

no rabbit hole too deep, however

dull, aching tired as though

I had been

Only three days into this,

asked how my was

going, I launched into a tense

that the question even

deserved and saw how hard,

again, I was trying not to the

plain fact that right in front of us,

again, the cop had emptied

his into a human,

now yet shackled

to his hospital bed. That again, a

young had taken down a human

with a military grade yet

away from the scene unhindered.

And that, again, we were being asked

to choke off thoughts, stifle

any sound, stave and belt

the chest to our agitation,

keep breathing because, again,

we

By RICHARD GWYN

Leaving behind the clamor of Mexico City, I catch a bus and cross the wide altiplano. Behind the tinted windows are strewn the blackened remains of trees and cactus, upon which perch large, dark birds. Half asleep on the silent bus, which plows like an ocean liner across the prairie, I think about the birds outside, peering into passing vehicles from their watch-posts. I fall asleep and dream that the birds standing aloft the cacti are truly enormous, and that they have a name that no one can pronounce. Even the local people are confused because they cannot utter, or even remember, the names of these birds, which means, in their language, “those whose croak inspires terror.” It is not known, the people in my dream tell me, whence the name originated, nor have any of the birds been heard to croak; they all remain implacably silent. If one of the birds were to call out, it would signal the end of the current universe, the death of the sun, and the whole terrible process of regeneration would begin once more, following the previous cycles of destruction by (i) tigers, (ii) the winds, (iii) rains of fire, and (iv) water. The inhabitants of the plain, when they die, are roasted in a clay pit and eaten by their relatives and friends. Their livers and other inner organs are eaten by their closest kin. Their feet are cut off and left out for the birds whose name no one can remember, as it is believed that this will prevent them from making their dreadful sounds. Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Dead is in there somewhere, hovering in the debris of my dream.

PAUL YOON interviews RALPH SNEEDEN

In this interview, Ralph Sneeden traces his journey as a poet and essayist, avoiding the destructiveness of being pigeonholed, the inherent politicality of landscapes, and drawing from a pool of resources and poetic techniques to achieve a voice that is at once reflective, visceral, meditative, exploratory, and willing to uncover the veil of comfort and human complexity in an attempt to “testify, to lay bare the quirks, ironies and nuances of history in a way that suggests something new or different about them.”

My thirteen-year-old sister, Mara, wakes me to tell me that she is dead.

She believes this.

I’m twelve, the younger one, though the age difference has never really mattered between us. In the dimness of our bedroom, she’s pressed close to me, her skin warm and a bit sweaty. Just beyond our window–invisible to me now in the dark–the ocean thrashes. I hear and taste it; it makes everything here salty, even the indoors.