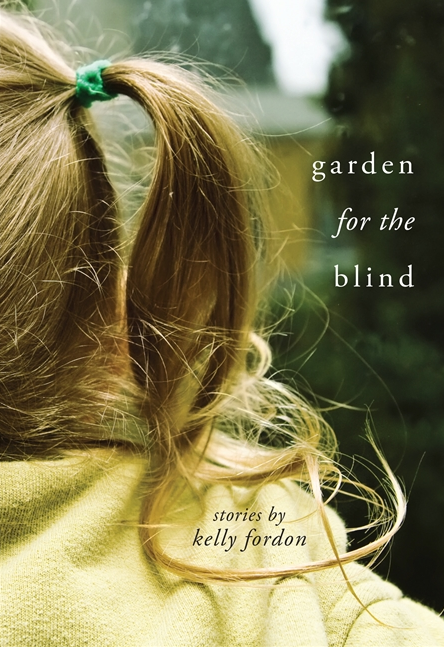

Book by KELLY FORDON

Reviewed by

Garden for the Blind is a more idiosyncratic book than one might realize after a cursory read, a provocative and unconventional meditation on privilege, fate, and the city of Detroit. Kelly Fordon’s debut in full-length fiction is a collection of closely interlinked short stories that follow a small cast of characters from childhood to middle age. One of the satisfactions of reading linked-story collections is the sensation, a bit like time travel, of being guided through someone’s life by someone (think Ebenezer Scrooge and the Christmas ghosts) who knows all the most important moments to show you. Fordon seems to imply this in one of the stories near the end of the collection, “In the Museum of Your Life,” in which a gallery visit inspires the protagonist, Alice, to act as a guide to her own past. Paintings and objects become portals to memory, leaving her with nostalgia, guilt, regret, and unanswerable questions of fate and free will.

The further Garden for the Blind progresses, the more its stories ask the question “did things have to end up like this?” This question addresses the lives of its protagonists as much as the city of Detroit and its close environs, where most of the book takes place. Alice’s story begins in 1974 at an estate in a wealthy—most likely the wealthiest—suburb of Detroit, where her parents are fêting the Vice President of the U.S. and his wife. A grubby mass of protesters stands on the street outside their mansion, kept at bay by Secret Service members. Alice, five, and her sister, seven, are unaware of the class tension on display; in a “let them eat cake” moment, they steal a plate of hors d’oeuvres from the party and offer them to the demonstrators, who accept them facetiously.

This innocent gesture foreshadows Alice’s obliviousness to her privileged status and the harm it will eventually cause. A few stories later, she and her high school boyfriend, Mike, frame an African American scholarship student, making it look as if he dealt the weed a teacher finds in her locker. The student is expelled. Despairing for his future, he jumps into the Detroit River only to have his suicide attempt thwarted by a man who happens to be nearby in a speedboat. Alice and Mike express little remorse when they hear the news of the boy’s brush with death. The amount of drugs they do (PCP, Cocaine, mushrooms, etc.) don’t do anything to improve their awareness or empathy.

It would be difficult to feel a modicum of empathy for these protagonists if Fordon were not adept at showing the emptiness of their lives, the neglect of their parents, and the psychological consequences of both. In middle school, Mike’s alcoholic babysitter beats him so badly he vomits and makes him eat food off of the ground. Alice’s parents, meanwhile, seem completely unaware of her existence; seeing her father is like “bumping into her favorite waiter at Friendly’s.” Mike and Alice are damaged kids, and they end up taking it out—purposefully or inadvertently—on people around them, especially those who are less privileged.

Their behavior is not meant to be allegorical, but it does seem, at least, reflective of the lack of empathy and self-absorption of Detroit’s white population as it abandoned the city, leaving a substantially poorer and African American Detroit in the economic lurch. Fordon’s stories grow in resonance and unease as they approach the present. Racial inequities gain salience in the narrative and in Alice’s mind, like prairie grass encroaching on the decaying city center. Driving through Detroit is “depressing […], like constantly being reminded that Kevorkian has the machine all set up for you,” Alice says in In the “Museum of Your Life.” In “Opportunity Cost,” a socially liberal economics teacher is bullied into signing an anti-“Schools of Choice” petition intended to bar integration of school districts in the early 2000s.

Fordon’s collection is at its most thought-provoking in stories where wealthy suburbanites attempt to come to terms with the dereliction of inner city Detroit from their comfortable enclaves. The cloistering effect these enclaves produce leaves their lives as barren and deserted as the city, which, while remote, still makes its presence felt—to the extent that Alice’s worsening depression seems to mirror its own. This is a strange phenomenon to write about. It isn’t as if Alice feels responsible for what’s going on; as an individual she is powerless against the large, abstract forces that have gutted Detroit. But—given what she did to the scholarship student—she is in the unique position of having contributed concretely to these forces. The essence of her depression is inactivity, a feeling of insignificance (she feels like a ghost as she goes about her day-to-day life), and inner-city Detroit becomes a sort of synecdoche for the childhood misdeed she cannot seem to atone for. Other suburban characters face similar scenarios. The condition of the adjacent city somehow comes to manifest itself in their emotional and spiritual lives; it cannot be ignored.

In the collection’s final story, the eponymous “Garden for the Blind,” Fordon suggests a spiritual response to the excesses and scarcities of present-day Detroit. Alice’s daughter is sent (in a surreal turn of events) to do community service at a school for the blind, which sits across the street from both a Buddhist temple and the house where Mike bought the incriminating baggie of weed so many years ago. When the school’s brand-new garden is vandalized by local kids, monks from the temple sit in the torn-up plots and hold up the plants for the blind students to smell and touch. Despite having seen the crime committed several hours before, the monks did nothing to stop it or to catch the perpetrators; their faith teaches that intervention is futile. The infusion of eastern spirituality catches the reader off-guard, but connects intimately to the book’s message. To ruminate on the course of events, to question fate, and to wonder if things had to end up the way they did (as Alice does) are useless at this point. We may as well treat the past as if it were foreordained, and, instead, become alert to the present. This is the message of the collection’s epigraph, a quote from the Buddha:

There is only one time

When it is essential to awaken

That time is now.

Whether or not this resonates with you as an individual, Garden for the Blind will make you think hard about it.

Tyler Baldwin received his BA in English and Economics from Amherst College. He currently lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.