Book by JEAN WALTON

REVIEWED BY WILL PRESTON

A few years ago, I made an impromptu road trip to a Canadian ghost town called Bradian. Tucked into the Chilcotin Mountains about five hours north of Vancouver BC, Bradian lies at the end of a forbidding 45-mile dirt road and was deserted in 1971 after the local gold mine closed. Despite its near-total inaccessibility, Bradian has become a strangely coveted object since its abandonment. The town has passed from one owner to the next, each with their own ludicrous plan for its empty streets: a retirement community, a sketchy immigration scheme, a drug smuggling operation. And as if rebuffing the unwanted advances of a long line of suitors, the town has foiled every attempt to claim it. (It’s currently on the market for $1.2 million.) Writing about Bradian for The Common in 2017, I saw its bizarre holdout as a parable for the tug-of-war between human conquest and the natural world, a reminder that not everywhere should be subject to the drumbeat of development.

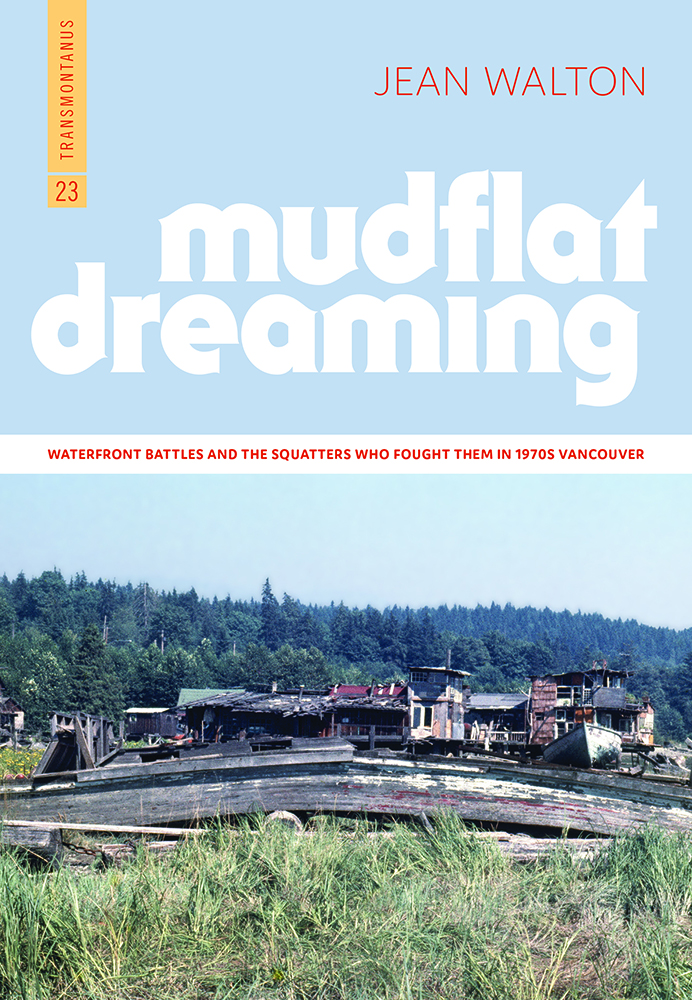

It turns out an early plan to resettle the town had roots in a similar conflict—one of many revelations I had while reading Mudflat Dreaming, Jean Walton’s lively account of civilian resistance to the large-scale urban development that swept Vancouver in the 1970s. Mudflat Dreaming takes its title from the Maplewood Mudflats, a stretch of riverbank just east of Vancouver that was home to a large settlement of artists, environmentalists, college professors, and retirees in the late ’60s and early ’70s. These squatters, dissatisfied with the constraints of contemporary life, constructed rambling homes on the shore from driftwood and other salvaged material. They practiced hippie ideals, with a fluid approach to family, love, and sexuality, and lived in rhythm with the rise and fall of the tides. But their back-to-the-land way of life sparked a titanic clash with Vancouver’s developers and politicians, who had begun to transform the city into the engineered landscape that it is today and had little patience for dissent. According to Walton, the officials briefly considered relocating the squatters far north to Bradian and its sister town, Bralorne, as a compromise, before changing their minds and simply burning the entire settlement to the ground.

I found Bradian’s connection to the mudflats both fitting and ironic, since both places can be seen as stubborn—and visible—rebukes to the accepted logic of modernization. Such resistance is at the heart of Mudflat Dreaming. Through the story of the mudflat settlement, Walton paints the refusal to surrender to “progress” as a battle over legitimacy: ordinary people asserting their right to a chosen lifestyle against the disapproval of the powers that be. (Just the mere assertion can be incendiary; as Walton puts it, highlighting one’s ostensible illegitimacy “calls into question the very grounds of legitimation.”) Nontraditional or countercultural communities are naturally vulnerable. But Walton—who spent her adolescence in Vancouver in the 1970s—observes the struggle for autonomy can befall any neighborhood seen as blocking the tide of urban growth. Residents are left with two equally unwelcome prospects: pack up and leave, or dig in and fight. Mudflat Dreaming takes the latter as its starting point: when the power imbalance between regular citizens and elected officials is so great, the decision merely to stay in one’s home becomes, in itself, a work of political activism.

To this end, Mudflat Dreaming pairs its narrative of the Maplewood Mudflats with that of Bridgeview, a dilapidated neighborhood not far from where Walton grew up. At the same time that the mudflat settlement was fighting for its survival, the citizens of Bridgeview were also locked in a heated battle with Vancouver officials, whom Walton depicts as being more interested in turning the derelict community into an industrial zone than improving the living conditions for the community’s inhabitants. The standoff escalated into an increasingly hazardous game of chicken. Hoping to drive the residents out, the city refused to provide building permits and neglected to maintain the neighborhood’s runoff ditches, creating a cesspool of sewage and waste described at one point as a “biological time bomb.” The residents, for their part, went after the government with the help of a few novel (for the time) tactics, including showing up to council meetings with tape recorders and video cameras and capturing the city’s malfeasance for the world to see.

Walton, who is a professor of film, culture, and gender studies at the University of Rhode Island, draws from this footage, along with two documentaries that highlight the plight of the mudflats. Taken together, these films form the connective tissue between the two narratives of Bridgeview and the Maplewood Mudflats, as Walton examines how media technology can be utilized by ordinary people to “facilitate social change in a way that benefits the least powerful.”

Throughout, Walton overlays her scholarly analysis with personal anecdotes and memories, a wide-lensed approach that transforms Mudflat Dreaming from a straightforward history into something more like an ambling, conversational walking tour. A lengthy middle section focuses on Robert Altman’s 1971 alt-western McCabe and Mrs. Miller, which was filmed just north of Vancouver and used the mudflat settlement as inspiration for its set. Another chapter places the conflict over land use within the broader context of Canada’s history of colonialism and land theft from its First Nations peoples. Elsewhere, Walton considers the Maplewood Mudflats community through the lens of women’s liberation and queer theory, suggesting its liberal setting provided women and queer people with the “aspiration” to break out of traditional gender roles. If these various sections—hopping from memoir to film criticism to interviews with former squatters—occasionally feel cobbled together, it’s appropriate. At one point, Walton quotes a mudflats squatter nicknamed Willie the Collector, who explains how he retrieved “the disparate elements of [Vancouver’s] demolished houses and [brought] them onto the flats” to be repurposed. Walton seems to have taken this aesthetic of “collecting” to heart in her approach; the book’s structure, like the buildings perched along the riverbank, feels charmingly ramshackle.

Yet within this structure, Walton sharply frames the twin struggles of Bridgeview and the Maplewood Mudflats as a David-and-Goliath narrative, one that opens a larger, still-relevant window onto the forces that power the evolution of a city like Vancouver. On one side, we have the city itself. In Walton’s hands, this Vancouver is a sprawling mass of glass and concrete whose thirst for “progress” can only be sated with the destruction of its forests, rivers, and existing neighborhoods; it is a rigid, inhospitable landscape, its politicians almost cartoonish in their my-way-or-the-highway villainy. (“In a municipality of this size, some have to suffer,” one alderman announces, almost apologetically, when confronted over the city’s lack of fiscal support for Bridgeview.) On the other side are neighborhoods like Bridgeview and the Maplewood Mudflats, two communities that view, to varying degrees, an ethos of openness, collaboration, improvisation, environmental stewardship, and community activism as integral to their identity. Walton never goes so far as to declare these ostracized communities the real Vancouver, but the implication, and her loyalty, is clear enough.

It would be easy to portray this conflict as a simplistic choice between the urban and the pastoral, a temptation Walton rightly resists. Mudflat Dreaming is instead more interested in the question of who, among a city’s citizens, developers, and politicians, should be able to determine a city’s identity: who, in other words, deserves the power to make that choice at all. Here in the US, the answer to this question has become increasingly murky in the era of late capitalism and court decisions like Citizens United. The furious opposition to Amazon’s planned incursion into Queens, New York, and its subsequent withdrawal, is a case in point; the company’s expansion, decided in secrecy and without democratic approval, would have upended a city already grappling with widespread inequality and a rising cost of living.

At issue, Walton suggests in Mudflat Dreaming, is the fundamental disagreement over what a perfect city even looks like. Is it a place with sparkling floors and gleaming chandeliers, like the million-dollar homes of business leaders and politicians? Or a community like the Maplewood Mudflats, pieced together with salvaged scrapwood and recycled material? Is it a perfectly oiled capitalist machine that values profit and efficiency above all else, or a society that prioritizes community building and environmental care? These questions were fraught enough in the 1970s, when the residents of Bridgeview and the Maplewood Mudflats squatters faced down a Vancouver they didn’t believe in. In a world increasingly shaped by developers and corporations, Mudflat Dreaming asks us to consider whether our ideal society is one where we get to determine the life that best suits ourselves and our community, or one where those choices—where we live, the way we live, and whether we get to stay—are made for us by powers beyond our control.

Will Preston is a writer, journalist, and critic. His writing has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in publications across North America, including The Smart Set, Smithsonian Folkways, PRISM International, Maisonneuve, The Masters Review, and Glassworks Magazine. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia. A native of Williamsburg, Virginia, Will has since lived in London, Amsterdam, and Vancouver, BC. He is based in Portland, Oregon, where he is at work on his first book. Visit Will at willprestonwriter.wordpress.com.