Review by MEG KEARNEY

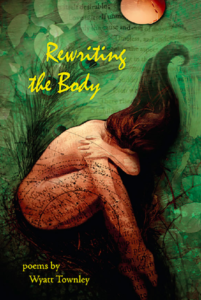

Book by WYATT TOWNLEY (SFASU Press 2019)

What does it mean to “rewrite the body?” To dive deeply and lose ourselves in Wyatt Townley’s fourth book of poems, we must think of “body” as physical human frame; body as door, as house; body as a lifetime’s work, needing to be revised, re-visioned, reclaimed. Rewriting is a daily task, a practice, and the body—the poem/house—source of both refuge and danger, of “both / basement and / torna- / do/,” is also a source of connection with the world.

As poet-architect, Townley is not a formalist, per se, but the “houses” in which her poems reside depend on form to contain their energy, which circulates within her quatrains, tercets, and couplets with an electricity that comes not from spilling secrets but transforming them. Early on in the book, “Black Wedding Train” hints at the largest and darkest of these secrets. The train is:

made of catshit weeds and mud

in its folds boys

circle a girl

facedown in the dandelions

the ants bear witness

to her fisted silence

and the zipper’s scream

The gang rape of a young girl haunts the rest of the collection, and is one of the main drivers behind the need to “rewrite the body.” In keeping with the book’s metaphors, shelter (in a poem by that title) is found in “the smallest room / in the house,” which the speaker has become adept at finding throughout her life, so that she is

at home at any age

in the world’s smallest rooms

where I can turn

a lock like a corner

of this page

As the reader knows, that page is a page of poetry, where “stanza” is also the Italian word for “room.”

To disappear—into a room, a house, a poem—is a form of survival that recurs throughout these poems: “The house was small, but you / were smaller still. You turned // sideways and vanished on a hill” and “you unroll your yoga mat / learning to disappear” (“Meanwhile You While He”). Getting old is another route, as the younger self (to whom the trauma happened) disappears in “Moving Every Tree.” In this poem, tercets with their subtle rhymes follow the older self as a stranger who “is breathing for you until you return,” while the younger “you” climbs out the window and down the downspout. (Humor is not lacking in many of these poems—in “Behind the Shirt,” nipples “strain against the shirt / for a view, noses / through a chain-link fence.” Still, even the nipples wait for death.) A series of villanelles scattered throughout the collection again play with the theme of body as house and its “changing view” as seasons and life cycle toward their inevitable end; even the shoes in “The Closet” have one foot in the grave.

While Townley’s villanelles sing of leaving the “mobile home” of the body, her masterful control of song, most especially its essential silences, is on full display in the book’s title poem. This long poem in nineteen parts is structured as a play of sorts—call it a musical, stage directions included. (After all, “prosody” is Greek for “song.”) Its rewriting of the body first requires a visit to the yard behind the “dream house” of the speaker’s parents, where the silences are as loud as the images (this from section 2):

First what’s not there

no clothesline no swingset

no sandbox no roses no picnic

table and what is a chain

link fence around the overgrown

backyard where one life ended

someone else’s began

your childhood yanked

from you beside the roses

under the walnuts

in front of the sandbox

the swings still moving

as the boys circled up

and pulled down your pants

You remember the ants

Blackout

And from section 4:

It takes a lifetime

to find the feet

the ones that didn’t

run

to come upon

them strike

up a conversation

Such use of space and silence slows the poem’s pacing to a crawl, mimicking the way the mind stops and stutters when overwhelmed by memory. As a rest in music allows what’s been played to linger in the mind, the pauses employed throughout several sections of this “musical” emphasize both what’s been said as well as how difficult those words are to say. “It takes a lifetime,” indeed.

The title poem moves into a different sort of rhythm in section 12 as the speaker explores what “matters” in her world. Here, she uses what James Longenbach (via John Hollander) calls “annotating syntax” in The Art of the Poetic Line. By way of enjambment, poetic lines blur their grammatical units in order to switch or defy the emphasis of the sentence:

It’s the next of kin

and the book these words

have hopped into and the chair

that surrounds you it’s what

unfurls out your window

and again in section 13:

So easy to lose

your place in the open-

ended story written with your breath

to be continued to be

told in wind across a field

Such syntax feels circular, taking one’s breath away, and it’s meant to; the voice becomes insistent and slightly frantic as thoughts and images collide. But there is also a healing taking place, as the speaker realizes in this same section that “the closing of the book / is not the ending of the story” as what matters—love, poetry, nature—is

to be continued and continues

to be told in the curvature of hills

through which a stream is coursing

into your wounds the salve

of the world gliding

your way glacial as recovery

By section 14 the pace slows again, with white space holding a place for silence:

Breath everything is riding on it

under the door winter slides

its white envelope past due past due

While the world brought about the violence that ended a girl’s childhood in an afternoon, it is also the world that brings solace to that wound. The healing is slow, as these words—with so much silence between them—come slowly. But it does come, requiring in part that the speaker love and forgive herself.

Later, the speaker discovers that the part of her with the power to forgive has been inside her all along. In section 16, we are back to an annotated syntax, emphasizing that what’s most important is that “she” finally speaks:

I’ve been with you

all this time more

than your mother

father longer

than your life-

long mate your kids

been with you

thick in sickness thin

in health till death

do you sweetly in

sorrow which breath

will be the last this

one or the one

just after

all we have

undergone what’s

not to love

Such tumbling syntax again leaves us a bit breathless as the “I” essentially and finally speaks to her self, jamming in (as if racing a clock) what has taken her a lifetime to say. That “I” has been mute so long that meanings pile up layer after layer before the body’s last breath—not long off—arrives. Note, too, how the annotated syntax forces us to stress syllables we might not have otherwise (especially those one-syllable end words).

By section 17, the speaker is making peace with the idea of death, realizing she is part of the continuum:

the book of your body closes

as you lay it slowly down goodbye!

on the bed you learned to make as a child

…

on the bookshelf next to those

whose names begin where yours left off

While the curtain closes at the end of this section, that is not the end of this musical: while nightmare and memory still have the power to send “chills up the back / of the arms / chills up the back / of the legs the chills” (section 18), this story ends in section 19 with the “House lights up” and love “raising an eyebrow / across the room.”

There is no real secret to the work of “rewriting the body”—of continually revising one’s life, working to transform and heal what’s wounded us; of learning to sift out what’s important and let the rest go (a sort of house cleaning, one might say); of learning to forgive and to love. Townley tells us “In Extremis” (inspired by Mary Oliver) what we must do, and it is simply this:

…You have

only to breathe—take

the whole room

into the hallways

of your lungs and let

it out—the house

rearranged one breath

at a time. Just breathe.

Then do it again.

The poet William Matthews once said that poetry “teaches us a certain ordinary bravery. It is good for the human spirit to speak the truth in public, in an unquavering voice.” Through Rewriting the Body, Wyatt Townley claims that unquavering voice and thereby reclaims her own life. I marvel at these poems—for their attention to craft, their intelligence, their willingness to be vulnerable, and for their bravery in not turning away from what once lay hidden in the dark. That is the source of the energy that drives these poems, the urgency they embody. We follow this voice into the dark because we trust the hand that leads us there will also teach us that stars exist, even when they are out of sight.

Meg Kearney is author of two books of poems for adults, An Unkindness of Ravens—published in 2001 with a foreword by Donald Hall—and Home By Now, winner of the 2010 PEN New England LL Winship Award and a finalist for Foreword magazine’s Book of the Year. Meg is also author of a trilogy of verse novels for teens as well as an award-winning picture book, Trouper, published by Scholastic and illustrated by E.B. Lewis. Meg lives in New Hampshire and is founding director of the Solstice MFA Program at Pine Manor College in Massachusetts. For more information: megkearney.com.