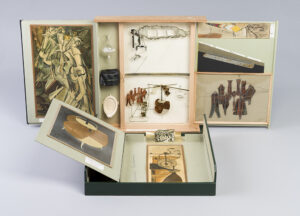

PARTIAL VIEW OF RESTORED HARRISON BOÎTE. MARCEL DUCHAMP (AMERICAN 1887-1968), BOX IN A VALISE (BOÎTE-EN-VALISE) FROM OR BY MARCEL DUCHAMP OR RROSE SÉLAVY, 1963 (SERIES E ). CINCINNATI ART MUSEUM: GIFT OF ANNE W. HARRISON AND FAMILY IN MEMORY OF AGNES SATTLER HARRISON AND ALEXINA “TEENY” SATTLER DUCHAMP, 2016.305 © ASSOCIATION MARCEL DUCHAMP / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY / ADAGP, PARIS 2023. IMAGE COURTESY OF CINCINNATI ART MUSEUM, PHOTOGRAPHY BY ROB DESLONGCHAMPS

“Everything important that I have done can be put into a little suitcase.”

—Marcel Duchamp, Life magazine, 1952

For many years I hardly told anyone that my grandmother’s sister Teeny was married to Marcel Duchamp, and before that to Pierre Matisse, the art dealer son of Henri. Friends I’ve known all my life have stopped me in disbelief when these facts have come up in passing—a disbelief arising not from the facts themselves but from my never having shared them. The first time I ever mentioned the connection to anyone outside the family, I was in college, sitting in the Hungarian Pastry Shop on Amsterdam Avenue with my professor, the poet David Shapiro. “Wait,” he said, “Teeny Duchamp is your great aunt?!” I was surprised he knew exactly who she was.