Curated by KEI LIM

This July, ELIZABETH METZGER, NINA SEMCZUK, and SEÁN CARLSON bring you ruminations on what it feels like to return—to home, to memory, to oneself. As they make sense of their own lives through a poetry collection, novel, and essay collection, their recommendations invite us to contemplate what it means to exist within both change and stillness, and how time itself can wander and fragment.

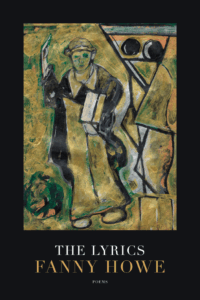

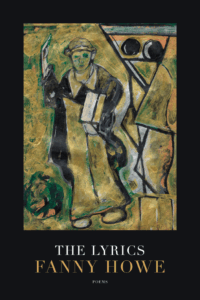

Fanny Howe’s The Lyrics, recommended by Issue 24 Contributor Elizabeth Metzger

It’s early July, and I’m in the middle of moving back to the East Coast. Right now, a few days after the death of the poet Fanny Howe, I am reading her collection The Lyrics, on a screened porch in the late afternoon in the Berkshires, watching geese gather on a tiny red dock. I can hear the voices of parents across the pond teaching their children to fish, to let the fish go. I’m appreciating the element of air as I remember it from childhood, a sort of thickening all around me that feels wearable, welcoming, at times oppressive, a return to an old life from the other side.