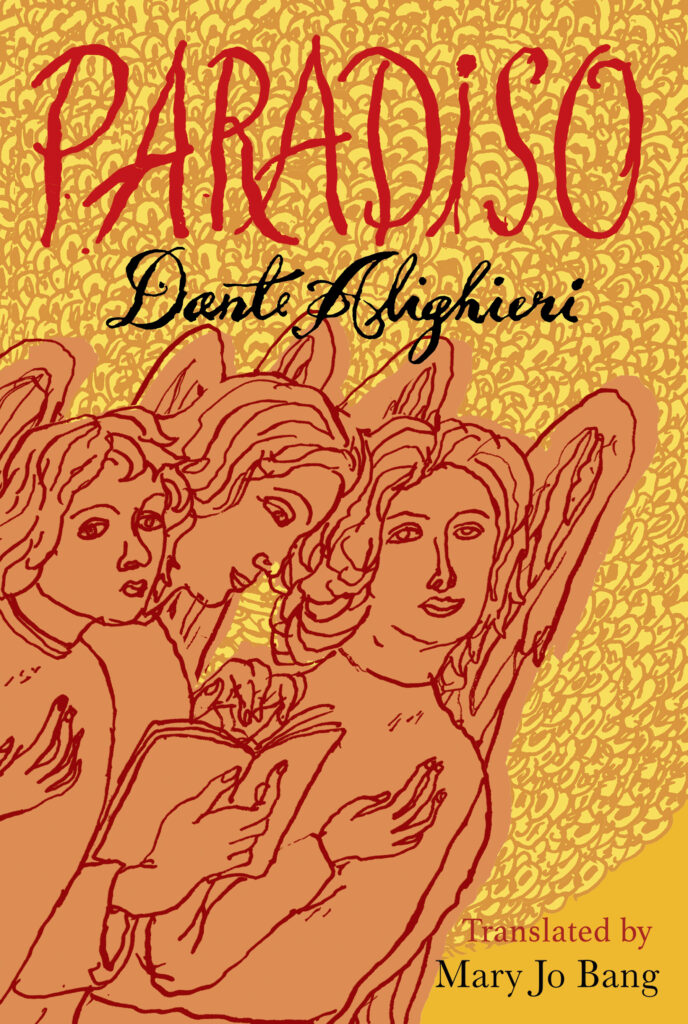

This month we’re honored to bring our readers an excerpt from MARY JO BANG’s new translation of Dante’s Paradiso, out soon from Graywolf Press.

From Paradiso: Canto XI

The first eighteen lines of this canto are Dante’s elaboration of human difference, his lament over the failure of some humans to realize their gifts, and an exultation for the opportunity he’s been given—which is to enter Heaven before he has died.

Thomas Aquinas’s clarification of “where they fatten up” begins at line 22 and continues without interruption until the end of the canto. In lines 124 to 126, Thomas complains that Saint Dominic’s flock, the Dominican friars, are showing signs of ambition and greed, seeking honors and offices. They are wandering away from the tenets of the order, which are to live a life of humility and self-sacrifice. In lines 137 to 139, he says, “You’ll see what has splintered the tree, / And how the remedy for that can be deduced from // ‘Where they fatten up, if they don’t lose their way.’” The tree is the Dominican order, and it has been scheggia (“splintered” or “chipped away at”) because so many of the sheep have strayed. If the monks and clergy remain true to the principles set out by Saint Dominic, they will be enriched with the “milk” of spiritual nourishment and “fatten up” the way sheep are meant to.

Throughout the Divine Comedy, Dante is concerned with the ways in which selfishness destroys the social fabric. He details how people pay for that selfishness in Hell or by having to trudge up the seven terraces of Mount Purgatory. But Dante isn’t only interested in what happens after death, he is also talking about how we live while on earth. His life was destroyed by the petty grudges of partisan politics. As an exile, he was under constant threat of death. He takes great risks in writing his poem because he hopes that by addressing the greed and megalomania that is destroying Italy, he can help put a stop to it. He also knows that this is not a time-limited problem but a timeless one, which is why he wrote the poem in the vernacular—so that, unlike poems written in literary Latin, it would change over time. He said he was also writing his poem in the vernacular so that it could be read by everyone. That is why I translated the poem into the American vernacular.

—Mary Jo Bang