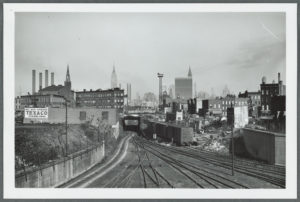

Long Island City, Queens, New York, US

Even if the day was sunny, the air would seem to darken the longer we drove and the farther we bore into the industrial zone. The red brick factories built early in the 20th century were still holding on then, producing staples, electrical circuits, distributor caps and who knows what else. Yet I recall no workers on the streets. There were no stores, no streets, no sidewalks, just ruts. It’s as if the factories were run by ghosts and the only evidence of life was an occasional wisp of smoke rising into gray haze.

I was 19, working my last summer job before I married the following June before my senior year of college. Every weekday morning, I’d begin the journey—for it was a journey to a strange land, not a “commute”—with a ride on the elevated train from my home station in Queens. Soon we left behind the residential neighborhoods with their neat houses and orderly street grid. As we approached Long Island City, the factory buildings closed in on us, nearly scraping the slow-moving train. Once through a grimy, broken window I saw a blouse suspended in the hot breath of a standing fan and couldn’t tell if the arms strangled or hugged as the blouse twirled in a kind of daze on its huge hook.

I left the train at the appointed stop and waited on a bench on a traffic island, joining a few year-round secretaries also employed by the Philip A. Hunt Chemical Company. Our destination had a street address, I suppose. But the building was located so deep within that desolate wasteland that female workers weren’t expected to venture there alone on foot. (Whether the zone was considered too dangerous or the address impossible to find was never explained.) And so the company arranged for a driver to pick us up in a black van, depositing us at the building entrance and retrieving us at 5 pm.

On that small triangle of land, where cars, taxis and buses whizzed by on both sides, I felt safe. Life was normal, civilized: people stopped in delis, glancing at headlines and sipping coffee as they emerged, then striding off with purpose. When Joe, the driver, appeared, he could have been a native guide leading Lewis & Clark into the wilderness. Quickly the bustling streets were swallowed up, the Manhattan skyline just across the East River disappearing as if it had been a mirage. Although we probably took the same route daily, there were no identifying markers along the way–everything seemed to go blank. If I’d been kidnapped and blindfolded, I would have told the police all I knew, that we bumped over cratered streets. We may as well have been on the dark side of the moon.

The Philip A. Hunt Company in New Jersey manufactured chemicals for photo processing and the film industry, but chose to locate an office outpost in Long Island City. The place was a kind of one-floor, above-ground, windowless bunker. Having read Sartre’s No Exit in college, I often thought of that desperate, existential tale as I filed papers and typed letters about chemical orders. Who was I trapped with? And was this for eternity?

I recall only four co-workers: Mr. Sorenson, the suited executive with a vaguely Scandinavian accent, a kind of visitor-emissary from headquarters who was always on the move; Lana, his outpost secretary, who kept her own counsel and, for the entire summer, wore the same navy blue dress and navy blue suit on alternating days, which made me wonder about her salary. And then there was Sheila, the bookkeeper, and Mildred, a typist. Kindly, middle-aged women, they seemed to sense my loneliness and unease, taking me under their wing.

In the airless, unadorned room where we ate our brown-bagged sandwiches—of course, there was nowhere else to eat—they talked about their husbands and grown children, giving me their own recipe-marked cookbooks as farewell presents at the end of that summer. In their gentle solicitousness and desire to pass on their knowledge, they reminded me of Blanche, a supermarket cashier who took pride in her work, teaching me at my first summer job how to assess the weight of grocery items and balance them carefully when packing customers’ bags.

Sheila and Mildred were the one bright spot in my days, whose minutes were heavy weights dragging across the endless desert of eight hours. Once at lunchtime, I thought I’d try stepping out for a change of air, only to flee back inside to escape the pervasive, stomach-turning odor that reminded me of hot dog food left out to spoil.

When a siren pierced the air for many minutes, its urgency apocalyptic, I overheard Mr. Sorenson talking in a low tone to Lana about a serious accident that had occurred within the zone. Some other office workers—who remain faceless in my memory—began to whisper about fatalities. I had envisioned the other buildings as sealed off, too, their occupants hidden, and so, as if telephones didn’t exist, I wondered how the bad news had reached us. Another time, seeing light flash too brightly off a typewriter’s metal carriage, I silently panicked, my mind leaping to one thought: nuclear blast. Every dust mote lay suspended and I felt that I was watching myself under a glass dome where I would no doubt die with Lana, Mildred and Sheila, my No Exit companions. Less than a minute later, the office soundtrack—speech, typing, shuffling of papers—returned.

That summer job was the toughest—harder than my job as a Dictaphone typist at the V.A. over the previous two summers, where I listened to the psychiatric reports of outpatient veterans. I’d taken the chemical company job to avoid hearing those sad stories poured again into the well of my ears. But at the V.A. at least I could escape at lunchtime into the “real world” of Manhattan streets. I had no such release at the chemical company, where I lost any sense of control or self-determination. Taken in. Led out. Taken in. Led out.

In the immediate years afterwards, searching for full-time employment during the city’s bankruptcy, I compared all job prospects to that experience working in a dying industrial zone that, happily, has vanished.

Maria Terrone, the author of four books of poetry, has had work in such magazines as Poetry and Ploughshares, and in more than 25 anthologies. Nonfiction credits include Green Mountains Review, Witness and Litro (UK).