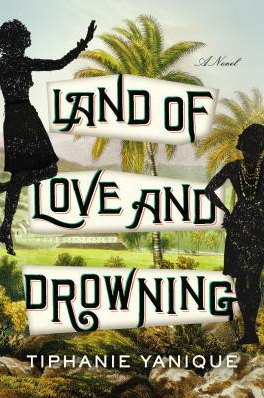

Book by TIPHANIE YANIQUE

Reviewed by

It’s hard for anyone to write a magical realist novel today without inviting comparisons to Gabriel García Márquez. Especially in the wake of his death this year, the Colombian literary giant has been mythologized as the master of blurring the lines between reality and fantasy. Tiphanie Yanique’s debut novel Land of Love and Drowning is a magical realist work that calls to mind García Márquez, yet still manages to stake out new territory—both geographic and literary.

Like One Hundred Years of Solitude, Yanique’s novel is a multigenerational saga.Land of Love and Drowning traces the story of a Virgin Islands family over six decades of the 20th century. The novel opens in 1917, just as the islands of St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix are transitioning from Danish to American rule. When a shipwreck kills Captain Owen Arthur Bradshaw, patriarch of the Bradshaw family, and his wife dies soon after, sisters Eeona and Anette are orphaned and forced to fend for themselves. Yanique’s novel follows the lives of these two women as they attempt to work their way out of their newfound poverty, experiencing a string of ill-fated love affairs along the way.

These two strong-willed sisters are the novel’s most prominent voices. We also hear from their half-brother Jacob, and from an omniscient narrator who is eventually revealed to be the collective voice of the island’s “old wives.” This last choice, doubtless a wink at the expression “old wives’ tale,” signals that this is a novel in which it’s often impossible to tell the difference between myth and reality.

The novel’s first scene, in which Captain Bradshaw witnesses a demonstration of static electricity, is typical:

Science is just a kind of magic, and magic just a kind of religion, and Owen Arthur knows all about this because Owen owns a ship and men who spend their lives on water know that magic is real.

This idea that “magic is real” comes up again and again. For instance, each of the two Bradshaw sisters possesses a gift straight out of a fairy tale. While Anette can sense future events before they happen, Eeona has a siren-like beauty that captivates nearly every man she meets.

“Men will love me,” Eeona says. “It is the magic I have.” When she begins working at a local tourist restaurant, her captivating looks prove to be a boon for business:

She was so lovely to look at, walking among the tables or sitting up in the office going over the bills. She made people hungry, so the restaurant business boomed. And she made people horny, so the rooms boomed louder.

Is Eeona’s beauty truly a supernatural gift, or is this beautiful woman’s skill with men so impressive that it merely seems magical? Yanique never makes this entirely clear, and it’s lines like these that show us how slippery the distinction between fantasy and reality can be.

The first half of the novel feels eerily similar to One Hundred Years of Solitude: like García Márquez, Yanique spends plenty of time chronicling a series of doomed romances and incestuous relationships. Eeona is haunted by an Oedipal infatuation with her short-lived father, then later falls in love with a mysterious man who bears a strong resemblance to the mythical spider Anancy, a figure from Caribbean folklore. Meanwhile, much of the novel is spent chronicling the epic romance between Anette and her half-brother Jacob.

When World War II comes, Anette and Jacob are wrenched apart: Jacob travels to America after being drafted into the U.S. Army. There, he experiences the ugliness of segregation and the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement. Back at home, Anette sees tourists start to come to the Virgin Islands in droves, buying up beaches and houses. The old wives say disdainfully, “As far as we could see, that’s all the Americans seemed to do—drink rum and buy up land.”

It’s in this later part of the novel, in portraying the clash between tourists and locals, that Yanique truly differentiates herself from García Márquez and other magical realists. The first half of the novel is more wide-ranging and covers the familiar subjects of love, poverty, and magic—staples in many García Márquez novels. But in the second half, as Yanique delves into the conflict over tourism in the Virgin Islands, the novel picks up momentum and develops a strong focus.

As Americans buy up the Virgin Islands’ land, they start to dominate the stories told about the place as well, telling of the beautiful beaches and beautiful women but not much more. Anette eventually becomes a history teacher, and is forced to teach a standardized curriculum in which the Virgin Islands hardly merit a footnote. When it comes to the history of Anegada, the island her mother comes from, Anette is painfully ignorant:

There was no course where she could study Anegada history or Virgin Islands history at all. She taught American history and a general Caribbean history that focused mostly on the pirates of Jamaica. That is what there was for her to teach at the Anglican school.

Television ensures the domination of American popular culture, and the Virgin Islands are often shunted to the side. As another Virgin Islander tells Anette:

Look we over here in the USVI. We think we free. But the TV, just look at the TV, and you seeing that we is the United States V.I. and that mean we don’t have nothing.

Storytelling is a powerful thing, the novel reminds us. Through these representations of the Virgin Islands, we see that the stories told about a place—in books, in movies, on TV—have the power to transform or even erase a people’s identity. When Anette’s daughter Ronalda travels to America, she’s exposed to a new set of stories, stories that weaken her connection to her homeland. Ronalda sees books, newspapers, and television shows filled with images of American blacks, but Virgin Islanders are almost entirely absent from American media. For Ronalda, it seems as though “the Virgin Islands barely existed at all.”

The Virgin Islands have few well-known writers, historians, or moviemakers of their own, and Yanique’s novel alludes to the danger inherent in depriving a place—through political and economic colonialism, for example—of the opportunity to tell its own stories. With Anette’s help, we see how Virgin Islands history has been forgotten and that the only representations of the islands in popular culture are unflattering. The novel’s climax in part concerns the filming of Girls Are for Loving, a pornographic movie set in the Virgin Islands, based on a real film from 1973.

When Anette, her husband Franky, and other Virgin Islanders are invited to be extras in the movie, they’re initially unaware that it’s a work of pornography. Anette is thrilled to be featured prominently in the movie posters: “That Girls Are for Lovingmovie was meant to make us. To make us real … That poster was a magic.” And she anticipates the transformative impact that this movie will have on the identity of the Virgin Islands: “This movie was going to make us the finest piece of land in the region. A place of culture. Worthy of Hollywood.” The cruel joke, of course, is that the movie merely reinforces American stereotypes of the islands as a place for sex and drinking on exotic beaches.

American tourists continue to clash with Virgin Islanders throughout the last part of the novel. One of the novel’s turning points comes when Anette’s family journeys to a nearby beach, an almost sacred ritual for them: “It was more than a family outing. It was essential to the family. They needed their own common beach history.” But the family is quickly thrown off the beach by the American woman who now owns the land. Her servant threatens to call the police: “All you didn’t see the chain?” he asks. “That mean don’t come in. It don’t mean you are welcome.”

All across the Virgin Islands, Americans are purchasing beachfront that was once public property, asserting their geographic as well as cultural dominance over the Virgin Islands. This, we see, is the danger of allowing Virgin Islands voices to be silenced. Without their beaches, Yanique’s characters are robbed of the places at which they feel most at home. The old wives mourn the loss of these essential gathering places:

The beaches were for everyone. They are our community parks. Our zoos. Our arboretums. Our places to marry and make love. But the beaches would be filthy with all the people. The bodies oozing sunscreen, the wrappers left behind. Was there nothing good left in the world for us, for them, for me?

One of the main pleasures of the novel is watching Yanique’s characters fight back and challenge stereotypes. Soon after the incident on the American woman’s beach, Anette’s family helps lead a protest against such owners. When they decide to hold the protest on the same beach at which the movie was filmed, we understand that they’re writing a new Virgin Islands story, one that pushes back against a legacy of exploitation. This is also Anette’s project in becoming a history teacher. “History is a kind of magic I doing here,” Anette says, and her refusal to conform to standard American English emphasizes her fierce independence.

Yanique’s language is another one of the joys of reading this novel. Although Anette embraces the language of her homeland, Eeona resists it: “Speak proper English,” Eeona reprimands her sister. Anette’s sections of the novel are heavily influenced by Virgin Islands Creole, while Eeona is scrupulous about adhering to American English grammar. The tension between these two narrative voices serves as a reminder of the larger cultural tensions that make up the novel’s core. Yanique’s accomplishment here lies in giving us both sides of the story, showing us both the dominant American narratives and the Virgin Islands narratives that undermine them.

This is not just any magical realist story, and it’s certainly not a second-rate imitation of García Márquez. This is a Virgin Islands story, and Yanqiue has succeeded beautifully in emerging from the grand tradition of magical realism and creating something entirely new.

Sophie Murguia is Editor in Chief of The Amherst Student.