Curated by KEI LIM

If you’re looking for a book to wrap your year’s reading, look no further! December recommendations from Issue 30 contributors A.J. BERMUDEZ and CASEY WALKER and Managing Editor EMILY EVERETT think back to old favorites and old memories.

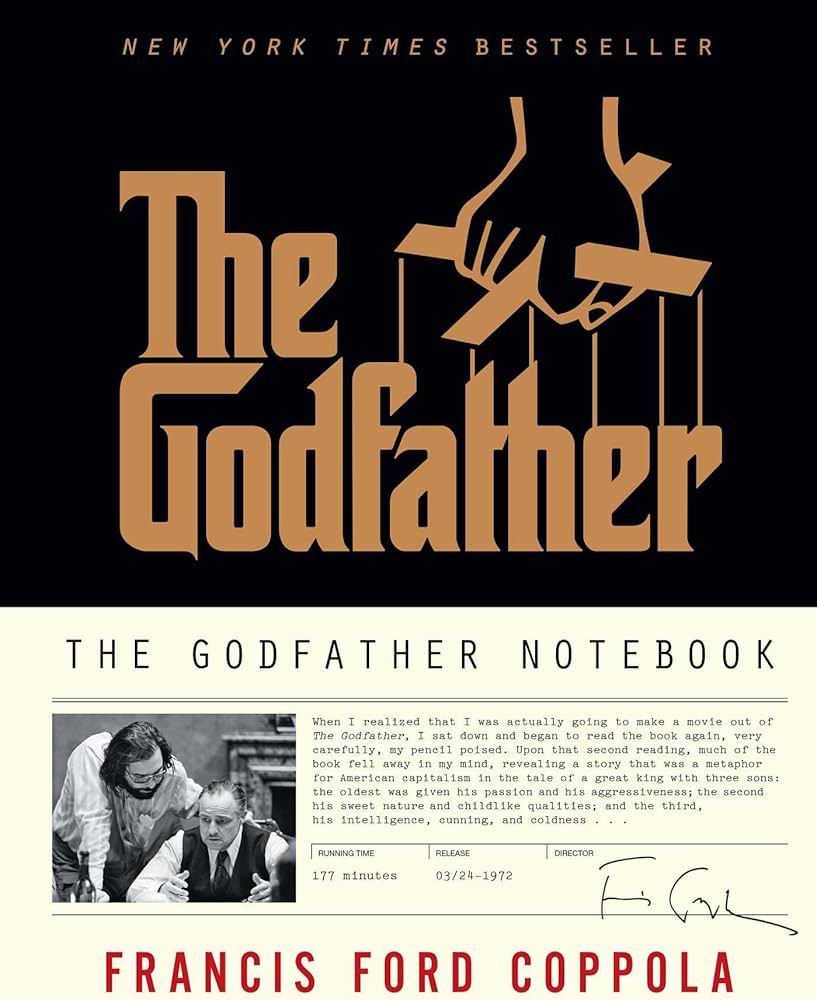

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Notebook, recommended by Issue 30 Contributor A. J. Bermudez

When I was a little girl and my classmates were all hung up on Charlotte’s Web, my favorite book was The Godfather. It was a weird choice––the book is rife with problematic elements, and I wasn’t exactly the target demo (unless one could predict my forthcoming career writing books and movies)––but I loved it. It was expansive, emotive, richly textured, vividly written, and downright awesome.

To this day, I’m grateful to the small-town librarians who let me check it out, again and again, when I could barely see over the counter. And I’m grateful to my present-day big-city librarians, with whom I chat about books, movies, and recently my latest literary squeeze: The Godfather Notebook.

This 784-page tome is, in one sense, a very impressive coffee table book. In another, arguably truer sense, it’s an in-depth artifact of the literary notion of palimpsest. Modeled after the “prompt books” endemic to stage managing (Coppola picked up the form during his early theater arts training), the notebook features each individual page of the original book (razor-cut and pasted onto larger pages) with the margins then meticulously populated by scribbled notes, timestamps, and the like.

Coppola called the notebook a “multilayered roadmap,” and it is just that: a conglomeration of charts, maps, drawings, photos, scene and page numbers, strike-throughs, question marks, typewriter smears, and handwritten notes in multiple colors (often on top of one another). It is, at its crux, a sort of geological cross-section––an overlay of ideas, of meanings, of media. It’s a book about a film about a book about fictional narratives inspired by nonfictional narratives informed by journalism, photography, memoir, theater, history, and curation.

The book is, incidentally, rife with good ideas for writers, irrespective of medium. At the beginning of each section, Coppola lays out five areas of consideration: (1) synopsis [what literally happens, plot-wise]; (2) the times [setting, worldbuilding, prevailing values, et al.]; (3) imagery and tone [vibes]; (4) the core [what a particular scene is really about]; and (5) pitfalls [relatable flags, at least for me, regarding sentimentality, momentum, and the like].

As a kid, around the time I was holed up reading The Godfather, I was, perhaps unshockingly, kind of a loner. It wasn’t until years later that I’d realize the best work is formed not in isolation but in community. This goes for books, films, books turned into films, music, theater, visual art, cross-disciplinary experimentation, and (as far as I can tell) just about everything else.

As intimate as it is informative, The Godfather Notebook is evidence of story-building as intrinsically collaborative. I recommend it to anyone who likes to take things apart and put them back together; to anyone who harbors a secret love of bad handwriting; and to anyone who, like a true critic, is poised to be as horrified by my literary tastes as my third-grade teacher. Ultimately, it’s a reminder that books are often how weird loners like me (and maybe you) find each other.

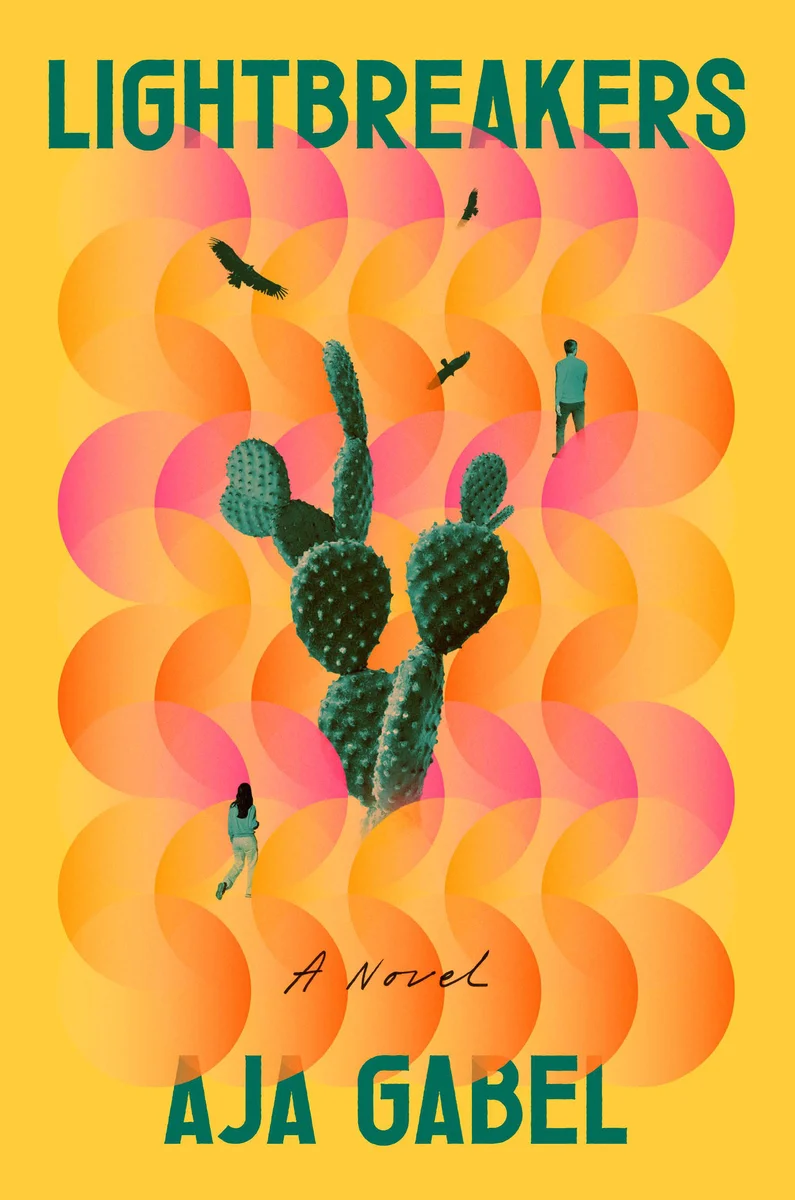

Aja Gabel’s Lightbreakers, recommended by Managing Editor Emily Everett

The best books are the ones you have to wait for. Aja Gabel’s 2018 debut novel, a look behind the curtain into the world of top-tier classical musicians, showcased her talent for sitting in complex relationships without trying to solve or simplify them. Seven years later, her new novel Lightbreakers takes that to the next level—letting the marriage and grief at the heart of the story ebb and flow in ways that feel nuanced and natural, not in service of a clean narrative structure. It’s also a treat to pull back the curtain on two more unusual worlds; the main characters, husband and wife Noah and Maya, work in quantum physics and modern art, respectively. The central hook of the book is a heartbreaking thought experiment—what if you could travel years back into your memories and change the outcome—that (happily for me) feels less like time-travel and more like an excavation of how memory and mourning operate, and how loss can both bind people together and drive them apart. I have never read an accounting of grief that makes room for so much messiness—all the ungenerous things we do to ourselves, and to other people, in that state, and all the ugly and odd and inconsequential things we latch onto in order to make a story we can understand, a story that explains the loss and somehow holds it. There’s a lot at work in Lightbreakers, big moves and big concepts, and Gabel pulls off every one. But I know it’s the novel’s quieter questions I’ll be thinking about the longest.

Charles Portis’ Gringos, recommended by Issue 30 Contributor Casey Walker

Every year when winter comes, and the days are short and dark, I get the first lines of Charles Portis’s novel, Gringos, stuck in my head:

Christmas again in Yucatán. Another year gone by and I was still scratching around this limestone peninsula. I woke at eight, late for me, wondering where I might find something to eat. Once again there had been no scramble among the hostesses of Mérida to see who could get me for Christmas dinner. Would the Astro Café be open? The Cocina Económica? The Express? I couldn’t remember from one holiday to the next about these things. A wasp, I saw, was building a nest under my window sill. It was a gray blossom on a stem. Go off for a few days and nature starts creeping back into your little clearing.

The great spiritual weariness here is immaculate but, importantly, it’s funny—Christmas dinner at the Astro Cafe and, again, I wasn’t even invited.

Portis is best known for his novel True Grit, and its various movie adaptations, but he also wrote four other novels, two of which are among my very favorites—The Dog of the South and Gringos. Both books are about Americans on shaky ground venturing headlong into Mexico, where they encounter all manner of other Americans of their rough type—petty cons, loquacious weirdos, and autodidact philosophers. Portis’s characters seldom have dreams any bigger than winning back a beloved stolen automobile or making a small living trafficking on the disreputable side of the antiquities trade (though, really, is there a reputable trade in cultural artifacts?). And yet, even the most modest plan in a Portis novel is subject to ruin—life is figured as a rather endless series of kicked over sandcastles.

There’s a weary sense in Portis’s books that maybe we could accept the wreckage caused by waves and tides—at least, there’s no use complaining about a nature beyond human control—but there remains a real gall in dealing with the bullies and brutes who come stomping through whatever small things we do manage to build.

But don’t misunderstand: these are funny books, not cynical ones, and they are tight and propulsive, not sagging or perambulatory. There’s always a dignity to continuing to pursue your errands, however fruitless. You meet a lot of oddballs along the way, for one. Very often, Portis will seem like he’s building you up to a big writerly thought about life, only to deflate it: “You put things off and then one morning you wake up and say—today I will change the oil in my truck.”

I think a lot about that wasp under the window sill at the end of the first paragraph of Gringos. “It was a gray blossom on a stem,” Portis writes. “Go off for a few days and nature starts creeping back into your little clearing.”

Those lines are Portis, perfectly distilled. Crisp description bending into a cosmic metaphor without doing much more than describing exactly what the narrator sees out his window. There’s a statement of principles here: you’re going to work as hard as you can to make your little place, your little clearing, and despite it all, the world outside your window is always coming to fill it all in again. This doesn’t mean quit, but it does mean don’t be surprised by the wasps.