The year is 1972, and as you’re driving along the highway in Rifle, Colorado, a giant orange curtain appears, looming vibrantly over a distant valley. Or, maybe it’s 1997 and you’re in Switzerland. You’ve decided it’s a nice day for a walk in Berrower Park when you notice there’s something different about the trees—namely that they’re covered in gargantuan sheets of polyester fabric.

These scenes describe just two of artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s most famous (and well documented) works. Others include “The Umbrellas”—where the couple simultaneously installed blue umbrellas in Japan and yellow umbrellas in California—and, more recently, “The Gates,” where saffron-colored panels were hung from vinyl gates across a 23-mile stretch of Central Park. In part because of the large scale of their works, the duo’s activity has always generated controversy, and their current project, “Over the River,” is no exception.

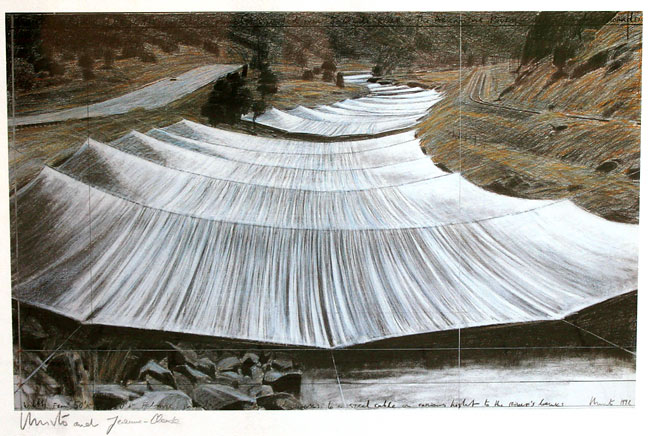

Like all Jeanne-Claude–Christo productions, “Over the River” is a temporary installation. The project, conceived by the pair in 1992, entails suspending 5.9 miles of shiny, transparent fabric panels above the Arkansas River in south-central Colorado for two weeks. The objective is to provide two unique perspectives of the area: one offers a distinct view of the sky to rafters and boaters while the other offers motorists and highway goers a beautiful reflection of the heavens.

While the artists have assured opponents of the project that no harm will come to Colorado’s waterways, canyons, or wildlife, various environmental groups remain skeptical. Their concerns target not only the disruption caused during construction and viewing periods, but also the aftereffects of such a project—an estimated 9,100 steel anchors will permanently remain embedded in canyon walls, and the structure’s disassembly is projected to take two years.

Apart from environmental criticisms, naysayers also pose economic concerns. Eco-tourism is one of the area’s biggest industries, and many businesses fear that lane closures and heavy traffic caused by construction will have adverse effects on income. Again, Christo (Jeanne-Claude passed away in 2009) guarantees no great economic disturbance. He promises to work during the off-seasons and expects to attract more tourists to the area with his installation.

The question is: how much can we put at risk for the sake of art? Can we justify approving a project with such potentially unfavorable effects? For some answers, you might look to the heated debate surrounding the National Geographic Spotlight. Most think “Over the River” is a waste of resources that says nothing and harms the environment. Others think the project is successful because it draws attention to the area and bolsters a desire to conserve it. Is this endeavor worth its anticipated environmental and economic repercussions? Or are those “repercussions” nothing more than hyperbolic criticisms of a shot at creating beauty?

To access images and information related to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s past artwork, click here. For more information on “Over the River,” visit the project’s official website here.